If you look at a picture of a train, can you hear it? Or a picture of a crying baby? What if you see someone’s hand on a chalkboard, with fingers curved and spread, and fingernails biting in… Can you hear that?

For most of us, life is a multi-sensory experience. Objects that are completely silent are rare (clouds, for example), and so we constantly see with our ears. Hands clapping, children screaming, an earthquake, a rainstorm, an orchestra, a bus ride. We hear as we see.

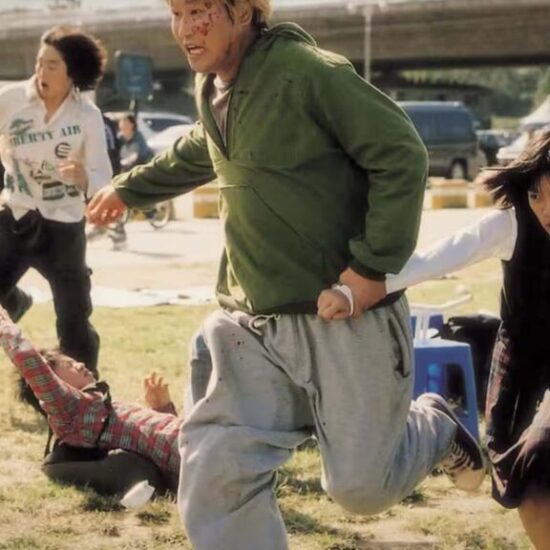

But what if what you see is injustice? Or a couple quarreling. Or an exhausted refugee, barely walking. A basketball team winning a tournament. Deforestation. Getting a college acceptance letter. A family getting evicted. Or simply a heartbreak. Does heartbreak have a sound?

One approach to writing music for film is to mix and match, try different things, see what “fits best”. This is when filmmakers usually work with libraries and publishers, trying to find the perfect match to support the image.

But what if the music emerges from the image, the same way the sound of a train emerges from a picture of a train? It is not an “add-on”, but an intrinsic property of the image.

Yes, we have to admit, it’s more challenging to extract sound from an emotionally charged situation than from a mechanical object, which simply cannot escape the physics of its own engine. One person may hear a heartbreak completely differently from another.

But if it’s true what they say, that music is a “universal language” of some sorts, then isn’t it also true that there could be a “universal soundtrack” to a heartbreak? Or rather, that all music that emerges from heartbreak shares something in common? And the same goes with other scenes and emotions. Perhaps there’s something in common among all soundtracks depicting loneliness, or a sense of loss, or the victory of overcoming.

Let’s reflect on the nature of that common aspect. Could it perhaps be a certain type of instrumentation? Or some specific harmonies? Musical intervals of some sorts? We could certainly analyze plenty of soundtracks, and find technical commonalities, similar patterns in harmonies, etc. For example, sparse instrumentation, unresolved harmonies, and plenty of sweet lingering dissonances are great tools for the composer wishing to write “lonely” music. But it only takes a few exceptions to the rule to turn this idea upside down. A thick, bass-heavy, synthesizer sound echoing through layers of reverb can be just as lonely as a solo violin playing thin harmonics. And there is also a way to write simple consonant music in a major key, using the full symphony orchestra, and still end up sounding sad, even desperate.

It seems then that if all music that emerges from a scene of heartbreak shares something in common, it is not at the technical/instrumental level, but rather at a human and emotional level. The tools may be varied, but the effect of music, as it reverberates in our emotional selves, intimately correlates from person to person.

When people cry during movies, they usually cry around the same time. When listeners get goosebumps while listening to music, they also tend to be coordinated.

How exactly music succeeds in triggering common emotions among a wide population is a highly complex subject, studied and discussed by neurologists such as Daniel Levitin and Oliver Sacks. Partly, it has to do with our biology and evolutionary roots. Daniel Levitin, for example, suggests in his book This Is Your Brain on Music, that the reason we humans enjoy repetition and a steady rhythm is because, in nature, repetitive sounds are sounds that are “safe” – the sound of the wind, ocean waves, leaves in the trees, etc. – whereas irregular, sudden sounds can be life-threatening – a lion’s roar, the sound of lightning, rocks tumbling down, etc. Next time you find yourself loathing Schoenberg’s music, you can put the blame on lions.

At the same time, one needs not to know exactly how an apple tree grows apples in order to crunch on one. Most of us find ourselves using electricity every day without truly understanding what electricity is. Likewise, we, at Vessels to Motherland, have been luring music out of films using our own method, working with an emotional substance whose inner workings we don’t quite understand:

We start by emptying ourselves of any musical idea, structure, or style, and we let ourselves be moved by the moving images. As we feel things, we listen to them attentively. Our emotional selves then become translators of some sorts, translating the moving image into sound. Each movie score we make ends up being very personal, like the journal entry of a person who lived through the film.

Through decades of music making, we came to the conclusion that in order to reach people’s hearts, in order to create music that is truly moving, that moves one “to the core”, we need to look inwards. We need to be moved ourselves. Hence, being a musician is equally being an orator and a listener, simultaneously. But perhaps “speaking while listening” is not an oxymoron if we invite the possibility that what speaks is not quite our selves…

…

Vessels to Motherland is a film composer ensemble and electroacoustic duo, based in NYC. If you are interested in collaborating with them on your next film, you can write to [email protected]. Other ways to connect: