“And so each venture is a new beginning, a raid on the inarticulate with shabby equipment always deteriorating…” So goes one of the many richly etched lines in T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Eliot, one of Britain, as well as—by history’s judging—the world’s pre-eminent poets, felt that any poem’s essential meaning had to be contended for and discovered. So it is, then, that director Sophie Fiennes has ventured with Four Quartets, creating something wholly distinctive and unquestionably resounding but also something imprecise.

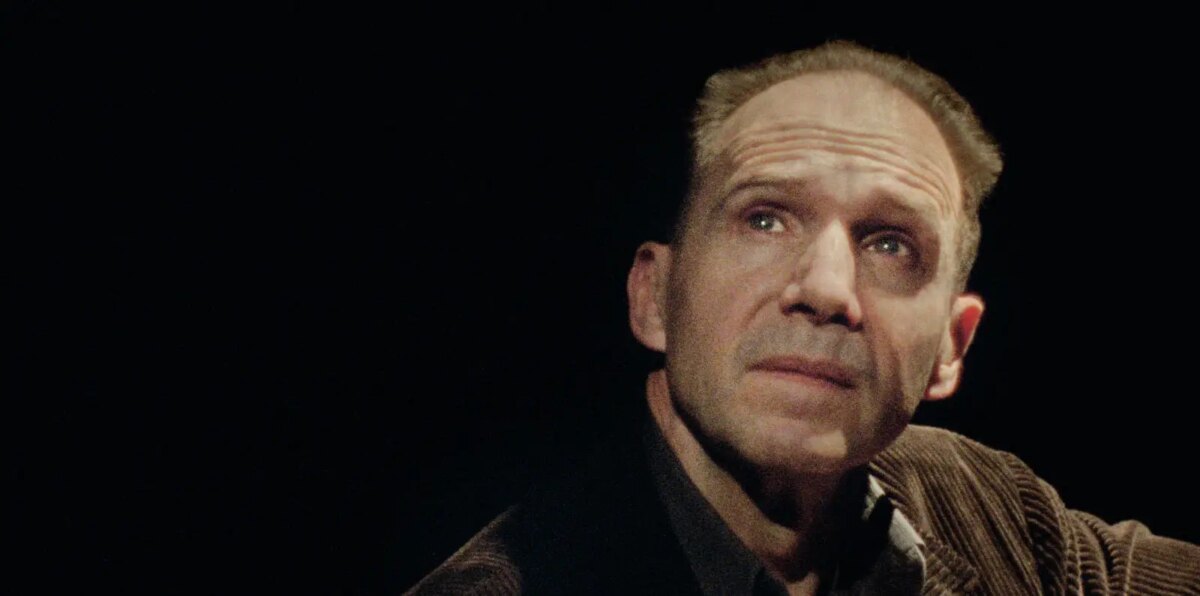

Four Quartets is the translation for the televised screen of Ralph Fiennes’ one-man theatrical performance of the very same T.S. Eliot work (Director and actor, in this case, being sister and brother). Eliot’s work was penned in the wake of the Second World War. Split into four smaller poems, Four Quartets is a dense but sumptuously considered series of ruminations on time, purpose, faith, and existence.

Particularly noteworthy of Fiennes’ performance on-stage is that he memorized Four Quartets in its entirety—nearly 1,000 lines of intricate and difficult poetry, to put it in perspective. However, therein enters the aforementioned imprecision: The magnitude of that fact certainly cannot be felt in any direction when witnessing it on screen, and so too is the intimate theatrical context lost.

“Eliot’s work was penned in the wake of the Second World War. Split into four smaller poems…”

What’s left is a suite of oddly integrated visuals. At times they are wonderfully transportive—showing, for example, the verdant garden of the manor Burnt Norton, which inspired the name of Four Quartets’ first poem—and at other times, starkly dull—showing, for the majority of the Fiennes’ performance, his figure cast against ghastly monoliths of concrete. What makes the latter particularly confusing is that the inherent nakedness of this setup is occasionally utilized to rather profound effect, such as when Fiennes performs whilst sitting at a table, speaking into a wartime microphone, alluding to the era of the poem’s inception.

I suspect the stripped-down aesthetic was designed to highlight the harrowing nature of the time and to highlight Fiennes himself, who is in riveting form. His chosen articulations and emphases give Eliot’s work a trancelike persona. And the words of Eliot’s pen are as intensely metaphorical and as decadently sublime as ever. Thus, it is a pity that the program runs for an hour and twenty minutes—likely twenty minutes too long. It is meticulous work to digest poetry of such a nature, and one’s attention—without better visual aid—wanders almost invariably. Splitting the performance into four episodes would have better served the televised format.

Still, Four Quartets is a special experience. There is something quite prescient about this work being rendered on the screen in the frenetic modern age. For those who can gather the patience, it is a reminder of the wisdom Eliot so treasured, with all its overt Christian inspiration, birthed with such difficulty in the fires of war. There are many who will feel Eliot’s stanzas require too much toil, and toil though Four Quartets may sometimes be, it is nonetheless timeless and unendingly beautiful.