On its surface, David Auburn’s “Summer, 1976” airs the flimsiest of subjects: Two very different women of approximately the same age strike up a close friendship that endures for only a few months. The fact that the two women never really bond in a way that will survive the summer of 1976 is the tension that slyly drives the narrative.

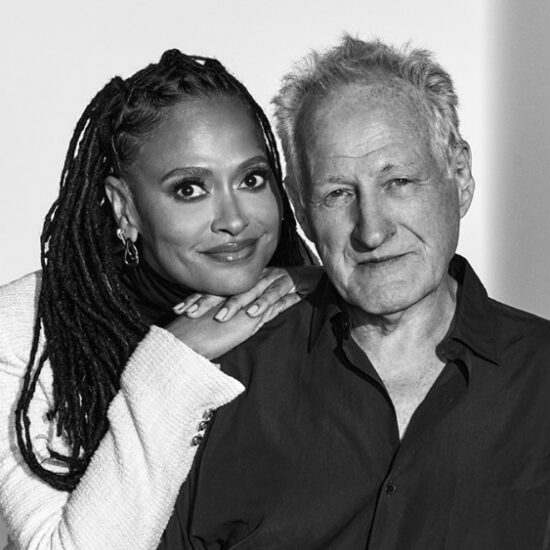

This odd but very absorbing two-hander starring Laura Linney and Jessica Hecht had its world premiere Tuesday at MTC’s Broadway venue, the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre.

The table-and-chairs set by John Lee Beatty is also flimsy, at first glance. Thanks to Japhy Weideman’s lighting and Hana S. Kim’s projections, it expands subtly to suggest a number of locales beyond what it first appears to be, which is a conference room decorated with a 1970s modernity that has never returned to being fashionable. Linney and Hecht begin the play by walking onto the stage and taking their respective seats.

For some veteran theatergoers, there may be an immediate moment of dread when it is strongly suggested that the two actors will never leave those two chairs. If Jessica Chastain can stay seated for most of “A Doll’s House,” anything is possible. From their first utterances, the two actors in “Summer, 1976” play to type for those veteran theatergoers who know their respective stage personas. Linney is all icy reserve, judgmental to the point of nitpicking. Hecht is all fuzzy and flighty, to the point of being downright loopy. Their characters, Diana (Linney) and Alice (Hecht), admit early on in the play that they became friends because each had a five-year-old daughter and those two girls adored each other. What else are two such mothers in their 20s to do but put up with each other until circumstances push them into an intense but short-lived friendship? There’s a very different need in each of them that is momentarily fulfilled, and when circumstances change, the relationship they’ve created doesn’t so much end as slowly fade away.

Linney and Hecht are not in their 20s, and so “Summer, 1976” is very much a memory play. They don’t so much enact what happened that year but rather tell us what happened. For those theatergoers who might have experienced a moment of dread as soon as these two actors sat down and started to speak, there will also soon arrive a moment of relief when it is obvious that Linney and Hecht are in the hands of a great storyteller who knows precisely how to elevate the language to turn ordinary lives and events into something significant and worth our rapt attention.

Here’s how Diana describes Alice: “She thought of herself as a ‘free spirit,’ but she was in the most conventional of marriages. She wasn’t working; she was essentially living like a 1950s housewife. She just thought she was unconventional because her house was messy. I mean that’s all it was, really.”

When Alice surprises Diana with a joint to smoke, here’s how she describes her future friend: “Yeah, she f—ing bogarted it for, like, five minutes, and I was like, come on lady, I only took it out because it was the only way I could imagine getting through the next 10 minutes before I could make an excuse and leave.”

There are scenes in “Summer, 1976” that play out in real time. Linney occasionally takes the role of Alice’s husband, and Hecht briefly takes the role of Diana’s daughter. Beyond the non-gender and non-age specific casting here, the storytelling depends less on dramatic events than the tension created by two people with opposing world views. How long before Diana tires of Alice’s aggressive normality? How long before Alice resents Diana’s rigid control?

This review is purposefully very short on plot details, because with near mathematical precision Auburn parses one tantalizing revelation after another. (He achieved something similar with his Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “Proof.”) The pleasure of “Summer, 1976” is the anticipation of wondering what Diana and Alice will do next. Usually, it isn’t the sound of a shoe dropping but the soft splash of the ash falling from one of their shared joints of grass.

Directors of plays with small casts don’t have a great track record with the Tony Awards. Only once has the director of a two-hander play won the Tony: Michael Grandage, who directed “Red” in 2010. While two actors throwing a lot of red paint on a big canvas in record time was thrilling, director Daniel Sullivan delivers a far greater theatrical spectacle with Linney and Hecht attempting to communicate at often cross purposes for 90 minutes. His coordination of the technical elements is equally arresting.

In addition to Beatty, Weideman and Kim’s respective technical contributions, there is an impressionistic score by Greg Pliska that provides several musical longueurs when the two characters words and actions are misinterpreted. We wait for Alice and Diana to pick up the pieces to start over, and Pliska’s music gives us the opportunity to contemplate what just went wrong. It is also nice to see a sound design, by Jill BC Du Boff, where the actors aren’t encumbered with head mics and the accompanying taped-down wires that poke out from the back of the neck.