Late in September, the Washington National Cathedral held a dedication ceremony for a quartet of new stained glass windows designed by painter Kerry James Marshall and fabricated by Andrew Goldkuhle, replacing ones that depicted Confederate generals Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and Robert E. Lee. Before the congregation and an assembled audience that included Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, Marshall made a short speech that was as funny as it was poignant. (It’s worth looking up on YouTube.)

“I’ve spent my entire life making pictures, so I don’t hold any delusions about the transformative powers of artworks,” he said. “Not enough people ever see them to interrupt the dynamism and the challenges we face living from day to day. What they can do, however, is to invite us, and anybody who sees them, to reflect on the propositions they present.”

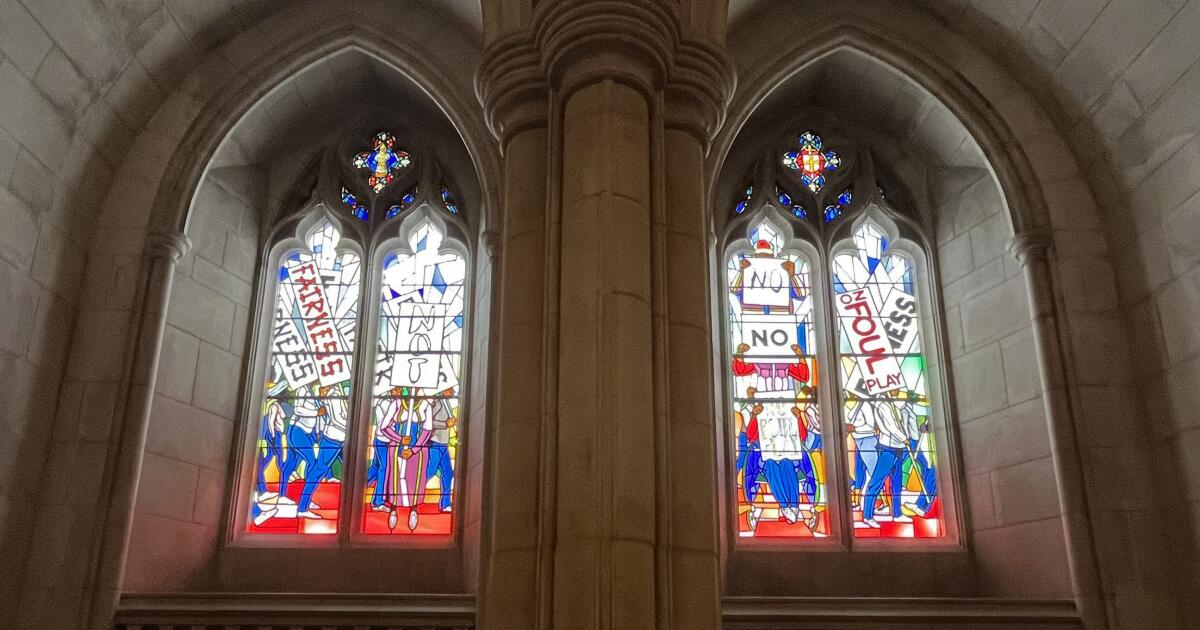

The proposition of Marshall’s windows, formally titled “Now and Forever,” is an intriguing one. The windows do away with the plaintive or supplicating figures more common to Christian stained glass. In their place is a group of Black marchers at a protest. Their cause isn’t stated, and the figures are anonymized, their faces largely obscured behind posters that read “FAIRNESS” and “NO FOUL PLAY.” Behind the marchers, an abstracted pattern rendered in blue and white evokes the angular dimensions of an urban environment. These everyperson marchers could be in Anycity, U.S.A.

Kerry James Marshall’s stained glass designs honor peaceful protest.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

Black figures bearing protest signs certainly evoke the mass actions of the civil rights movement and the more recent Black Lives Matter marches, but they also represent the innumerable other protests that have molded everything from the laws that govern our bodies to the policies that govern the land. I happened to arrive in D.C. the day after a massive peaceful protest in support of a cease-fire in Gaza, which had left its residue around the city: discarded fliers reading “Stand with Palestine” and stickers on a light post demanding, “Ceasefire Now!”

What role did protest play in giving urgency to the all-too-brief cease-fire? And what role might it play in the future? That’s impossible to tell at this juncture. But. unlike a single work of art that few may ever see, protest — peaceful, collective dissent — is an act that can have transformative power.

The National Cathedral is a curious building. Begun in 1907, it was constructed in the Gothic style, with its roots in the medieval era, at a time when Modernism was beginning to take hold. But the building is not simply a derivative throwback. As it slowly rose (it was only completed in 1990), the ideas that shaped it evolved — an evolution reflected in its decorative elements.

