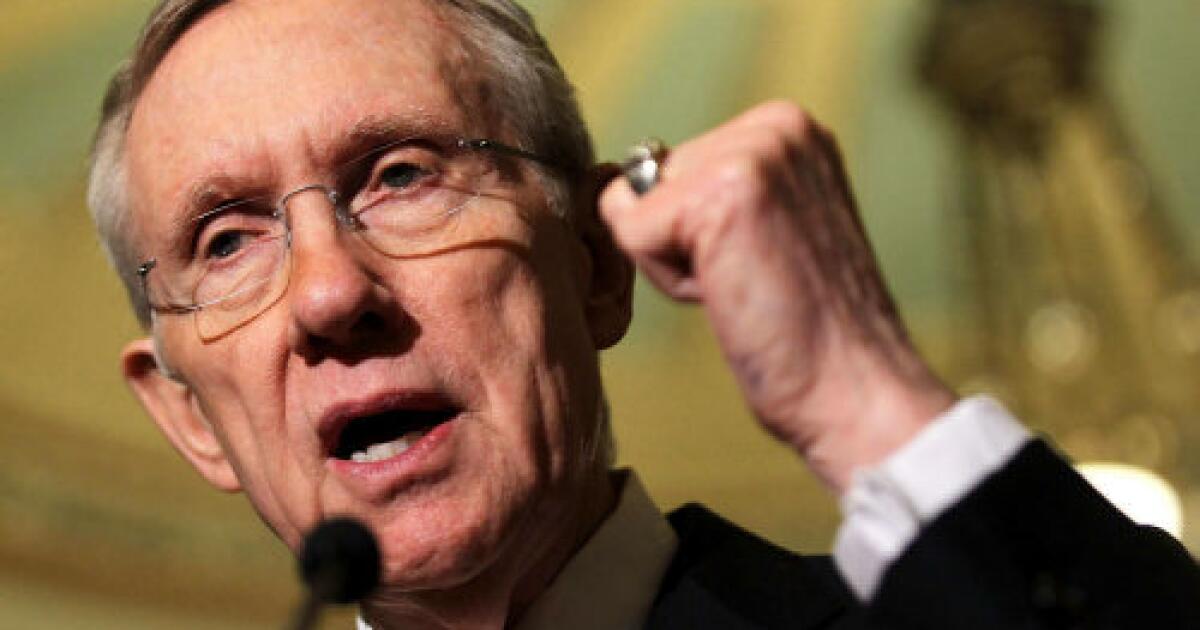

Harry Reid had a hard life that took him from poverty in the Nevada desert to the height of power on Capitol Hill. Along the way, he could reliably count on one thing: tough election fights.

He lost one U.S. Senate contest by 624 votes. He won another by less than .01%.

“I should have lost that race,” Reid told Jon Ralston, author of an upcoming biography, after being reelected to the Senate in 1998 by just 401 votes.

He vowed never to let that happen again.

And so Reid, cunning and ruthless in equal measure, leveraged his enormous clout and fundraising muscle to turn Nevada’s creaky state party into a campaign juggernaut.

He not only won a fourth term in 2004, but prevailed after another brutal campaign six years later. In the process, Reid pushed Nevada to the fore of the presidential nominating process and helped turn the state from reliably red to a purplish shade of blue.

Nevada remains a campaign battleground and will be hotly contested again in 2024. But Democrats start with an edge after winning every presidential election here since 2008. They had lost eight of the previous 10.

That tilt away from the Republican Party is part of a sweeping political makeover of the West, from the Pacific Coast to the Rocky Mountains, that has turned much of the former GOP stronghold into Democratic turf.

In this series, “The New West,” I’m looking at the reasons behind the two-decade-long shift, which has redrawn the national political map and scrambled the race for the White House.

Part of the shift is due to the GOP’s sharp rightward turn, which has alienated many younger, independent and suburban voters who prefer a more broad-minded, less harshly judgmental attitude, especially on social issues.

