E

VE HEWSON WILL NOT be doing karaoke today. “I have to be really, really hammered to do karaoke,” the actress explains, walking through New York’s Central Park. “I would really have to be a whole bottle of tequila deep.” Not that she is opposed to such things (“I mean, I am Irish”), but it’s 10 a.m. on a Wednesday, and up until very, very recently, sober public singing — or sober singing of any kind, really — was a complete nonstarter. “Absolutely not,” she says. “Hard no. It was absolutely my biggest fear.”

So she’d played a non-singing nurse in The Knick, a non-singing prostitute in The Luminaries, and a non-singing murderer in Bad Sisters. Then she’d taken a sleeping pill on a flight to London, read the script to Flora and Son — about a struggling single mom who finds a guitar and a way to forge a relationship with her teenage son — found it to be a “slam dunk,” and decided not to “shit my pants,” as she usually does at the thought of playing a chanteuse, but instead to call her agent and make a case for why John Carney, the writer-director of Once, should give her the main role: “I said, ‘I can give you something that sounds like a real person trying to express themselves, rather than someone who is trained or has a natural gift.’ I think it was the sleeping pill. I was kind of like, ‘I’m just gonna have to put my big-girl panties on and learn how to fucking sing.’”

Which she did, flying to L.A. and spending the next few months in musical boot camp, not with her dad — who just so happens to be Paul Hewson, a.k.a. Bono — but rather with Eric Vetro. “He does Ariana Grande, Scarlett Johansson, and everyone who sings in a movie,” Hewson tells me. “He basically became my therapist.” She also brushed up on guitar, courtesy of Yousician. Then she reached out to Carney to ask for the film’s songs so that she could start practicing them, only to learn that … there weren’t any songs to practice — yet. “I’m like, ‘What the fuck? We’re supposed to be shooting next week!’ And he’s like, ‘Yeah, yeah, no, we’re gonna go to the studio this weekend, and you and I are going to try and come up with something.’”

By this point in the conversation, Hewson and I have found our way over to the track around the Central Park reservoir, which is exactly where she was first seen in a film. “I was sitting right here, with New York in the background,” she says of her appearance in a short movie her tutor shot while the family was tagging along with U2’s tour, as they did each summer. “I didn’t have any lines. I just sat there. But — I don’t know — I felt just completely comfortable with the camera.” Legend has it that the director of photography was so moved that he cried.

Hewson’s parents, Bono and activist Ali Hewson, were less moved, and made it perfectly clear that a career in the arts wasn’t recommended for any of their four children. There were the summers on tour, sure, seeing the world and glomming on to the rock-star lifestyle. But the rest of the year was explicitly designed to be a counterpoint to that for the Hewson clan. They went to church on Sundays. She attended her local primary school. When it came to secondary school, Hewson schlepped it on public transport. “There would be the odd fucking teenage dickhead that would sing ‘It’s a Beautiful Day’ at me on the train, and I’d just be like, ‘Um, OK.’ But Irish people have a really good sense of humor. We take the piss out of each other every five seconds.”

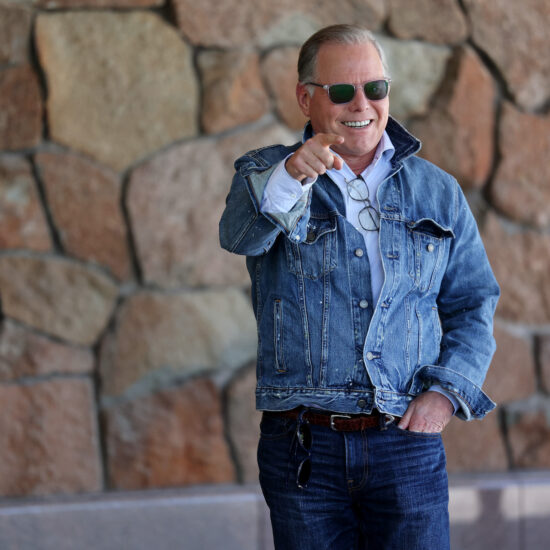

Eve Hewson and Bono attend The (RED) Nightcap at Goals House to celebrate the partners and people that have made it possible for (RED) to deliver more than $700 million to the fight against AIDS and Covid, helping more than 245 million people.

Monica Schipper/Getty Images for (RED)

Growing up, Hewson, 32, ran with a “big motley crew” who were often the children of friends her parents met in middle school, before U2 was even the foggiest idea. “There wasn’t much going on,” she says of their sleepy Dublin suburb. “So we reenacted the Kylie Minogue and Robbie Williams music videos. We’d put a coin in a bowl of flour and try and get it out with our hands behind our back.” On Wednesdays, Hewson would get together with a local theater troupe and perform Monty Python scenes. There was a period when “the most fun thing to do” was rent a bunch of movies, watch them on repeat, and then prank call people. Sometimes they would pull numbers from her dad’s contact list. Sometimes they would prank call Justin Timberlake.

At 15, Hewson’s tutor cast her in a feature film. “And that was the kicker,” she says. “That was the moment I was committed.” She spent a summer studying at the New York Film Academy. She got accepted into the prestigious Tisch acting program at NYU. She moved to New York and “would walk up Sixth Avenue in my all-black attire, smoking cigarettes and chugging coffee, reciting my monologues in my head, feeling like a true thespian.” When her parents voiced concerns, she pushed back on the pushback. “My dad’s dad told him not to sing, so I kind of threw that back in his face,” she says.

Then again, there have been times when being who she is, both physically and metaphysically, has been a bit of a mindfuck in an industry known for fucking with minds. “I have grown up with people having an idea of who I am before I’ve even met them,” she says. “Way before I walk into the room, people have decided whether they like me or they don’t, and that’s a strong thing to consistently have growing up. And it’s also hard to talk about because then people are like, ‘Oh, she’s complaining about her privilege.’”

