In a time of war, laughter — even of the wryest kind — can feel like an unpardonable luxury. And if Ukrainian director Antonio Lukich’s delightfully droll “Luxembourg Luxembourg” were even a little more flippant, and didn’t cut its comedic antics with an equal dose of melancholic wisdom, perhaps there would be some guilt attached to enjoying it so much. But with his second feature, an expansion of ambition after his wonkily wistful debut, “My Thoughts Are Silent,” Lukich hasn’t just made a slice of much-needed escapism. In the sincerity of its sentimentality and its humane, universal observations around absent fathers, errant sons and estranged brothers, the movie not only earns us the right to laugh during a period of suffering and conflict, it makes sharing in the warmth of its sweet-natured humor seem like a vital, revivifying act of resistance.

There’s a scuzzy-Scorsese vibe to the film’s propulsive, boisterous ’90s-set opening as Kolya and Vasya (Adrian and Damian Suleiman), identical twin boys getting into trouble the way boys do, scramble around the train yards of Lubny, the central Ukrainian city they call home. As nostalgically narrated by an older if little wiser Kolya, the events of this particular day are instructive as to the boys’ relationship. When the freight train they’re kicking about in unexpectedly begins to move, Vasya jumps off just in time, while the more fearful Kolya clings to the boxcar helplessly, watching his brother recede to a forlorn far-off figure on the tracks. Kolya will be rescued in amusingly OTT style by his gangster father stopping the train at gunpoint while Boney M’s “Daddy Cool” blasts over the soundtrack. But the differences in the boys’ natures is set. Vasya is seemingly destined for an easier life because as narrator Kolya observes mournfully, “They say that when a son looks like his mother, he is born happy. Even though we are twins, Vasya looks like our mother; I look like our dad.”

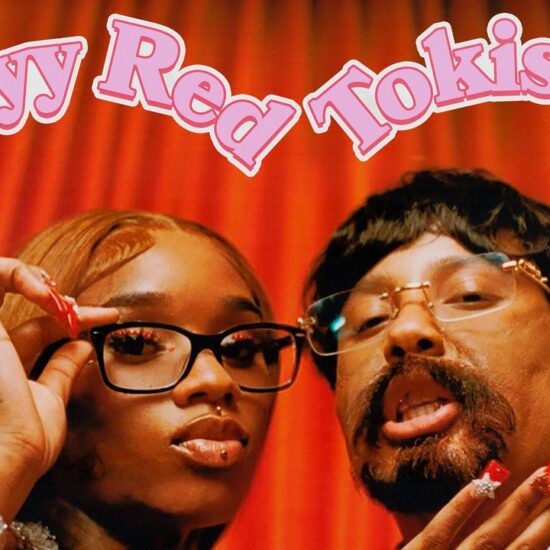

Twenty years later, with their father long gone from the scene and now mostly the subject of Kolya’s hero-worship mythologizing, the schism between Kolya and Vasya (played as adults with lovely hangdog panache by Ukrainian rappers Amil and Ramil Nasirov) has only grown wider. Kolya is a scrappy, low-level drug dealer whose unreliability and surly demeanor at his day job as a bus driver gets him demoted to the “worst” route, used almost exclusively by pensioners — and he only avoids being fired altogether through the forbearance of the stepfather/boss he despises. Vasya, meanwhile, is in law enforcement, hopeful of a promotion and married to pretty if spoiled Masha (Karina Cherchevych), who has just had the couple’s first child. Each brother seems embarrassed by the other, which is perhaps why they rarely talk anymore. But then Kolya gets a phone call from a consulate official to tell him that their father, whom Kolya mostly, adoringly, remembers as an imposing silhouette or a tattooed hand on a steering wheel, is dying in a hospital in Luxembourg. Some kind of reluctant reunion is surely in the cards.

But one of the welcome eccentricities of Lukich’s film is that it takes its time getting there, where a more schematic version of this story would have the brothers’ bickering and bonding be the whole thrust of the plot. Lukich’s screenplay is partially inspired by his own experience of parental absence, and perhaps that’s why it is as much invested in establishing the brothers’ separate lives in Lubny — where their outlooks are oppositional yet equally shaped by their dad’s abandonment — as it is with effecting some sort of genre-mandated reconciliation. From this more generous, character-focused perspective, a lot of the film’s comedy emerges. DP Misha Lubarsky’s deadpan framing gives the Nasirov brothers the look of silent-comedy stonefaces and makes witty little sight gags out of the slightest moments: Vasya, failing a lie detector test when he’s asked about his criminal connections; Kolya, suspended in a swimming pool in a spinal-corrective brace, or stacking books up on a chair to compensate for his short stature when getting a passport photo taken.

This delayed-gratification approach also means we get to see how Kolya is perhaps not all bad, especially through his thawing relationship with Larysa Petrivna (a great, irascible turn from the late Lyudmyla Sachenko), the elderly bus passenger he injures through negligence and then must work for to pay off the debt. And as we learn of Vasya’s difficult relationship with his wealthy in-laws, and the condescension of his bosses at work, it appears his reputation for having his act together might be just as shakily founded as Kolya’s for being an irredeemable screw-up. So when in the final third, the brothers finally embark on their road trip to Luxembourg (a country chosen, one suspects, because like the boys’ father, it remains something of a mystery to outsiders, defined mostly in the popular imagination as a kind of landlocked limbo between better-known neighbors), the payoff is subtle but surprisingly heartfelt. “Luxembourg, Luxembourg” can by no stretch be read as a commentary on Ukraine’s current, bitter struggle for survival. But it is a beautifully modulated, funny and compassionate product of an irreverence that is just as much part of the national character as its resilience in the face of adversity and as such, a gentle reminder — not of the fight but of what’s worth fighting for.