Some of it is from demographic changes: the relocation of left-leaning Californians to places like Nevada and the growth and increased clout of Democratic-leaning Latinos and other nonwhite voters.

Some of it can be attributed to determined individuals.

In California it was President Clinton, who sought to ensure his 1996 reelection by lavishing the state with time and attention.

In Nevada it was Reid — arguably the most powerful elected official in the state’s history — who died nearly two years ago but whose handiwork continues to shape its political landscape.

He had a crucial ally in the Culinary Union, which represents the workers who keep the state’s fun-and-frolic industries up and running — and regularly musters one of the most skilled and effective voter turnout operations in the country.

The Las Vegas Culinary Union canvasses door-to-door to encourage voter turnout, including early in the pandemic for the 2020 election.

(Mark Z. Barabak / Los Angeles Times)

For months before an election, hundreds of paid door-knockers work eight to nine hours a day, six days a week, persisting even when temperatures crawl past a cruel 110 degrees.

Good luck finding very many others willing to do that.

In 1994, Democrats suffered a wipeout of cataclysmic proportions.

The party lost 54 House seats nationwide and eight in the Senate, giving Republicans unified control of Congress for the first time in more than 40 years. In Nevada, Democrats lost a congressman and surrendered control of the state Assembly.

“All of us were reeling,” recalled Barbara Buckley, a Democrat who was first elected to Nevada’s Assembly that year.

It was clear, she said, where blame lay: “Us. … We were losing.”

Nevada Democrats were “not coordinated, not organized, not coalesced, not talking about issues people care[d] about,” Buckley said.

Meetings were convened. Many meetings over many years that included assorted Democratic politicians and their allies.

“There was this realization that there needed to be more organization, more coordination,” said Buckley, who went on to represent the Las Vegas area for 10 years and become Nevada’s first female Assembly speaker. “Everyone needed to up their game.”

Reid was among those participating in the postmortems, his interest and engagement growing considerably after his 1998 political near-death experience.

A big part of the problem was the state party, which, as Ralston describes it, was more of a “kaffeeklatsch” for reminiscing old-timers than a serious campaign organization. So Reid seized control, recruiting experienced hands to professionalize operations, find out where Nevada’s likely Democratic voters lived and make sure they turned out.

One of his most important hires was Rebecca Lambe, a savvy veteran of Missouri politics, who arrived at party headquarters in Las Vegas in 2003 to find a receptionist, an intern, a scattering of cardboard boxes and some beat-up furniture.

She led the party’s rebuilding from the ground up.

“It was organizing,” Lambe, who became Reid’s political right hand, said on a recent oven-hot afternoon. “It was voter registration. It was data. It was opposition research. It was the gamut.”

In 2007, Democrats gained an enormous advantage after the party took control of the Senate and Reid became majority leader. He brought a new, Western perspective to the role, and instantly became one of the most formidable lawmakers — and prolific fundraisers — in Washington.

From then on, the state party and its ambitious revamping work never wanted for cash.

Years earlier, Reid had chosen Steven Horsford, head of the Culinary Union’s job training program, to serve on the Democratic National Committee. That put the senator’s proxy in a key position when the party looked to shake things up.

Iowa and New Hampshire — two overwhelmingly white, heavily rural states — had long dominated the presidential selection process by voting first. Democrats decided to broaden the competition, starting in 2008, by revamping their political calendar.

Several Western states bid to hold early caucuses after Iowa’s. South Carolina, which has a large Black population, was awarded a primary to follow New Hampshire’s.

Horsford helped make Nevada’s case.

“We made the argument … [based on] the diversity of the people here,” said Horsford, now a Las Vegas congressman and head of the Congressional Black Caucus, also citing “the ability to do true retail politics, the growing labor movement and the fact that it’s not an expensive media market.”

Nevada beat out Arizona and Colorado, among other states, to claim the early slot. (It “didn’t hurt any,” said Howard Dean, national party chairman at the time, that the Senate’s top Democrat called the state home.)

Once Nevada prevailed, Reid made it his personal mission to ensure the caucuses ran smoothly — not just to avoid embarrassment, but also as part of his party-building strategy.

