The stage musical “New York, New York” is part travelogue of that city and part recreation of great scenes from “On the Town,” “Wonderful Town” and a slew of MGM movies from the early 1950s. It is also, at times, something far more significant.

“New York, New York” indicts the musical entertainment business of the city for its discrimination against minorities and immigrants, the very artists who had already transformed the American sound even before World War II. In other words, this sort-of-new musical “inspired” by Earl M. Rauch’s screenplay for Martin Scorsese’s 1977 classic starring Robert De Niro and Liza Minnelli is something of a mixed bag.

Its love letter to the city often doesn’t set well on its target board of the city, especially in the confused first act. But “New York, New York,” under the savvy direction and choreography of Susan Stroman and featuring a score by John Kander and the late Fred Ebb, additional lyrics by Lin-Manuel Miranda and a book by David Thompson and Sharon Washington, ultimately delivers its melting-pot message with intelligence, style and, yes, good old-fashioned razzle-dazzle.

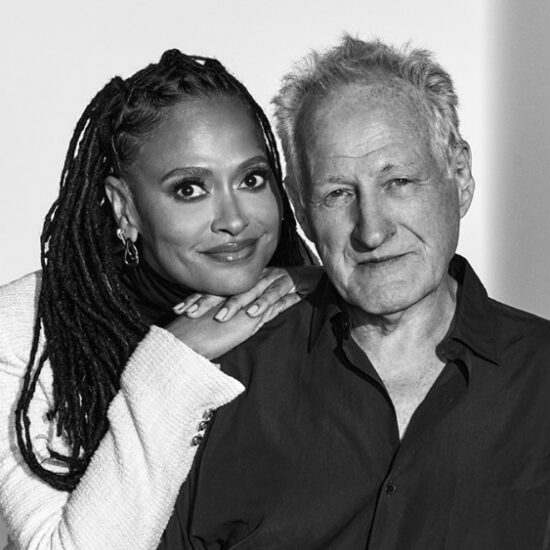

Most wonderful, Kander has found a real soulmate in Miranda, their new songs the silver lining that shines through some awkward missteps elsewhere. Kander and Ebb’s classic title song and “But the World Goes ‘Round” from the Scorsese movie continue to pack a wallop, but Miranda’s poetry brings out the composer’s more introspective, lyrical side. Unfortunately, “new” songs by Kander and Ebb often give the show a dated rinky-dink sound and should have been left in the trunk.

And that’s not all that needs cutting.

One thing any book writer should have learned watching the original film is that jazz saxophonist Jimmy Doyle’s relentless pursuit of the pop singer Francine Evans tests more than just her patience — it tests ours. Many of their early scenes together in the movie come off as improvisation on Valium.

There’s nothing wrong with two characters, even if they’re terribly mismatched, from falling in love fast simply because they want to screw. Rodgers and Hammerstein invented the conditional love song so that Billy Bigelow and Julie Jordan in “Carousel” could kick start their romance in record time with “If I Loved You.” When the two meet in “New York,” Billy and Julie don’t declare their love. (That would have been too corny, even for 1945.) Billy and Julie declare their mutual lust and what would happen if they fell in love sometime in the future. (That’s sophisticated, even today.)

This new “New York, New York” is set in 1946, but according to current musical theater dictates, the heroine must be independent above all else. (Even Aaron Sorkin’s new interpretation of Guenevere in “Camelot” turns her into a feminist firebrand, despite Lerner and Loewe giving the character songs that exemplify her innate frivolousness.) Playing Jimmy, Colton Ryan possesses somewhat more finesse than De Niro in his pursuit of the girl; but playing Francine Evans, Anna Uzele has a lot less grace than Minnelli in rejecting the boy. This Francine doesn’t need a man. She needs a manager to promote her in the boxing ring.

About 45 minutes into the show, Jimmy, who’s Irish-American, and Francine, who’s Black, do fall in love (finally) with “I Love Music,” one of those generic “new” songs by Kander and Ebb. Jimmy sings and plays a number of musical instruments that he collects and stores in his apartment. Is this guy starting his own band or opening a pawn shop? The flimsy song is in no way romance-inducing. (Suffice to say that one of the instruments played is a tuba.)

Jimmy and Francine’s story is just one of many told in “New York, New York.” There’s also a Polish-Jewish violinist (Oliver Prose) who wants to go to Juilliard; a Black jazz trumpeter (John Clay III) who wants to stop washing dishes for a living; a gay Cuban drummer (Angel Sigala) who wants his father to stop calling him “maricon”; and a Black cleaning woman (Allison Blackwell) who wants to sing at the Met. This sounds like a narrative mess, but since each of these stories has essentially the same goal — to make it in New York City — Thompson and Washington’s book handles all the many success sagas with surprising efficiency. Best of all, Kander and Miranda’s songs for these characters’ respective paths to fame and fortune are poignant and rousing. Especially heartbreaking is the number “Gold,” sung with genuine pathos by Emily Skinner in the role of the reluctant violin teacher.

Meanwhile, the first act remains a problem because of Jimmy and Francine’s long-gestating romance and one senseless show-stopper: In “Wine and Peaches” (another “new” one by Kander and Ebb), Jimmy visits his construction worker friends on the umpteenth floor of an unfinished skyscraper so they can all tap dance there. (Beowulf Boritt’s scenic design throughout the show is breathtaking.) But to what effect? Why is anybody dancing to this terrible music? Shouldn’t Jimmy be below on 10th Avenue pursuing his career and/or Francine?

It’s unfortunate that Kander and Miranda did not reprise or write new numbers with lyrics for this show’s many musical interludes: “New York in the Rain” and “New York in the Snow” merely glue the story together as Stroman’s dancers leisurely cross the stage in one kind of storm after another. What’s needed is material that doesn’t banish the major characters from the stage but brings them together, such as the “Johanna” reprise from “Sweeney Todd” or the “Tonight” reprise from “West Side Story.”

“New York, New York” also features songs from Kander and Ebb’s trunk of flops. Those include “Let’s Hear It for Me,” originally sung by Barbra Streisand in “Funny Lady,” and “Quiet Thing,” originally sung by Minnelli in “Flora, the Red Menace.” While they’re not classics, both songs fit well into this new story. Ryan’s mezza-voce and pianissimo in the Minnelli standard are stunning in today’s world of blasting, oversold vocals.

And when Jimmy and Francine finally do fall in love for a couple of minutes, frankly, we have to take them at their word. The second act comes together not with their romance but when he achieves his dream to have his own band (it features the supporting characters played by Sigala and Clay). Jimmy’s “making it” forces all the stories to coalesce. It helps, too, that Stroman’s choreography explodes when her characters can dance to robust band music.

“But the World Goes ‘Round” and “New York, New York” are saved for the end, and Uzele achieves the remarkable feat of not making you wish Minnelli were singing instead. Sandwiched in between those standards is Kander and Miranda’s most luminous moment. It’s simply titled “Light,” and while the song doesn’t further the plot — it could easily be excised — the moment embodies the show’s bright optimism when the cast fills Boritt’s city street to witness the Streethenge that takes place four times a year in Manhattan, even back in 1946. Ken Billington’s lighting design offers up a rainbow of colors that descend right into the auditorium.

Scorsese’s movie ends on a melancholic note with two ex-lovers who decide, at the last moment, not to keep their appointment to see each other. Much less sophisticated, this new stage musical delivers a loud and happy ending. It’s the music of “Light,” however, that lingers long after the razzle-dazzle of that famous title song has stopped buzzing in your ears.