As Star Wars fans tell it, the 1977 film was nearly doomed. Graced by the magic fingers of George Lucas’s wife, Marcia Lucas, the sci-fi space opera was “saved in the editing.”

This has a ring of truth to it, but not quite in the way that you might think. Though the new team of editors is presented as the heroes in this story, that ignores how films — then and now — are made. Star Wars was no different from any film ever made, it too just another messy, arduous scramble.

At the heart of this specific Star Wars myth lies the “lost cut,” an abandoned edit that was so bad that the film needed to be completely re-edited from beginning to end. The odd segments were pruned to allow the movie to flourish. Many of the doomed scenes, subplots, and characters in said lost cut were discarded only to pop up in DVD releases or special editions decades later, proving their existence.

One look at a sampling of the scenes left on the cutting room floor, and it becomes apparent why. No director really knows what works until they see it on film. That’s no one’s fault.

Is there really a “lost cut” of Star Wars? Yes, because it has been screened. Also, no, because there is no single “lost cut,” and it is not entirely clear if this version in question was ever intended to be a real edit. Before the film was completed things were already getting complicated, and they only got more muddled in following years.

False Starts

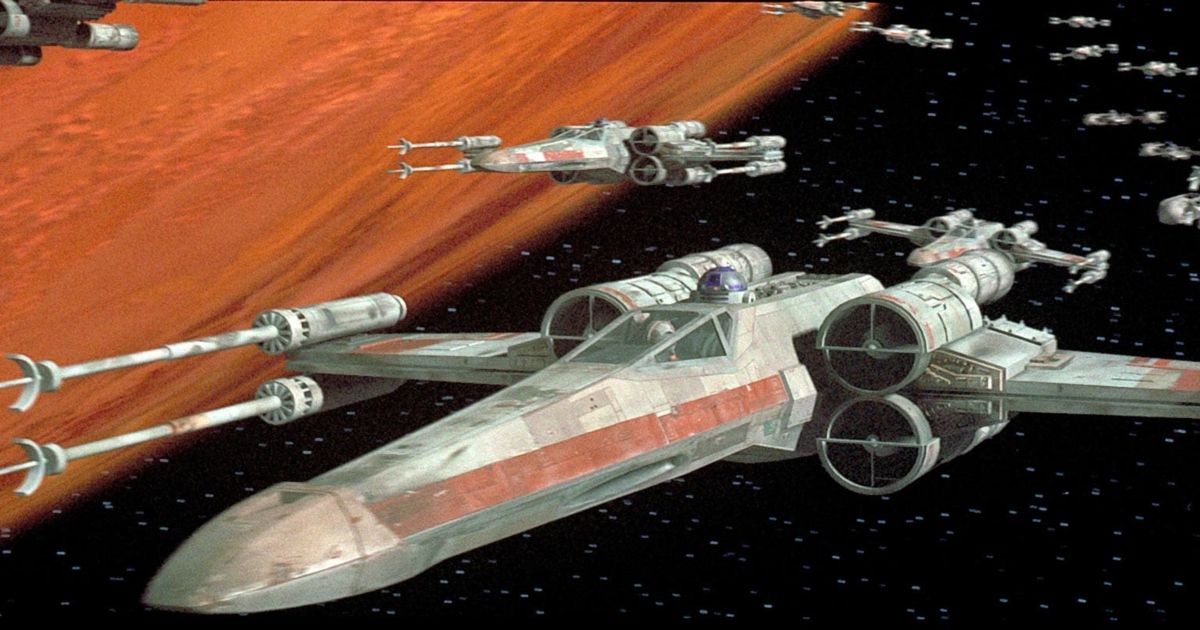

Running over three hours, the task of hewing the heap of celluloid initially fell to John Jympson, Lucas wanting to see what he had before effects were added in post-production by Industrial Light and Magic (ILM). Sensing the film lacked heart and coherence, on the brink of a heart attack, Lucas opted for someone he trusted more, his wife Marcia. She had her work cut out for her, the climactic battle alone coming to 40,000 feet of film (via George Lucas: A Life). Lucas boasted, “I think it took her eight week to cut that battle.”

