John Hoogenakker has made quite a name for himself.

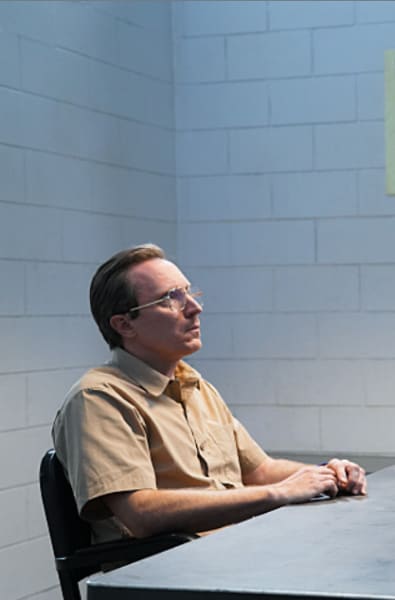

From television (Dopesick) to film and commercials, you’ve seen his face or heard his voice in various eclectic roles. And his career continues to ascend, with his stunning portrayal of real-life Branch Davidian Clive Doyle in the Showtime miniseries Waco: The Aftermath.

The series covers both the immediate aftermath of the Waco standoff and takes a look into the past, bridging multiple storylines into a captivating and moving series that does as much to teach us about the lessons of history as it does to help us understand the present.

We were fortunate enough to speak with the illuminating Hoogenakker, who was sincere and incredibly nuanced in his responses to our questions about the series.

We could have chatted with him all day. Enjoy this thoughtful conversation with the delightful Hoogenakker.

Why did you feel it important to show Clive’s early days with David Koresh in conjunction with the present-day trial?

Well, because I’m fascinated by what grabs a person and pulls them into a situation like Clive found himself in. And even after the standoff until he passed away, which turns out was, I think, the day after we wrapped principal photography, he continued to believe that Koresh was the reincarnation of God and continued to lead Bible study groups.

As a father, he gave both of his young daughter’s hands in marriage to Koresh. I am fascinated by other people’s worldviews, particularly when they’re so far removed from my own. Getting to study that and sitting down at the table with that is fascinating to me.

That’s the buildup, obviously, that this idea of this guy immigrating from Australia with his mom when he is in his early twenties back in the mid-sixties. The Branch Davidian compound outside of Waco at Mount Carmel went back decades, and he had been a Seventh-Day Adventist.

They were at a church meeting in Australia, and they heard that there was going to be a Bible study group with this other group, and they went and studied with that other group. When word got back to their Seventh-Day Adventist church that they had actually sat down with this other group, they were excommunicated from their church.

So, this whole odyssey begins, ending with him and his mother waiting for the call to take that huge trip from Australia to the middle of Texas and live as part of this community. That gets him into the community and then the trial afterward.

But to your question, I think the reason it’s important to go back and kind of look at how he got to where he ended up is that he just represents a microcosm of this tribalization that’s going on in this country.

By looking at one person’s journey in micro, maybe when we zoom back out and look at how these other people ended up, where they ended up.

Then by extension, how white supremacists seized on the standoffs at Waco and Ruby Ridge to kind of try and recruit members and feed their party line that the government is out to get you, we can then maybe start to understand how we got to things like Charlottesville and January 6.

How familiar were you with the events of Waco prior to landing the role?

I’ve got to think. I was 15, turning 16 when it happened. So, it was on TV. Of course, in the early nineties, basically, you had three or four flavors of network television news to watch, and they were all kind of like, which anchorman do you want to listen to? But it’s all kind of the same storyline.

I remembered the way that it was presented to us back then vaguely. During the pandemic, my wife and I, like everybody else, were casting around for something to watch, and we landed on season one and burned through it pretty quickly.

I thought it was fascinating. I like ambiguity and depiction of characters, particularly ones that are historical figures, because I think it’s seldom that everything is completely black and white.

What I learned before doing a deep dive after landing the role was that the ATF, the FBI, and the Hostage Rescue Team were occasionally working at odds with one another.

There wasn’t really a general on the ground in charge of the campaign, and the Branch Davidians, led by David Koresh, set themselves on a collision course with the far greater force that had a lot of skin in the game.

What drew you to the role?

Clive was the one Branch Davidian who stood trial for the murder of four federal agents subsequent to the standoff and was fully acquitted. He served time up until that verdict came down, and then he was released.

He testified before Congress, and he allowed the defense to paint a more human and approachable face onto a group of people who were super ultra-orthodox hardcore and had been portrayed as completely insane in the news. I was interested in that. I was interested in learning more about his perspective.

It’s still a source of deep division and argument as to who started the fires.

Many of the Branch Davidians still claim, the ones still alive, that it was absolutely the federal government. Whereas the federal government claims they had recordings of Branch Davidians inside the compound planning where to start fires if their walls were ever breached.

Clive claims he never held a gun, and his defense attorney was able to get him off because, presumably, the jury couldn’t believe that this mild-mannered guy ever would’ve held a gun. First of all, they don’t really recognize the rules that you and I follow as the most important rules, which puts them at odds with a lot of people.

