The thing about “open secrets” is: everyone knows what the secret is, but no one wants to acknowledge or talk about it. Not really, at least — if somebody’s peers and colleagues are all privy to some forbidden or socially unacceptable facts, and bringing it up forces them to reckon with some complicated feelings, then hey, why do we need to bring any of that up? For years, it was more or less an open secret within the comedy community that Louis C.K. had done things and said things that made female comedians feel uncomfortable. Lines were crossed. People were left traumatized and/or disillusioned. Because of his kingmaker position within both the stand-up and the sitcom worlds, people were afraid to speak out; women who did speak up were marginalized, blackballed, or treated like they’d committed some sort of treason.

All of these allegations were steadfastly denied, at least in public, by C.K. Then came the 2017 New York Times article, and his admission that “these stories are true.” He said that he was going to step back and take some time to listen. Nine months later, he was trying out new material. You remember what happened next.

Sorry/Not Sorry, a documentary by filmmakers Caroline Suh and Cara Mones made in conjunction with The New York Times, revisits the incidents, the blind-item pieces and accusations, the aftermath and the eventual comeback of C.K. Mostly, though, it wants to ask a few questions, such as: Why, exactly, were these accusations suppressed and ridiculed for so long, even before his TV show Louis and his later specials turned him into a figurehead? What was it about this particular open secret that allowed it to be just an open, unexamined “secret?” And while the comic suffered mild financial losses and public shaming for his bad behavior, why was his so-called “cancellation” so brief as to be practically nonexistent?

If you have potential answers to these queries, in fact, the people behind this documentary would probably love to hear from you, as they don’t pretend to have the answers. Or any new insights, to be honest. That’s only one of the issues that hampers this attempt to dig back into both this specific case study and the larger social conditions that caused others’ complicity and his calling-out in the first place. Another would be a matter of timing. Sorry/Not Sorry comes at a moment that, years after an arc has been established, a real examination of the who, what, where, and why is nothing short of a necessity.

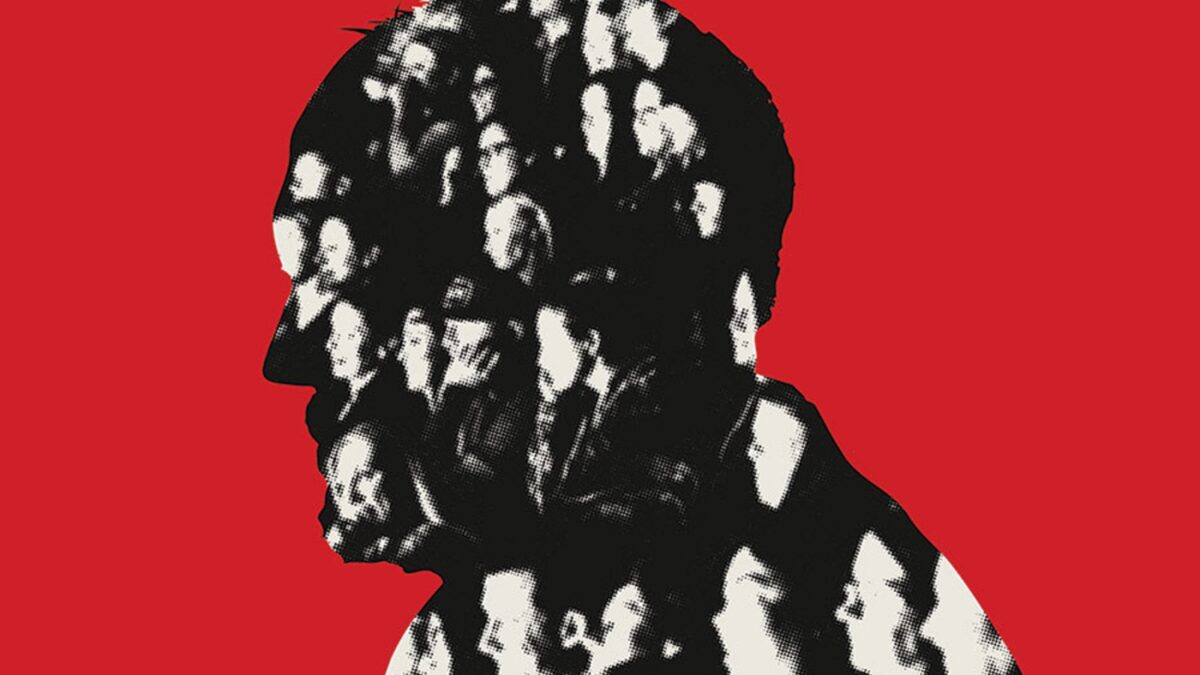

Louis C.K. presents onstage during the 88th Annual Academy Awards at the Dolby Theatre on February 28, 2016, in Hollywood, California.

