Ewan McGregor saw the strike coming in June, just as filming on his Paramount+ series A Gentleman in Moscow was nearing the finish line.

Like McGregor’s character, a Russian aristocrat under house arrest in a Soviet hotel, the shoot had nowhere to go. Continuing to film without a leading man was not an option, so McGregor, sporting a carefully clipped mustache, gathered colleagues to deliver the news many dreaded: the show would not go on.

Despite a brief reprieve as SAG-AFTRA extended talks with studios in early July, A Gentleman in Moscow eventually shut up shop last week. It had just seven days left to shoot. “He was gutted,” says someone in the room as McGregor gave a brief address to cast and crew.

A Gentleman in Moscow was not filming in the fulcrum of strike activity in Hollywood. Instead, it was one of a long line of shoots entrusted to the UK, a nation that has become a thriving £6.3B ($8.2B) production powerhouse on the foundations of generous tax breaks, a highly skilled workforce, and a shared language.

Shot at Manchester’s Space Studios, the eOne series was supporting a network of freelance crew in the north of England, all of whom now suddenly find themselves out of work, with little prospect of another major production pitching up in the neighborhood anytime soon.

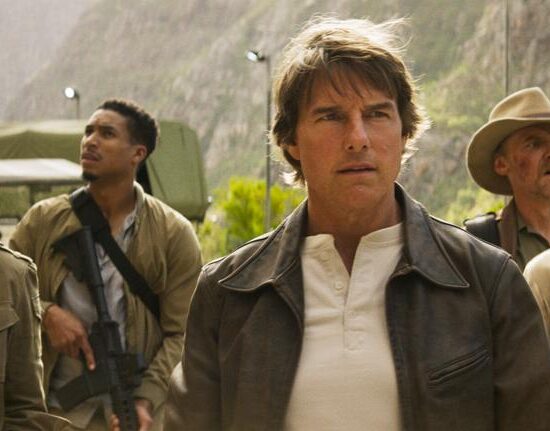

Ewan McGregor (and mustache) at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in June

A Gentleman in Moscow is in many ways a marker of Britain’s success, but the strikes have also come to symbolize just how enmeshed the UK screen industry is with the fortunes of the U.S. “If America sneezes, Britain gets a cold,” says Tina Gharavi, director of Netflix’s noisy docudrama Queen Cleopatra.

On the sneeze scale, the strikes are an almighty harrumph. They are an existential battle for the wealth that has flowed from an era of dazzling creative abundance. The conflict will be ended with a deal that will almost certainly influence the commercial mechanics of content creation around the world.

Of the 15 Brits who spoke to Deadline for this piece, there was a heartfelt sense of solidarity with strikers. The cause is viewed as a noble one and fastidious efforts have been made to operate within the strict boundaries staked out by the WGA and SAG-AFTRA. Protests have been staged and well-attended, with the likes of Brian Cox and Charlie Brooker voicing solidarity under a sea of placards.

UK unions Equity and the Writers’ Guild of Great Britain (WGGB) have been flooded with a “profound” volume of calls from members wanting to do the right thing. Three months into the writers’ walkout, WGGB is not aware of a single case of a member being blacklisted for taking on struck work.

Equity, meanwhile, has gone above and beyond its duty to members. The union is briefing agents it doesn’t always see eye-to-eye with (a call with the Personal Managers’ Association is planned for today) and publicists, who have spoken of panic over press campaigns. One rep admits that they downed tools because they were so anxious about putting clients in a difficult position.

Equity General Secretary Paul W Fleming says there are basic misunderstandings about how actors are impacted, reminding people that it is SAG-AFTRA studio contracts that are in dispute, not the union itself. U.S. actors can continue to work outside of these deals, while those on Equity agreements must fulfill their contractual obligations. “It’s just the same as one railway company going on strike and another continuing to operate,” he explains.

“The Bastard Is The Blast Damage”

As people attempt to stay on the right side of picket lines, there is an undeniable degree of anguish that shoots have evaporated. “The bastard is the blast damage,” laments a senior source on a shuttered production. For many, it has evoked memories of the collective trauma that was the pandemic. “We had just wrapped our first film without masks and immediately ran into delays in getting a strike waiver for our next shoot,” says a frustrated independent feature producer.