A vestibule area features depictions of human rights activists, such as slain Salvadoran Archbishop Oscar Romero and civil rights pioneer Rosa Parks. The capitals of the columns that support the colonnade bordering an enclosed garden don’t just feature angels and saints, but also Hopi dancers and an Inuit igloo. More amusingly, among the gargoyles and grotesques that dot the various towers are one in the form of a corrupt politician and another representing Darth Vader.

The stained glass windows have likewise evolved. These were designed by an array of artists. Rowan LeCompte, a Baltimore-born artisan, created more than three dozen windows for the cathedral, including the west rose window, which depicts the creation of Earth as an explosive abstraction of color and light. Also remarkable is a window designed by St. Louis-born Rodney Winfield to commemorate the Apollo 11 moon mission: a cosmic arrangement of deep purples and blues embedded with a piece of lunar rock.

A decorative carving on a column capital features a scene with an Inuit figure.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

The windows depicting Confederate Gens. Lee and Jackson — which included the Confederate battle flag — were donated to the Cathedral in 1953 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy (who declined to discuss the windows’ removal with a reporter for the Washington Post).

After a white supremacist murdered nine parishioners at a Black church in Charleston, S.C., in 2015, the cathedral put together a task force to evaluate the possibility of taking them down. But they weren’t removed until 2017 — after a man in Charlottesville, Va., rammed his truck into a group of counterdemonstrators protesting a white nationalist rally, injuring dozens and killing a young woman in the process. (To protest is to put the body at risk.)

“The windows became barriers for people to feel fully welcome here,” the Very Rev. Randolph Marshall Hollerith, dean of the cathedral, told the New York Times in 2021. “And so we came to the point where contextualization was no longer possible — but the windows needed to be removed from the sacred space.”

Marshall was commissioned to create a design that captured “both darkness and light, both the pain of yesterday and the promise of tomorrow.”

Artist Kerry James Marshall at the Washington National Cathedral for the inauguration of his stained glass windows on Sept. 23.

(Andrew Harnik / Associated Press)

Marshall is renowned as a painter, particularly of the Black figure. A terrific retrospective of his work was on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles in 2017. But the project for the cathedral, for which he charged a symbolic commission of $18.65 — a number that marks the end date of the Civil War — was the first time he worked with stained glass.

The windows, in some ways, mark the opposite of what Marshall is best known for: Blackness. His people have shimmering skins rendered in the blackest of tones; in some cases they camouflage themselves into shadow and night. One such canvas, his 1986 painting “Invisible Man,” is one of the defining works in the engaging group show “Going Dark: The Contemporary Figure at the Edge of Visibility” currently on view at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. And the Los Angeles County Museum of Art owns “A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self,” a painting that, likewise, features black on black.

In his stained glass, however, Marshall, turns to white light. His lancet windows feature entire segments, such as the protesters’ placards, crafted in different shades of white, allowing sunshine to come pouring through. The “Now and Forever” windows are among the brightest in the cathedral; elsewhere they are dominated by reds and blues. Marshall’s protesters literally let the sun shine in, a focal point as you navigate the nave.

Placed below the windows is a poem by Pulitzer Prize finalist Elizabeth Alexander titled “American Song.” “Aspire to song,” it reads. “Aspire to the lift of voices joined to make a mighty noise.”

I’m intrigued by Marshall’s windows for the way they honor the collective over the individual — part of a wave of monuments that are rethinking how we honor history. Monuments historically celebrate men and focus on war; Marshall’s windows make us consider the groundswell movements that have been as significant to altering the course of history as any top-down battlefield bravery.

Marshall isn’t the only artist to engage protest as a topic.

Currently, I’m on jury duty in downtown Los Angeles (writing this while on a break) and have been taking the Metro to get to court. On a daily basis, I emerge from the Historic Broadway station to a public art installation by L.A. artist Andrea Bowers, which features the popular Spanish-language protest phrase “El pueblo unido jamás será vencido” (The people united will never be defeated) popularized in song by Chilean group Quilapayún in the 1970s.

Andrea Bowers created “The People United”for Metro’s Historic Broadway station in downtown L.A.

(Carolina A. Miranda / Los Angeles Times)

Every time I lay eyes on Bowers’ installation, rendered in bright multicolored letters over contrasting blocks of color, I feel like I’m amid the buoyant voices that, as Alexander writes, come together “to make a mighty noise.”

And what a noise worth celebrating.

Now and Forever Windows

Where: Washington National Cathedral, 3101 Wisconsin Ave., N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016

Admission

Admission: General sightseeing admission $18; specialty tours from $30. (It is recommended to purchase tickets online in advance.)

Info: cathedral.org