Which, to be clear, she isn’t. She’s just trying to explain that, maybe more than the average person, she’s had to question every single time whether an offer was “real” or only being offered “because, you know, they wanted the headline of Bono’s daughter being in it,” she says, dropping her voice low when she says “Bono’s daughter.” When she auditioned for The Knick, the casting director submitted just her first name (“like I was Madonna or something”). She doesn’t know who told director Steven Soderbergh whose kid she was. “But I think when he found out, he was like, ‘OK, I have to meet her,’ because obviously he thought I would be some head wreck,” she says wryly. “We have bad PR as a collective nepo-baby group. We need a new PR team. It’s hard out there for the nepo babies.”

It’s probably a testament to her solidity — and her Irish penchant for taking the piss — that when New York magazine published its nepo-baby cover story last year, Hewson dove headlong into the fray. “Actually pretty devastated i’m not featured in the nepo baby article like haven’t they seen my hit show Bad Sisters??? The NERVE,” she tweeted, after having commented on the article with one single word: “jealous.” She was surprised by the overwhelming response to what she had thought was her obviously underwhelming one. “I tweet stupid shit all day long. No one’s paid attention,” she tells me. “And then all of a sudden it became this huge debate and people were chiming in all these different opinions, and, oh, my God, it was just madness. But it was great promotion for Bad Sisters. I mean, the internet is a dark place, but you gotta use these things to your advantage.”

Certainly, Hewson is not entitled enough to be confused as to why there should be hubbub around her entitlement. She was in the car with her dad and Bobby Shriver when they came up with the idea for Red. She traveled to Cork to meet the orphans arriving from Belarus as part of her mom’s work with the Chernobyl Children’s Project. When it came to Flora, she knew that there would be those who would question her right to play such a hardscrabble character. “Three days before we started shooting, I almost quit,” she tells me. “I was sick with anxiety about it. The conversation that’s happening right now about privilege? I understand where it’s coming from. I take it seriously.”

Hewson explains that despite her privilege, she’s endured her fair share of harrowing Hollywood experiences, including a #MeToo episode that caused her to almost quit acting. “Honestly, if I get into it, then I have to call my therapist,” she says, declining to name the film. Afterward, she found herself having panic attacks before auditions, and wondering if her body was sabotaging her acting career as a form of self-preservation. A year later, the #MeToo movement happened, bringing with it more interesting roles for women, including Hewson’s in The Luminaries — “it was similar to what I was going through in my head because she was sort of the object of everyone’s desire, and she felt trapped” — and a sense of empowerment that helped her fall in love with acting again. “All of a sudden, people were listening to women. They had access to the media, and social media, and they were able to say, ‘This has been my experience. You have to listen to me now.’ And that has changed everything on any set. If I have an issue, they better fucking take me seriously. They have to.”

Orén Kinlan and Eve Hewson in ‘Flora and Son.’

Apple TV+

If there were any remaining questions about whether Hewson should be taken seriously on her own merits (and there likely weren’t), they were put to rest with Flora, when the premiere at Sundance received a standing ovation. For her own part, Hewson has come to terms with the fact that her privilege helped jump-start her career, but that it could not possibly be all that has sustained it. “I asked myself a lot of questions, but what I came down to was that I am an actor,” she says. “We are playing characters that are unlike ourselves. The actual craft of it is to not know anything about this person’s life or their context or their background, and to find a way in to find empathy to then create a true authentic version of that person. I have played prostitutes before. I have played murderers. I have played a man living inside of a woman’s body. I’ve been able to astral project myself and other human beings, you know? I have to just remember what I do.”

Plus, it turned out that in some ways, there couldn’t have been a better fit for Flora than Hewson. The movie’s best song is one that she helped write — a skill for which she is more than happy to credit her lineage. “I grew up songwriting,” she says, explaining how her dad sometimes had her cut words from a newspaper and use them to create lyrics, Mad Libs-style. “I mean, we were so involved in his work every day. There was music being played, and, ‘What do you think of this song? Do you like this verse?’ Like, my dad didn’t teach me how to ride a bike. He taught me how to write a song.” The one she sings with co-star Joseph Gordon-Levitt was written in a Dublin studio in just eight hours and recorded that very night.

Now, with Flora set to be released theatrically on Sep. 22 (and by Apple TV+ Sept. 29), Hewson has just returned from Cape Cod, where she’d been working on Netflix’s murder-mystery series The Perfect Couple until production was shut down by WGA picketers (“I mean, look, I get what they’re doing”). Next, she’ll head to the U.K. to film Hedda, based on Ibsen’s play. Immediately after that, she’ll film Season Two of Bad Sisters. Her schedule is so packed and peripatetic that, she tells me, while she’d love a boyfriend, the prospect feels logistically impossible. “I did start a Hinge account,” says Hewson. “The first person that I got matched with is an 85-year-old man. His name was Malcolm. He worked in radio. And he was just looking for an attractive, young, slimmer lady to go on adventures with” — she makes air quotes — “‘when safe, of course.’”

Speaking of safety, a couple of bikers ride past, and Hewson cocks her head to one side. “You know, I still don’t know how to ride a bike,” she admits. Then she sees the plotting look on my face and bursts out laughing: “No fucking way.”

Production Credits

Hair by ANTHONY CAMPBELL at A-FRAME. Makeup by BRIGITTE REISS-ANDERSEN at A-FRAME. Styling by KATE YOUNG at THE WALL GROUP. Styling Assistance by SEAN NGUYEN. Dress and Cardigan by DRIES VAN NOTEN. Earrings by BOTTEGA VENETA.