I wanted to try and understand how a parent could hand their child over in this way to another adult.

I can’t say that I fully understand it beyond saying that to this guy who essentially lived the life of a monk.

It would be like his highest religious leader, who is, he believes, the incarnation of the divine, choosing his children and saying, “We’re going to have children. Your children and I are going to make children who will sit in judgment at the end of days.”

If you can wrap your brain around that idea, you can start to understand Clive Doyle. The harder the person is to understand, the more interested I am in trying to portray them.

What is the most challenging thing about portraying a real-life character and real-life events on screen?

Particularly when there’s someone as divisive as Clive Doyle is by virtue of the fact that he was a Branch Davidian, it’s that you have to make a decision as to how much of other people’s commentary you allow into your work.

I think what a lot of us ended up doing was digging as deeply as we could into how these people saw themselves and going with that. Everyone is the hero of their own story. Everyone justifies their own actions.

Everyone believes that they’re acting with the best of intentions, particularly if you’re a member of an inner circle of a group like this who is certain that they’ve got it right and everybody else has it wrong.

I think it can be very challenging, particularly when the person exists in the public mind and when they are a divisive character.

But I think at the end of the day, you kind of have to try and go to how that person sees themselves because, to me, it’s more interesting than if I play a Branch Davidian the way everybody alive in 1993 watching the news remembers Branch Davidians.

I think it’s more entertaining and it’s more nuanced to have your preconceptions challenged.

Some of the most gripping moments, I think, from the miniseries are in some of those courtroom scenes. What were those like to film?

Well, they were great from the standpoint that a lot of my earlier years were spent doing theater.

It’s a very different art form to film and television in that, generally, when you’re doing a play, you’ll sit down with the rest of your cast for the first few days, if not the first entire week, to do what’s called table work where you go through the play line by line. You make sure everybody’s on the same page.

But it also serves to get to know everyone and make sure you all have a shared understanding of the play and what the words mean and flesh out what your subtext is and that kind of thing. Whereas in film and television, the actor, it’s assumed, has done all that work before they show up.

Sometimes you’ll have a conversation with a director before you go to shoot, but ideally, you have an opportunity to ask a few questions if you have a few questions prior to shooting so that you’re kind of just ready to rock when the cameras roll.

One of the coolest scenes that we got to shoot in the courtroom was one where I was really just a bystander. A lot of it was watching Giovanni and Mike Cassidy work. But there was one day when Mike Shannon was in the witness box, and Giovanni was cross-examining him, and it was a good long scene.

I want to say it was like a six- or seven-minute scene, and they had two cameras on Giovanni, and they gave him three passes at the scene. Then they turned around, got the cameras on Mike, and gave him three passes at the scene.

There was a short reset between each take, but we were all locked in for twenty minutes or so while they got each actor’s coverage.

The cool thing with both of those guys, who are awesome to work with –great guys — is just how they’re at the top of their game. They’re super well prepared, and they had not run the scene prior. They filmed the rehearsals, they were wonderful, and there were slightly nuanced changes every time they ran it.

When you do theater, a lot of people are like, “How do you do the same story every single day, eight times a week?”

Well, it’s like if you’re a skier, each time you go down the mountain, it’s slightly different. If you’re a white-water rafter, each time you hit the rapids, it’s slightly different. It’s the same river, but you get to play each time.

And these guys were doing a wonderful job.

Did your perspective or thoughts about the event change at all as you went through the process of filming the miniseries?

Yeah. I mean, honestly, Whitney, I can give you the arc from when I was 16 and what I remember thinking then to what I think now. At the time, I thought it was a tragedy. And I remember at the time Bill Clinton was the president and the government’s take on it was, and I’m paraphrasing what the president said at the time.

He said that it was a tragedy that those people caused their children to be killed, and I don’t see it that way now. I don’t see it that way at all. I think that the federal government, particularly the ATF, needed a made-for-TV spectacle.

They needed a win in the eyes of the American people because they had suffered a bloody nose at Ruby Ridge and were facing cutbacks in Congress.

You may remember this if you’ve seen documentaries about it or read about it. Local news outlets knew that the ATF was going in there that morning, and they got turned around on the way to Mount Carmel, and they pulled over a postal carrier on a rural route and asked them which way to get to the compound.

The postal worker was like, “Why do you need to go to the compound?” And they were like, “Well, the ATF is going to ring him.” And he was like, “Oh, I see. Well, the compound’s over that way.” And then he turned around and went straight to the compound because it turned out the postal carrier lived at the compound.

And he warned them that it was showtime, and an ATF informant that had been kind of getting in with the Branch Davidians immediately left and told the ATF at their watching station, which was half a mile down the road, “Our cover is blown. They know we’re coming.”

The ATF made the call to go ahead with it. Again, there were cameras there to watch the ATF be victorious in that moment.

Now, this is making no comment about whether or not the Branch Davidians were up to illegal things because, as it turns out, they very likely were, but because of the way things went down, the case wasn’t able to be prosecuted then it would’ve had it gone down a different way.

