If you’re of a certain vintage, you’ll remember how inflexibly tribal music fans used to be. If you were, say, an alternative kid, you wouldn’t dream of listening to anything the rock kids were. It just wasn’t done.

Admitting you liked the odd Black Sabbath or Van Halen song risked jeopardizing your relationship with the other alt kids. And because you were already known as someone who preferred Joy Division over Judas Priest, the rockers would have nothing to do with you. Might as well go die on an iceberg somewhere.

There are still silos among music fans, but they’re nowhere near as rigidly peer-reviewed and enforced. In fact, I can’t remember ever seeing this much fluidity when it comes to music preferences.

I started to notice this several years ago when I did some guest lecturing on Canadian music history at Toronto’s Humber College. To get a better idea of who I was talking to, I asked all the 20-somethings in the class to recite the last five songs they played on their phones. It was illuminating.

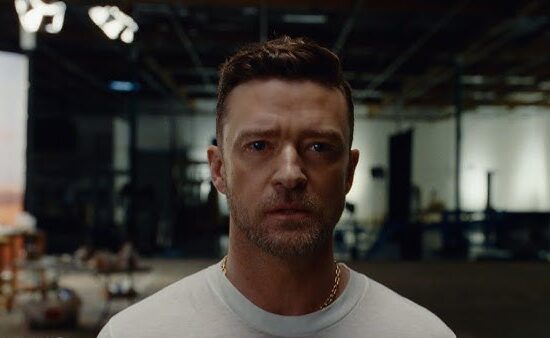

A typical playlist went like this: Drake, The Weeknd, AC/DC, Nicki Minaj, Led Zeppelin, Garth Brooks, Steve Aoki, the Beatles, Justin Bieber, The Cult, Arkells, Avicii. One male Humber student blew my mind when he said he was currently going through the discography of Billie Holiday — she died in 1959 — and the rest of the class nodded in approval.

When I betrayed my surprise with body language and a confused facial expression, the class wanted to know what was wrong. I tried to explain that in my day, we picked a lane and stuck with it. They looked at me like Bart regards Grandpa Simpson.

“Why compartmentalize music?” someone said. “If you do, you’re just limiting your options when it comes to finding your next favourite song.” I had to admit this kid had a point.

Since that day in class, I’ve been fascinated by the growing worthlessness of emphasizing musical genres. Speaking generally, the post-Napster streaming generation doesn’t want to be locked into one style of music or another. All they care about is great music, regardless of age, era, sound, scene or vintage. With a few pokes at their phones, they have access to more than 100 million songs for a price that can drop to free. Why wouldn’t they want to roam the musical universe?

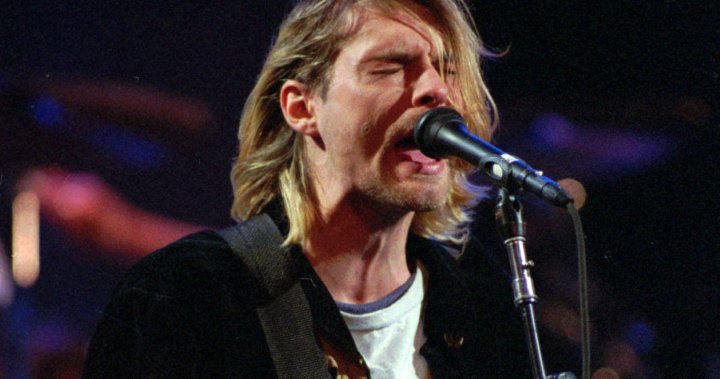

There’s another overlooked role of technology. An album like Nirvana’s Nevermind remains relevant more than 32 years after its release. Sure, we can talk about its evergreen punk rock and grunge aesthetics but focus on the age of the record and, if you can, try to remember what older music you were listening to then.

Would you have been listening to songs that were 32 years old? That would mean listening to mono recordings of post-Elvis-in-the-army/pre-Beatles music. It sounded old in 1991 and sounds even older today. Yet Nevermind still sounds like it could have been released last week. Some might say this points to the stagnation and ossification of rock, but I have a different take.

Starting in about 1969, newly equipped eight- and 16-track recording studio technology started to become available. Music got more complicated because it could, thanks to the magic of multi-tracking, overdubs and ever more sophisticated outboard processing gear.

Mono records had but disappeared and we began to get full-frequency high-fidelity stereo albums and singles. A properly recorded album — think Abbey Road — sounds contemporary as far as audio quality goes. Here Comes the Sun has sonic attributes every bit as good as something recorded yesterday. Songs more than 50 years old don’t sound it.

New data reinforces this. This is the time for Spotify Wrapped, the annual report card given to subscribers that summarizes all the songs they listened to over the last year. The company reports that users are more ecumenical than ever when it comes to their music consumption.

Instead of driving young streamers toward specific musical silos, genre tags — and Spotify has more than 6,000 of them (and growing) — are merely signs above an all-you-can-eat buffet that tells you something about what you might choose to eat.

Yes, yes, there are still musical tribes. We’ll never see the end of emo kids, goth followers and better-deal-than-mellow metal fans, but it wouldn’t surprise me to hear that even the current scenes with the strictest musical taste requirements offer far more latitude than what the original Lollapalooza generation had. (Speaking of which, have you seen the vast variety in Lollapalooza lineups over the last decade? I rest my case.)

And genres still matter. Music-based radio stations pick formats and carefully curate material from specific areas of music. For example, you’ll never hear Tool on a station that specializes in current pop. This is because a radio station makes a promise to its audience that every time they tune in, they will be rewarded with the type of music they expect from the station.

Want a different style of music? Hit the next preset. SiriusXM satellite radio is built on this pick-a-channel-for-specific-music approach. The difference is instead of bolting for a radio station operated by a rival company, SiriusXM can keep listeners in its very big sandbox by offering dozens of different music channels in one place.

The idea of radio formats has been in place for decades. This method of programming continues to work very well, but I believe there’s a large market for stations that cater to the tastes and musical whims of millennials and gen-Zers — which, come to think of it, would mean a return to an old-style Top 40. Those OG stations sampled from everywhere: pop, rock, R&B, country, dance — whatever the biggest songs on all the different charts. Maybe it’s time we returned to that.

Hey, it seems to be working for the older demos and their classic hits stations. Tune in to a Jack, a Boom, a Bob, or a Fresh, and you’ll hear a wide selection of oldies (sorry, but that’s what they are) that might offer a segue from the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive right into Livin’ on a Prayer from Bon Jovi.

Maybe it’s time we binned genres at least a little more. Like the kid in my class said, why limit yourself over labels? Respect all music, listen to what you want. Seems like the right thing to do, innit?