Getty Images

But it also finds itself in the unenviable position of being so removed from that ground-zero outing that, per the filmmakers, many of the women who were willing to speak out then are no longer compelled to do so now. Nothing’s changed, so why risk another backlash again? And it’s close enough to C.K.’s resurgence that virtually no one from the comedy world, with one major exception, would participate either. Every major comic was asked, Suh admitted in a Q&A after the film’s premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival Sunday night. Everyone declined. (Including, it should probably go without saying, C.K. himself.)

There are still a decent amount of talking heads in Sorry/Not Sorry, ranging from showrunner Michael Schur (who cast Louis in Parks & Recreation, then brought him back for a guest spot even after he’d heard the rumors) to Michael Ian Black (who, ah, wrote a tweet) to the three New York Times reporters who wrote the article. You get a lot of smart cultural critics — Wesley Morris, Alison Herman, Jesse David Fox — weighing in on C.K.’s career and the warning signs in his bits as well. The abundant omissions of who’s M.I.A. in terms of interviewees start to become glaring after a while, however, and the result sometimes feels like you’re watching the equivalent of a write-around. Topics such as the power structure that enabled such behavior to go unpunished (notably C.K.’s powerful manager Dave Becky) while victims suffered consequences, and how that morphed over his career as he became more famous, feel frustratingly underserved. Ditto the immediate response after companies like FX severed ties with C.K. The clips from his routines, TV appearances, and podcast exchanges do a lot of heavy lifting. If you like seeing montages of headlines, you’ll meet more than your daily recommended requirement.

To be fair, those who do sit for long interviews provide a lot of damning evidence for the prosecution and fill in a lot of blanks. Especially Jen Kirkman, a stand-up who spent a lot of time with C.K. early in her career and recounts a car ride through old haunts in Boston that somehow becomes oddly sexualized. An incident in a club after a show led to her mentioning on her podcast how an unnamed pervy comic is well-known for masturbating in front of women, which — unnamed or not — still led to Kirkman catching a lot of shit from all corners. Like a lot of us who were curious to see if/how he’d ever address this in his work, she was disappointed to see that his response was a defensive recasting of his harassment as a kink and any hint of remorse was AWOL. Her acquaintance with C.K. spans several eras of his career as well as her own, which allows for a timeline that connects a hell of a lot of dots.

There are also extended segments centered around Abby Schachner, one of the women who spoke about how she allegedly heard C.K. masturbating while speaking to her over the phone for the Times, and Megan Koester, a writer who asked attendees at the Just For Laughs comedy festival about his behavior and was screamed at by one of the fest’s executives. The inclusion of their voices, their stories, their anger, their refusal to be solely defined by their association with his misconduct and their determination to still express themselves outside of the industry provide a personal aspect to what’s become a pored-over, debated-to-death topic that still has zero resolution in sight. Power is still abused and problematic artists still can’t be separated from the art. “People ask, ‘Where do you draw the line?’” Schur notes, before saying, “I don’t know, but lines have to be drawn somewhere.”

Suh admitted that as a big fan of C.K.’s work and “a member of Generation X,” she found her own reaction to the scandal to be contradictory and confusing, and that a big reason for wanting to make the film was to untangle her own feelings about all of this. (It’s also why she approached a younger filmmaker like Mones to collaborate, as a way of checking and balancing what seemed “normal” to her then versus now.) That sense of uncertainty carries over into the doc itself. The fact that it’s forcing us to return to a conversation that has not been finished is enough to justify its existence. Sorry/Not Sorry needs to do more than just jog our memory. It needs to be a lot clearer about where its own lines are drawn and why this is where ours should be drawn as well.