When writers put their pens down in May, some major shoots were knocked off balance, but most persevered. The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power soldiered through its final 19 days at Bray Studios without its showrunners. House of the Dragon, filming at Warner Bros Studios Leavesden, remained airborne.

‘Silo’ stars Rebecca Ferguson

Apple

It took actors joining the picket line on July 13 for cameras to stop rolling on studio shoots in Britain. Deadline revealed this week that Silo, Apple TV+’s hit sci-fi series starring Rebecca Ferguson, has halted indefinitely at Hoddesdon Studios. Disney’s Star Wars series Andor has been shooting with actors on Equity contracts, but will soon be forced to pause. Big ticket movies downed by the strike include Deadpool 3 and Wicked.

Amateur, a 20th Century Studios terrorism thriller starring Rami Malek, was halfway through production when the feature’s hundreds of cast, crew, and contractors were put on hiatus. “It was such a strange energy,” recalls one person involved in the project, which also stars Rachel Brosnahan and Laurence Fishburne. “We had just hit shooting pace when suddenly, the rug was pulled out from underneath us.”

The source thinks that Disney was happy shuttering Amateur to demonstrate the “absolute impact” of the strike. Others suspect that it is a useful excuse for studios to throw a leash around spending and rebuild balance sheets. Disney CEO Bob Iger, an industry elder who many hoped could be a voice of reason, did little to disabuse people of these theories when he said SAG-AFTRA’s demands were not realistic. “There’s a lot of self-righteous froth going on at the moment,” the Amateur insider says.

eOne gave crew a week’s notice on A Gentleman in Moscow. People were released to work on other projects and the show’s set was put into storage. There is no guarantee that the team who worked on the series will be reunited. A freelancer on the show thinks it could be months before another project comes along, meaning they will have to dip into financial reserves usually saved for quieter winter months.

Philippa Childs, head of creative industry workers’ union Bectu, estimates that hundreds, if not thousands, of freelancers have lost work because of the strike. The union has already declared an “emergency” for unemployed freelancers in unscripted television.

It’s a tricky predicament for Bectu, which supports the action being taken by the WGA and SAG-AFTRA, but is equally concerned about the impact it is having on its members. Childs directs her frustration at the studios rather than the strikers, saying that the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers needs to “resolve this in a pragmatic way and let everybody get back to work.”

Some crew on Amateur were told it could be as long as six months before a resolution is reached. More optimistic estimates peg the timetable to September or October, with the Emmys being seen as a big symbolic moment in the conflict, though the awards look likely to move to January.

Actress Elizabeth Bower at Equity’s solidarity protest

“The critical thing in any industrial negotiations is that everybody leaves with some dignity,” says a senior UK union official. “The unions are going to have their strike. The studio bosses are going to see whether it can be broken. Everybody’s got to get back around the table. That’s six weeks at the very least.”

The longer the strike goes on, the more entrenched problems will become. Actors’ schedules will be thrown into chaos, prep time for returning shoots will increase, and employment issues will become thornier for unions. Equity is painstakingly helping individual members figure out if job opportunities are ethically compromised, verifying if vacancies have opened up because a SAG-AFTRA actor has been dismissed, or if job ads preclude members of the U.S. union from applying. Both of these issues are big red flags for British actors, but they will become harder to spot the longer the strike continues.

The “Perfect Storm” For Freelancers

There is a feeling that the disruption could scarcely have come at a worse time. The recovery from Covid has been fragile. Unscripted freelancers are reeling from a drastic commissioning slowdown, while rampant UK inflation and spiraling mortgage interest rates are causing financial headaches for the whole country. “It’s the perfect storm,” Childs acknowledges.

The Film And TV Charity says it had seen a notable uptick in inquiries from people in turmoil. “With the uncertainty many are facing this summer adding to anxiety already being caused by the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, we have definitely noticed an increase in the number of people applying for grants in recent weeks,” a spokeswoman says.

Sound stages are also being left vacant by the strikes, adding to the woes of UK studios, who are already in dispute with a government agency over eyewatering increases in property tax. Twickenham Studios, home to Bohemian Rhapsody, has seen summer bookings being moved to the fall, when they are running into other commitments. Joint Managing Director Superna Sethi says: “It’s not an ideal situation and we empathize with all studios.”