(Republicans moved up their caucuses to coincide with the Democratic balloting, but the GOP contests didn’t draw nearly as much voter interest or attention from candidates.)

Jim Manley, a top congressional aide to Reid at the time, remembers the senator devoting long hours to “hectoring, phone calls, public pressure” to see that the party’s large field of presidential hopefuls came to Nevada early and often, energizing Democrats.

“But it wasn’t just brute strength or manipulation,” Manley said. “It was making the case that Nevada” — with its burgeoning minority population and growing union membership — “was a rising state, trending Democratic.”

A steady stream of presidential contestants campaigned in Nevada ahead of the party’s 2008 caucuses, which drew wide national notice but ended in a muddle. Hillary Clinton topped the vote tally. However, when delegates were apportioned, Barack Obama finished with the most.

The undisputed winner was Reid.

Turnout for the Democratic caucuses exceeded expectation, topping 117,000 participants. (In 2004, fewer than 10,000 people bothered showing up.)

Better still, from Reid’s perspective: On caucus day alone, his party registered 30,000 new voters.

D. Taylor, head of the Culinary Union’s parent, UNITE HERE, remembers being at one of the earlier meetings with Reid and despairing Democrats.

Seated recently in his cramped office at the Culinary Union’s scruffy headquarters just off the Las Vegas Strip, Taylor recalls telling them, “The last people you need to talk to are people like me.”

Culinary Union Local 226, based just off the Las Vegas Strip, has become a powerhouse in Nevada politics, benefiting workers and Democrats.

(Mark Z. Barabak / Los Angeles Times)

Nevada was changing, rapidly. The population was exploding — the state has gained more than 1 million people since the latest turn of the century — and the percentages of Black, Latino, Asian American and Pacific Islander residents were soaring as well.

Taylor could see it in the ranks of the Culinary Union.

Founded in 1935, it had helped recruit the workforce that turned Las Vegas into the internationally renowned gambling and tourist mecca we now know (albeit one that remained segregated into the 1960s). Today, the union’s roughly 60,000 members come from nearly 200 countries; just about half are immigrants.

Turning Nevada’s abundant newcomers into Democrats and moving them to the polls was essential to Reid’s operation and vital to the state’s political conversion.

The Culinary Union became an indispensable part of the turnout effort. And crucial to its success were the peer-to-peer relationships that members forged in their respective communities.

“People came out of the hotels — guest room attendants, banquet servers, bartenders” — and went door-to-door, said Maggie Carlton, a former coffee shop server who canvassed for the Culinary Union before she was elected in 1998, with the union’s strong support, to the state Senate.

Labor leader D. Taylor with then-President Obama in the back of a group photo that Obama signed with thanks to the Vegas Culinary Union. Taylor was among the union activists who worked with Harry Reid to build support for Democrats among newcomers to Nevada.

(Mark Z. Barabak / Los Angeles Times)

“We get it,” said Carlton, who went on to became the state’s longest-serving female lawmaker before term limits ended her time in office in 2022. “We’re talking to our friends and families. A lot of them may be people they work right alongside when they’re in the hotel.”

Horsford suggests that he never would have been elected but for the union’s backing and the way its troops approach elections — without emphasizing party or a particular candidate.

“That’s not what motivates their members,” Horsford said. “It’s, ‘Go vote for this issue. Healthcare. Immigration. Better education or jobs. And, oh, this is where this person stands and why we support them.’”

Reid, deeply respected and widely reviled — hence those numerous hard-fought elections — left a lasting mark on his home state.

He delivered a fortune in federal funding and blocked creation of a nuclear waste dump at Yucca Mountain, less than 100 miles from Las Vegas.

Reid shaped Nevada politics like few others. Now that he’s departed, Republicans hope to end Democrats’ presidential win streak, starting next year.

But there’s no forgetting him.

When candidates fly to Las Vegas to campaign, they touch down just off the Strip, its fantasia skyline in clear view, at Harry Reid International Airport.