4K RESTORATION IN THEATERS! The opening shot of György Fehér’s Twilight is not unlike the opening shot of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining—both are aerial perspectives that pan over vast stretches of woodland. But whereas Kubrick’s camera moved with an anxious, supernatural haste, indicative of what’s to come, Twilight reveals itself as slow, cruel, and almost nauseatingly vertiginous.

I mention The Shining because there are several seminal films that will justifiably be considered when trying to classify Twilight. Kubrick is enough of a lofty comparison, but add to that rank the likes of Andrei Tarkovsky with Stalker and Béla Tarr with Satan’s Tango, and hidden somewhere amongst them lies Twilight—a dark, thoroughly unflinching vision with a manner all its own.

Twilight follows a retired police inspector (Péter Haumann) who searches a rural community for the murderer of a schoolgirl found dead in the woods. The film—although made in 1990—had gone unseen for some time, almost a phantasm in its own right. Its recent 4k restoration uses the original 35mm camera negative as well as the original magnetic sound tapes. To finish the resurrection, Twilight’s color grading was overseen by the film’s cinematographer Miklós Gurbán.

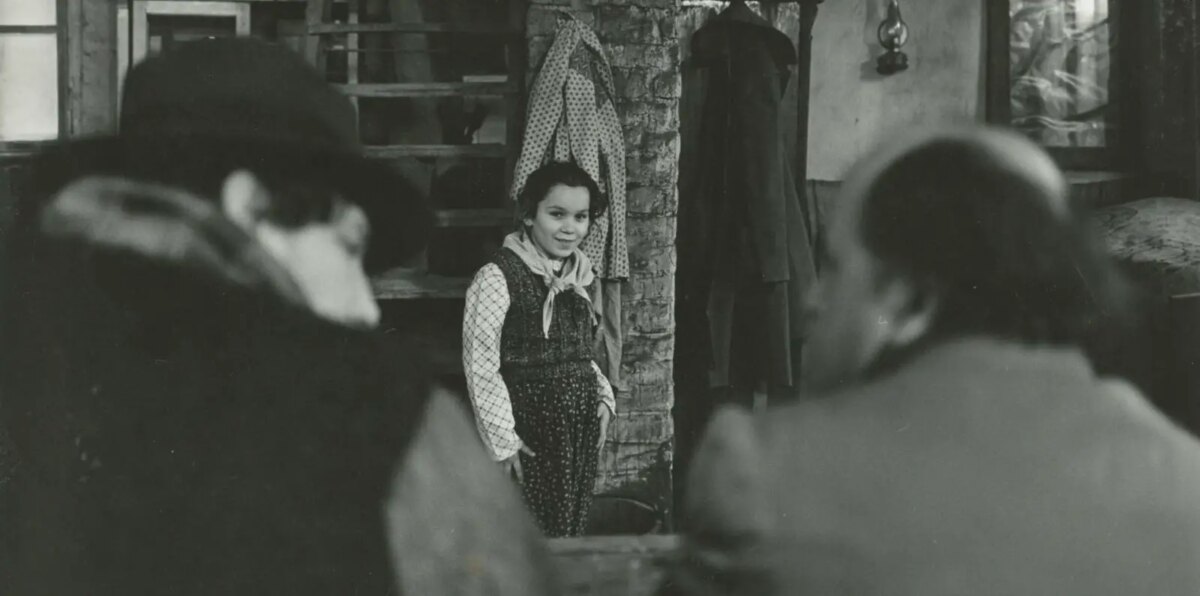

“…retired police inspector who searches…for the murderer of a schoolgirl.”..

The result is a staggering visual aesthetic. The black-and-white cinematography captures the landscape with visceral articulation. Most locations are wrapped in an undulating fog that mimics reality—images that begin as opaque open up and evolve as though beckoning the audience as their eyes adjust. Further, Twilight’s shots are long and utterly unhurried, affording the film a hypnotic effect. To multiply this sensation, the camera is regularly either too far away from characters to lend them any pathos or so close that it feels claustrophobic. The starkness of Twilight’s conception is matched only by its desolateness.

It is on this visual foundation Fehér that constructs layers of suggestion. The dialogue is stripped down to a bare skeleton, and events carry on as if simultaneously of utmost importance and of no meaning at all. The funerary audio design only amplifies the unsettlingly naked tone. However, Twilight’s sacrifice of substantive occurrence is not so much lost as returned to its visuals, which take on a spirit of their own. Many ideas are not spoken but displayed and left for interpretation. It is a world of provocative conflict, not unlike the Zone in Stalker—a world where the inspector, and thus, the audience, feels unable to escape, but also a world that suggests the discovery of profound meaning, if only one can bear it long enough. It is a burden but also a delight of nuanced storytelling.

Ultimately, since György Fehér only directed two feature films during his life, comparisons between Twilight and its forebears (as well as progeny) might be misguided. And yet, it is an assured film, mature in its own right and poignant in its ruminations on madness, obsession, and futility; it knows the precise story it wants to tell and tells it with surgical precision. With Twilight, Fehér does not reach the heights of his colleagues, but he certainly proves his place among them.