She needed help. With the work of two more extra editors slaving in the cutting room, Lucas’ project was given a jolt of pathos, Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas, and Richard Chew eventually winning an Oscar for their toil, each overwhelmed by the task. Chew commented it was necessary to “let the actors’ rhythms dictate the cuts rather than having the cuts drive the rhythm of the scenes,” allowing the characters to propel the plot not the dry mechanics of the script. That’s about the most expert opinion we have on the lost cut. However, to say that they saved the movie is meaningless. Editing makes or breaks every film. Go look at any one of the hundred versions of Blade Runner for further elucidation.

According to available sources, Lucas took offense at the haphazard way Jympson paced the action. Also of note, there was much debate which takes were the best ones. The drama behind the set had as much to do with a clash of personalities as it did with the edit, if we are really being honest, Lucas in constant conflict with his editor Jympson and the cinematographer. By the end of filming, both were trashing him behind his back. Jympson might have produced a terrific edit himself for Lucas given a few months to do the work it took three editors to pull off, but the two men’s working relationship was beyond repair. According to most have seen both versions, the original and theatrical 1977 cut, audiences lucked out. Then, what of the original version as edited by Jympson?

Unearthing the “Holy Grail”

For years the first draft of the film was forgotten. Who better to dig up the past than David West Reynolds, an actual archaeologist? Having spent some years in the early nineties trying to locate the set of Luke’s Skywalker’s childhood home in the desert of Tunisia, Reynolds turned to the original work-print.

Reynolds had become close to George Lucas, and was given unprecedented access to rare materials and secret information. A writer for the magazine Star Wars Insider, Reynolds described one such exotic curiosity he had the pleasure to watch, the unaltered base that all future iterations of the movie were built upon. After decades in storage, the so-called “lost cut” was publicized to the world. It was not so lost after all, and, if digitized, likely in decent shape unlike most nitrate film.

Don’t get excited. Barring a change of heart, Lucas — who sold away Lucasfilm rights in 2012 — will never reveal this work-in-progress copy. As the copyright of the film is now in the hands of Disney (as are the characters and the work print), the right to distribute the film is presumably not something Lucas has any say in. To say nothing of which “cut” would qualify as the “lost” version, seeing as there are traditionally multiple rough cuts made during filming, both with and without effects, without audio dubs (Darth Vader’s spine-chilling voice not added in until after the film wrapped), different takes with different blocking, and unedited scenes later tweaked for the theatrical release.

The Next Best Thing?

There is yet another lost Star Wars, that one being the version that was shown in theaters in August 1977. Lucas has gotten carried away with re-editing existing classics in his time, and no film has fallen prey more than the first Star Wars film, aka Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. Even that title was retroactively “enhanced.” This time we might just be able to bypass Lucasfilm and Disney altogether.

And here it really starts to get tricky. Fan edits, even for the noblest purposes of preservation, are outside traditional boundaries of fair use, their legality not immediately justifiable. Over the years, fans have cobbled together bits of pieces of releases from different medium, Laserdiscs, VHS tapes, etc. to make one single “Despecialized Edition.” This is an imperfect science, each clip of varying audio and visual fidelity, requiring the audio from one film to be stapled onto the picture of another reel, skipping around where necessary, the differences in clarity, resolution, and color grading a dead giveaway.

As the title suggests, this version completely excises all the superfluous enhancements and late additions that have divided fans for years, removing the offending Han vs Greedo re-edit in an attempt to recapture the authentic Star Wars. One such source, known as “Puggo Grande” (a digitized 16mm widescreen cut of the film) is frequently used as a guide to indicate where Lucas made cuts and slipped in new footage or added new effects. The donor of this intact, albeit grainy film, wished to remain anonymous, the only real clue we have is that some clips bore Swedish subtitles.

Many of these copies are currently circulating around the web. For legal reasons, we will not post links to them, but their existence, and the whole of the lost cut preservation project, raises a necessary point about when art should be preserved and whom should be entrusted to undertake that preservation. Countless writers before Lucas have instructed their notes or unfinished work to be destroyed, putting him in some esteemed company. But Star Wars, whether George likes it or not, is now bigger than him.