Quiet storm began as a radio format.

In the 1970s, a style of music emerged in popularity on the late-night radio airwaves – one which celebrated slow tempos, punctuated with soulful, intimate vocals. The radio format – dubbed quiet storm – showcased many of the era’s most versatile performers, linking songs through emotion and sensuality. Named after a 1975 Smokey Robinson album, the radio genre grew from a combination of influences.

For many, the sounds of this genre captured something beyond soul, including a more personal or spiritual element.

Among quiet storm’s featured artists include Smokey Robinson, Marvin Gaye, Al Green, Stevie Wonder, Sade and Roberta Flack.

“Seamlessly updating the style of contemplative romantic soul music [Smokey Robinson had] invented with “You’ve Really Got a Hold On Me”, “Ooo Baby Baby”, “The Tracks of My Tears”, and “More Love”, . . . ‘A Quiet Storm’ plays like a concept album devoted to tranquil monogamy,” writes Eric Harvey for Pitchfork.

Strings, spacious arrangements and softness are features you might find in the quiet storm repertoire. Soul music was re-connecting closer with spirituals and no artist fits more within this crossroad than Roberta Flack, whose voice was heralded for its velvety texture and gospel roots.

Where did quiet storm come from?

Quiet storm was born at WHUR 96.3 – Howard University’s contemporary radio station – when intern Melvin Lindsey would serve as substitute DJ one evening in 1976.

His programming of uninterrupted moody, slow tempo soul and R&B music was an instant success with listeners. Lindsey became a regular DJ for the station and others began adopting similar themes for their own interpretations of the format:

“You didn’t even have to have a radio in D.C. All you had to do is open the window. You couldn’t help but hear ‘the quiet storm.’ That’s how popular it was. It was the air that D.C. breathed,” said Donnie Simpson, host of “The Donnie Simpson Morning Show.”

Is quiet storm a genre?

Quiet storm is difficult to categorize, sometimes referred to as a “supergenre.” The songs framed within this label span across pop, R&B, soul, jazz and jazz fusion – the unifying characteristics often described as ‘easy-flowing’ or ‘romantic.’ Author Jason King writes, “quiet storm might be best considered a racialized take on– or redefinition of– ambient music.”

On the complication of defining the genre, Eric Harvey explains:

“The duplicability of the quiet storm format is what separates it from a traditional genre of music. If genres are communicative forces that bind songs, artists, and albums together, then radio formats are an especially commercialized, top-down breed. . .Quiet storm appropriates R&B and soul “slow jams” and recontextualizes them into rotations with their peers and predecessors. An artist might only have one ballad on an album, but to quiet storm listeners it might be the only track they hear. Artists and labels quickly picked up on this.”

As the radio format grew in popularity, what defined quiet storm began to broaden, including older material and new music written to fit within its spirit. However, quiet storm faced criticism for its apolitical nature and softness, while others contested it uniquely celebrated the Black experience.

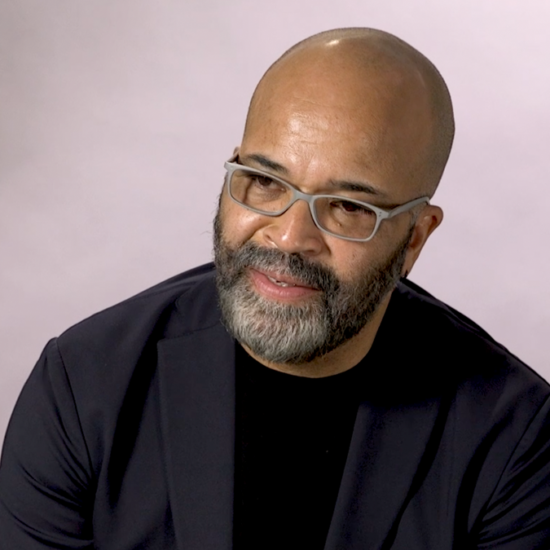

Roberta Flack, quiet storm and her album “Quiet Fire” —

As Jason King describes it, “the distinctive magic of Roberta Flack is inextricably related to the minimalist quietude of her classic ballads.” Though many of her ballads topped the charts, Roberta Flack’s third studio album, “Quiet Fire,” was released in 1971 to less critical acclaim than her previous work. However, in recent years the album has found renewed appreciation and its gospel-inspired tracks fit perfectly within the quiet storm canon.

To UMass Professor H. Zahra Caldwell, “‘Quiet Fire’ does not refer to the album’s title track; rather, it signals the mood, music and Flack’s artistry.” She says:

“The album, like Flack herself, has a complex position in the annals of music history. Flack’s biography aligns, in many ways, with the narrative of ‘Quiet Fire’. . . .there were those who saw her music as too middle-of-the-road, too AM radio, too subdued and lacking the earmarks of soul expected of Black singers. . .”

To these critiques, Roberta Flack herself would ague that she shouldn’t have to fit into any one category:

“I know what I am and I don’t want to, and I shouldn’t have to, change in order be who I am.”

Work Cited