If anything, the title of Netflix’s Mulligan is understating its premise. The animated comedy isn’t about just any second chance, but arguably the ultimate second chance: the chance to rebuild society, but better, in the wake of an alien attack that’s apparently wiped out all of humankind besides a thousand or so souls in the Washington, D.C., metro area.

Its central joke, however, is that there isn’t really any such thing as a clean slate. The world may have changed, but people fundamentally haven’t, and so most of its 10 half-hour episodes are spent watching humanity fumble their way back toward the same bad habits that doomed them the first time. But it’s one thing for characters to retreat into old patterns. It’s another for a series to do so. The great disappointment of Mulligan, created by Sam Means and Robert Carlock (Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt), is that all of it feels like it’s been done before, better, elsewhere.

Mulligan

The Bottom Line

A squandered opportunity.

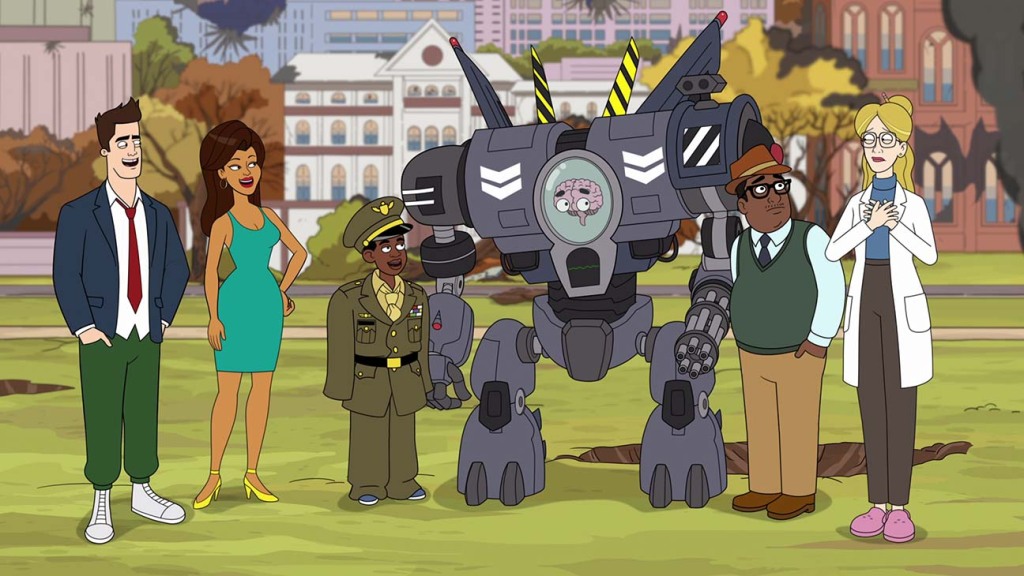

Mulligan starts at the end of the world, with Earth already under fire from an army of bug-like green aliens from the planet Cardi-B. (Not like the rapper, the extraterrestrials insist: “It’s a coincidence!”) But just when all seems lost, Matty Mulligan (Nat Faxon), a single-A baseball bro from Boston, stops the attack in its tracks with a well-aimed grenade throw. Hailed as a hero, he’s quickly named the new president of the United States and surrounded by a tight circle of advisors.

The most prominent is Senator Cartwright LaMarr (Dana Carvey), a Mitch McConnell type who sees in Matty an opportunity to install himself as the Dick Cheney to Matty’s Dubya. But there’s also DARPA scientist Farrah (Tina Fey), Georgetown history post-doc Simon (Sam Richardson), and former Miss America Lucy (Chrissy Teigen), the latter of whom becomes Matty’s First Lady. These three see in the apocalypse an opportunity to correct the mistakes of the past — but to get the job done, they’ll have to overcome both Matty’s Idiocracy-level stupidity and LaMarr’s underhanded scheming, as well as their own lingering hangups.

There’s narrative potential in the way Mulligan subverts the fantasy of burning it all down to start fresh, as represented in so many despairing editorials or post-apocalyptic fictions. LaMarr, a reactionary who recoiled from newfangled notions like “The Jeffersons, lady doctors and phones [that] let you press a button to talk in Spanish” well before the attack, may be the only explicitly conservative character, but he’s not the only one unable to get over the world that was. The saying goes that those who forget their history are doomed to repeat it. But in Mulligan even Simon the history nerd just finds new ways to get bullied by jocks or strike out with women, no matter that the surviving population is two-thirds female. (The men, we’re told, perished either in the alien battle or in jet ski and fireworks accidents shortly thereafter.)

Some of the echoes of the past are even kinda clever. With the electrical grid down and traditional news institutions demolished, the news cycle becomes a literal news cycle — that is, a guy on a bike yelling updates at his fellow citizens. Over the course of the season, however, what began as a modest act of community service devolves into bread-and-circuses infotainment, culminating in a live Bachelor-style reality show that’s actually just a crowd gathering to watch a woman pick between two suitors in real time. It’s more wry in an I-see-what-you-did-there way than hilarious in a laugh-out-loud way, but it’s nevertheless amusing to see how quickly good intentions can go south.

But the vast majority of Mulligan feels about as ambitious as its title character, who spends much of the season trying to find the national treasure from National Treasure. Where Carlock and Means’ other shows, including 30 Rock, Great News and Girls5eva, pushed past familiar stereotypes to turn their characters into unique and specific weirdos, Mulligan falls back on tired tropes about Massholes who hate the Yankees or women trying to have it all. Where those other shows delighted fans with the sheer density of their jokes, Mulligan gets in maybe two decent laughs an episode, and only occasionally crams funny details into its flat, simple backgrounds.

Its pop culture references, too, are oddly stale. There’s nothing necessarily wrong with referencing Hitch or The Handmaid’s Tale or Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, and it totally tracks that Matty is still doing Borat in 2023. But when a character’s go-to example of a backfiring celebrity song performance is the DNC’s “Fight Song” video from 2016 and not Gal Gadot’s “Imagine” video, Mulligan feels like a script that’s been gathering dust on a shelf for the past seven years.

Mulligan does improve a little over the course of the season, especially as it as gives itself over to sillier plotlines like an egg hunt gone monstrously awry. Axatrax (Phil LaMarr), the alien general being held hostage on Earth, is usually good for some chuckles, whether he’s furiously plotting his escape or trying to blend in with the population in a Bill Clinton mask. (The disguise turns out to work because everyone buys that “Bill Clinton” might be the sort of creep who stands around announcing stuff like “Boy, the penis I have sure hurts, just dangling there externally.”) A subplot about Farrah’s robot assistant TOD-209 (Kevin Michael Richardson) trying to remember his previous life as a man is really just a riff on RoboCop, but it’s deployed effectively as a counterpoint to the humans’ very human tendency to think only about themselves. And while Simon isn’t particularly an exciting spin on the geek archetype, Sam Richardson continues to show a knack for spinning comedy gold from uninspired straw.

Those flashes of humor or mild insight come too rarely, though, to save Mulligan as a whole. It’s possible, I suppose, to imagine this show coming back better someday with tighter pacing, sharper jokes and more memorable characters. But if there’s one thing the series makes a point of showing us, it’s that second chances aren’t always all they’re cracked up to be. The world will always be worth saving. Not all the TV that comes out of it will.