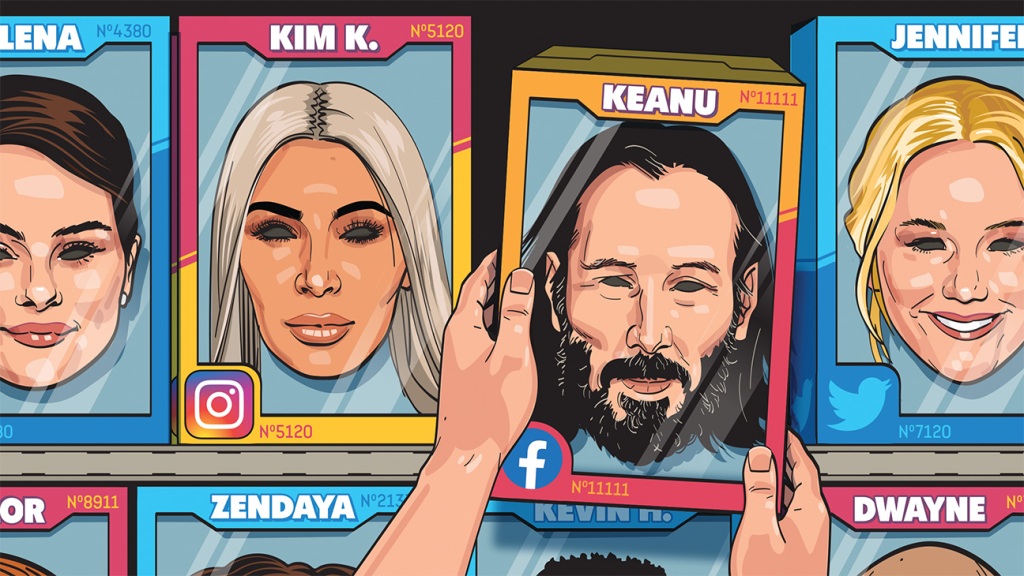

Type in any celebrity’s name on Instagram or Twitter and you’re bound to find at least a handful of accounts — if not more — posing as the celebrity, using the same profile picture and sharing photos and videos taken from their real accounts.

Some of them are innocuous fan accounts dedicated to sharing the latest updates on their favorite stars with other stans. But others — the true impostors — can cause much more harm, DMing unsuspecting fans to scam users out of money, solicit nude photos or otherwise exploit a celebrity’s star status.

Though social media platforms now have sophisticated AI-powered technology that can help weed out possible fraudsters among their millions of users, public figures still must contend with the potential for their likeness to be ripped off for someone else’s gain. In fact, Twitter’s verification program launched in 2009 after St. Louis Cardinals manager Tony La Russa sued Twitter for emotional distress after a user made an account in his name and tweeted offensive comments.

Since then, a blue check mark has been adopted across most social platforms to identify the real accounts of public figures, businesses and journalists to help users distinguish legitimate accounts from fakes. But impostor accounts still exist, and aside from working directly with the platform to identify and remove them, there isn’t much that stars and their teams can do to tamp down their proliferation.

That’s why some stars retain services like Social Impostor, which takes on the grunt work of helping talent identify fakes and works with the social platforms to take down those accounts. The service is run by Kevin Long, who says he’s been in the business of removing fake social media accounts for top talent and public figures for 12 years. (Long declines to name any of his clients because of nondisclosure agreements.)

When he first started, Long developed his own data tool that would scrape the APIs (application programming interfaces) of each platform and sift through impostor accounts. From there, he would manually scan the lists and work with staffers from the social platforms to shut down fake accounts. But Long says that after Facebook’s 2016 Cambridge Analytica scandal — a massive data breach that resulted in tens of millions of Facebook users’ data being harvested by a data firm to build profiles on U.S. voters — most platforms placed major limits on his tool’s ability to scrape for account data. As a result, Long typically must manually search through account names, making his work much more tedious and time-consuming.

It also doesn’t help, Long says, that the social platforms don’t prioritize removing impostors’ accounts — and each has its own guidelines dictating what will result in an account being taken down. Timelines for removal also differ, and users may have to wait days or weeks before action is taken.

“The people that are in high value [i.e., prioritized by social media companies] are engineers and people who continue to develop products that bring in money or revenue streams; [they] are more important than people who are there to try and review accounts that have been taken down or to take accounts down,” Long says. “In the end, they want to have more accounts up, not less, so it’s been a constant battle.”

Twitter set NBA fans abuzz in November, when paid subscriber

@KINGJamez (just one character off from LeBron’s real @KingJames handle) announced he wanted the Lakers to trade him. The blue check and same profile picture made the fake account seem authentic.

Stars may also consider pursuing legal action against people running impostor accounts, though attorneys don’t recommend doing so. “It’s just not worth it,” says Greg Korn, a partner at Kinsella Weitzman. “The damages wouldn’t be high enough and the fees would be extraordinary to try to chase somebody down. There’s just no bang for the buck.”

That didn’t stop former Real Housewives star Bethenny Frankel from suing TikTok last October, when she claimed the platform profited by failing to identify and remove advertising partners that misappropriated her image to sell products. But in that case, which was moved to arbitration in January, Frankel pursued the platform itself and not the individual or business that she alleged misused her image to promote a cardigan in an ad.

Talent agencies may also get involved to help clients dealing with impostor accounts. At UTA, for example, the IQ Talent Strategy team will flag the fake accounts to platforms for assistance. For high-profile clients, the process is usually more straightforward, but the team may encounter issues if an account is posing as the manager or agent for a client.

The process is easier with platforms like Meta than with Twitter, which no longer has an entertainment partnerships division to facilitate such requests. And despite Twitter chief Elon Musk’s professed stance against fake accounts, his laissez-faire approach to verification appears to bolster them. As Twitter pushes its subscription Twitter Blue product, anyone with a phone number and $8 a month to burn can become verified; users have since sought to prove the uselessness of paid verification by exploiting its loopholes and creating accounts posing as other individuals or organizations. Though many of those efforts have been in jest, there have been real consequences for some businesses: Last November, as Musk was still rolling out his paid verification plan, an account posing as the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly announced that it was making insulin free. As the company scrambled to get the account taken down, Eli Lilly pulled advertising dollars from Twitter and saw its own stock drop by 4 percent, though it’s not entirely clear how much of the stock drop was due to the fake announcement.

Meta — the parent company of Facebook and Instagram — has followed suit by rolling out a paid verification program, offering blue verification badges for $14.99 a month with a slightly stronger verification process that requires a government ID and a selfie video.

But, as Monica Lewinsky noted, all it takes is one lie from an impostor account to go viral for damage to be done. “In what universe is this fair to people who can suffer consequences for being impersonated? A lie travels half way around the world before truth even gets out the door,” Lewinsky tweeted on March 26, sharing screenshots of Twitter accounts posing as her — including one with a blue verification badge.

“Keanu Reeves” has requested to connect with more than one THR staffer on LinkedIn (the actor famously doesn’t use social media), and Monica Lewinsky called out a blue check impostor in March, writing, “This is going to be fun.”

“Everybody’s got different levels of tolerance for the damage that an impostor account might do to them, and sometimes it’s only when you hit DEFCON 3, when somebody has requested nudes from a teenager or has somehow fooled some member of your family … that they finally say, ‘OK, enough,’ ” Long says. “But it’s really something that ought to be part of every agent’s or lawyer’s package to help provide cybersecurity for [entertainers] in this day and age. Because you never know what people are doing or saying using your name, and you don’t want to have fans or followers be victimized by these folks.”

This story first appeared in the April 12 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.