The message from union leaders is clear: the pain will be worth it in the long run. They argue that if writers and actors secure a greater share of streaming revenues and ward off AI exploitation, the whole industry will win.

Equity chief Paul Fleming

“We’re using our position to advance a broader struggle of workers in the entertainment industry,” says Equity’s Fleming. Lisa Holdsworth, Chair of the WGGB, adds: “If people are paid properly, that always has a knock-on effect for everybody in terms of understanding the value of people’s work and their creativity.”

This argument has resonated with some. “I’d be happy to lose the work for better conditions because the erosion of rights is so diabolical,” says BAFTA-nominated director Gharavi. “It’s also part of the politics of why we make films in the first place — it’s about making society a better place.”

Jon Thoday, the powerful British talent agent, agrees that the disruption will be worthwhile. He tells Deadline: “I would hope that the result of the strike will be a proper acknowledgment of how talent should be rewarded when a show is streamed. There’s a positive medium to long-term aspect to all of this, and I think the studio that starts doing it first will win the streaming wars in the end.”

He says the strikes have opened unexpected opportunities. His company Avalon makes HBO’s Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, which has gone dark because of the writers’ strike. Oliver is now embarking on a rare standup tour in America. “Talent tends to find a place to entertain,” Thoday smiles.

Others are optimistic that the British indie film scene can get a boost. Gharavi is awaiting a SAG-AFTRA waiver for her Virginia Woolf rom-com Night and Day, starring The Girl On The Train actress Haley Bennett. UK producers have welcomed SAG-AFTRA’s transparency in publishing waiver grants on its website, but there have been a few raised eyebrows at big indies, including A24 and Lionsgate, being at the front of the queue.

Others are considering prioritizing projects originally planned for 2024. Nick Love, writer and director of The Sweeney and The Football Factory, is working on a low-budget feature that could reunite him with Danny Dyer. “It’s going to be interesting to see whether we can fast-track that. I’m just finishing a script now, but we’re going to go all guns blazing for it,” he says.

Eben Bolter, a cinematographer who has worked on The Last Of Us, urged SAG-AFTRA actors to “lend their name” to independent films in the UK. “Studios have space, kit is on shelves, crew are at home waiting,” he tweeted.

Some are more skeptical about SAG-AFTRA stars being swept up by indie features, given that many will be on “first position contracts,” meaning they will be expected to return to studio projects at short notice when the strike ends. “Actors may find themselves in a place of conflict where they are effectively bigamists between two partners,” says a high-profile director.

Britain Becomes Victim Of Its Own Success

The director, who wishes to remain anonymous, says Britain is more exposed to the strikes than many other production hubs because the industry is moored so closely to American shores. “That’s the UK being a victim of its own success,” he argues.

Max Rumney, Deputy CEO of UK producer trade group Pact, says the past two years of inward investment have been “quite exceptional” because studios were playing catch-up following Covid. Childs agrees that the influx of American work has been a coup for British business, but she worries it has come at the expense of domestic production. “We should be looking at how we better support UK filmmaking,” Childs adds.

‘Jurassic World: Dominion’ was filmed in the UK and was among the top-grossing movies

British Film Institute figures lay bare this disparity. Some 92% of the UK’s record £6.3B production spend in 2021 was from overseas shoots being housed in Britain. At the same time, domestic spending on TV and film projects fell by 4% and 31% respectively. This carries over at the UK box office, where last year’s top 34 highest-grossing movies all came from major U.S. theatrical studios, according to the Film Distributors’ Association.

A reexamination of Britain’s role as a production hub for America would be an unexpected and unlikely outcome of the strikes, but the industrial action will be a catalyst for change — even if it is not immediate. Every British union leader who spoke to Deadline says they will watch the U.S. negotiations closely, keeping in mind their own labor deals.

The WGGB has rolling negotiations with UK broadcasters and Holdsworth, the union’s Chair, says the outcome on residuals will have a “knock-on effect” for British writers. “If you want an industry that doesn’t necessarily compete with the Americans, but is of a quality of the American output, then you have to pay your talent,” she says.