And then, when the FBI came in after four ATF agents were killed, that introduced a new aspect to the dynamic right there on the ground. Then the Hostage Rescue Team came in, and they had different goals. These government bodies were not acting in concert with one another. They were stepping on each other’s toes.

If you’re in the government or if you’re in law enforcement and someone kills one of your coworkers, they were eager for a reprisal, it seemed.

I feel like the other side of it is that the Branch Davidians had an apocalyptic theology. They believed that it was all going to end in fire, and they were kind of on record of saying this, and the federal government knew this.

Then there was another aspect where they gave a video camera to the Branch Davidians to record themselves thinking, “We’ll give them enough rope, and they’re going to hang themselves.” But then they passed the video camera and the footage back out, which actually humanized them in a way that didn’t really help the government’s story.

They kind of left that out when they went to Janet Reno and said, “We believe these guys are abusing children in there.”

So I feel like David Koresh committed suicide by cop and took eighty souls with him, and the government was over-eager to be used in that regard. They all look pretty bad.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this quote, which goes to Ip Man, who was Bruce Lee’s martial arts teacher, and he says, “Compassion is the soul of martial arts.”

So, the idea is that when you have far superior power and force and training, and you know you can inflict grievous harm on someone who is perhaps not in their right mind or might do themselves harm, it becomes your responsibility. Your foremost goal is to end the situation peacefully.

That was where the government was making headway. It was taking a really long time, but I think Gary Noesner got something like thirty people out, and they were right towards the end, and they pushed too hard.

The government does not approach these situations in the same way anymore because when people have extremist beliefs and you back them into a corner, they will make extreme choices. That’s one of the things that we all learned at Waco. I guess getting to play a part in sort of dramatizing that lesson was important to me too.

Why do you feel this is still an important story to tell in today’s landscape, and what do you hope the audience can take away from the series?

I don’t think that we have to agree on everything. I don’t think it’s realistic, but I think we need to expend a lot more time and energy in listening and trying to understand. Most people, I wouldn’t even say Americans, because a lot of countries throughout the world deal with the same kinds of division that we deal with in this country.

And I think that the closer you get to people you are told are bad, the more commonalities you see with those people and yourself. There’s something there.

That’s why I kind of keep wanting to go back to stories like this and reinvestigate them because it’s very easy for someone who has a passing interest in current events to be like, “Oh, wasn’t that crazy group of people that got themselves killed by the government?” And just write it off like that. There’s a whole lot more to it than that.

And the government, while it has made changes subsequent to this tragedy when a tragedy like this occurs, you don’t get to just put it on a shelf and forget about it. I think it’s part of our responsibility as citizens in this country to continue looking at the things we have not gotten right. It’s very important to mark our successes. Absolutely.

We need to be clear about the things that we have gotten right and the things that we have achieved, but we can’t, in celebrating our successes, lose sight of the things that we still have to work on. And this is a tough one because, really, it’s about compassion and empathy for people.

Branch Davidians are very easy to, for an average American, not have compassion or empathy for. I think a lot of where we are right now is we’re just losing the muscle to have compassion and empathy for people on what we perceive to be the other side of the spectrum from us or a little way down the spectrum even.

Whitney, when I was a kid, I lived in a part of North Carolina now, way up in the mountains, beautiful, beautiful area, very rural here. But it’s right near Asheville, which is a super cultural, awesome town. A lot going on in Asheville.

I drove up here with some dear friends when I was 16 or 17 years old, and one of them was a girl who had dark, dark skin and one of them was a boy whose dad was a retired GI, and his mom was Korean, so he was mixed race. Then there was me, and I had really long hair. And at the time, I wore rainbow suspenders.

Our car broke down on a rural highway here, and it was on a Sunday. At that point in the mid-nineties in western North Carolina, nobody worked on Sundays, and our coolant hose just blew on the side of the road. We pulled over, and the three of us, a poster for diversity, got out of our station wagon.

No sooner have we gotten out of the station wagon than the first car to pass us stops and asks if they could help us. And I was like 16, 17 years old.

I was like, “No, I think we’re good.” I had no idea what was wrong with this car and how messed up it was. So that person goes on. Two more cars stopped before we were finally like, “Yeah, I think we’re pretty much screwed here.”

This woman named Nancy Brown pulled over and stayed with us until she found a tow truck to tow us to a small engine repair of this guy way back up in the woods who fitted my dad’s station wagon with a lawnmower coolant hose and gave us coolant and refused to take any payment and just wanted us to remember.

We drove back down the mountain. We were a couple of hours later than our parents thought we were going to be, but they weren’t freaked out because it was the nineties, and you just assumed everybody was late.

And now we’re at a place where if you drive up the wrong driveway in the dark, there can be deadly consequences because of the stories that we’re telling ourselves about each other without taking the time to let the other person tell us their own story.

To me, that’s a story that exemplifies how far we’ve gotten apart from one another just in my lifetime. If my work can do a little bit to kind of sit us down at the table with one another, then I’m grateful.

You can watch Waco: The Aftermath on Paramount+ With Showtime.

***This interview has been edited for length and clarity.***

Whitney Evans is a staff writer for TV Fanatic. Follow her on Twitter.