The proliferation of documentaries on streaming services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Each month, we’ll choose three nonfiction films — classics, overlooked recent docs and more — that will reward your time.

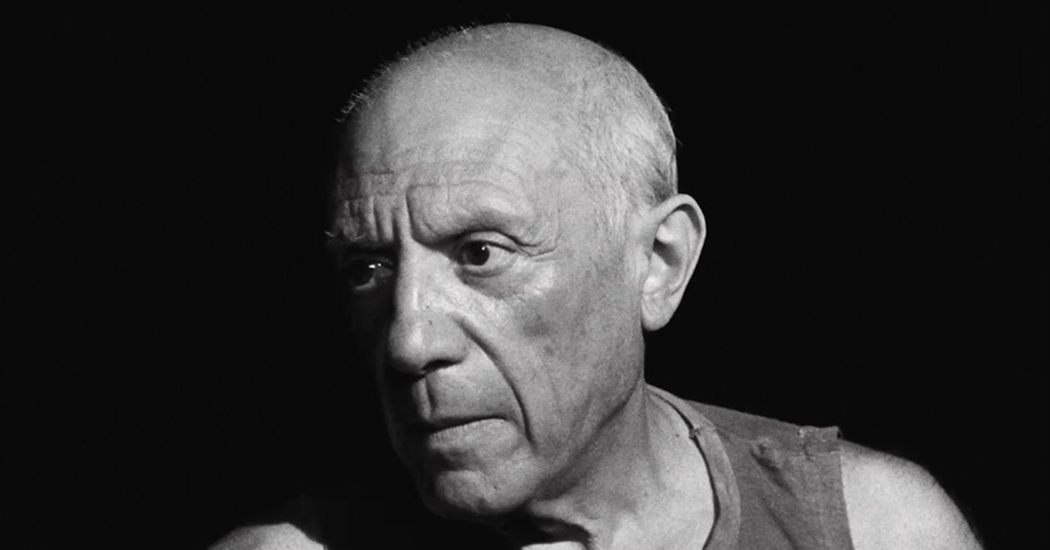

‘The Mystery of Picasso’ (1956)

Stream it on the Criterion Channel, Kanopy, Metrograph and Ovid. Rent it on Apple TV, Google Play, Kino Now, Milestone and Vudu.

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s documentary begins with the proposition that cinema can offer a glimpse into the “secret mechanism” that guides a creator — that it’s feasible, at least with painting, if not with music or poetry, to observe the artistic process as it occurs, to begin to understand what is happening in an artist’s head. To that end, the filmmaker has a shirtless Pablo Picasso engage in a marathon painting and drawing session for the camera. For the majority of the movie, we see only Picasso’s artwork, which fills the frame. Around the half-hour mark, Clouzot reveals how he has achieved this effect: Sitting on the other side of a page from the camera, Picasso is filling sheet after sheet of see-through paper. What the film captures are mirror images of whatever he is sketching.

Picasso says that he could paint all night. When, immediately after that remark, Clouzot informs him that the cinematographer has only five minutes of film left, Picasso replies, “It’ll do,” and proceeds to create what looks like a fish that morphs into a rooster that turns into a faintly feline inkblot face. To see Picasso improvise and revise is to want to shout, “Stop!” whenever the composition begins to look interesting, which is almost always immediately — and then to see the error of wanting to arrest his inspiration. The artworks change radically once he begins adding color and filling in the backgrounds, a progression that reveals a complexity barely hinted at in the initial drafting. The process isn’t necessarily shown in real time — editing speeds up hours into minutes (and makes Picasso’s revisions look faintly like animation). A score by Georges Auric that incorporates elements of classical and jazz gives the movie an appealing rhythm.

For the finale, Picasso tells Clouzot that he wants to work on something more ambitious, and, after he fusses with the face and coloring of a goat, the film switches to CinemaScope and watches as the painter toys with the facial expressions and abdominal contours of a nude woman, among other sights. The secret mechanism undergirding Picasso’s creativity remains a mystery by the movie’s end, but watching his handiwork is still enthralling.

‘Room 237’ (2013)

Forget Picasso. Is it possible to get inside Stanley Kubrick’s head? Rodney Ascher’s documentary dives deeply into various fan theories surrounding Kubrick’s “The Shining” (1980). Kubrick’s reputation for total control means that absolutely nothing in his movies should be regarded as accidental (even if it is), and “The Shining” opened near the start of a revolution in film watching. Home video suddenly made it possible for obsessives to pore over every image with relative ease.

The theorists themselves narrate, and Ascher, who did his own editing, creates a vortex-like atmosphere that makes it hard not to get hooked on what they’re saying, no matter how ludicrous. They have some persuasive ideas: Passages suggesting that Kubrick conceived the film as an allegory for genocide — filling it with allusions to the Holocaust and to the slaughter of Native Americans — are convincing. Fans invested in the Minotaur and labyrinth imagery, or who attempt to map the floor plan of the Overlook Hotel, or who discover strange connections when they play the movie overlaid backward and forward simultaneously, have at least done interesting spadework. And still other notions here — like the conspiracy theory that the moon-landing footage was faked with Kubrick’s help, and that “The Shining” was his attempt to reveal it to the public — are the sort of pernicious idiocy that ought to be confined to the most obscure pockets of Reddit. (The movie opens with a long legal disclaimer stating that none of the views in it reflect those of Kubrick or the other “Shining” filmmakers.)

That Ascher’s subsequent paranoia-thons (“The Nightmare,” “A Glitch in the Matrix”) have gotten mired in that sort of speciousness suggests he hasn’t yet found another subject as rich or complex as Kubrick. But while “Room 237” may piggyback off another filmmaker’s genius, it proves yet again that “The Shining” is an endlessly fun puzzle to solve.

‘Three Minutes: A Lengthening’ (2022)

Stream it on Hulu and Kanopy. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Google Play and Vudu.

Bianca Stigter’s documentary takes a close reading of a very different sort of film. It centers on three minutes of footage shot in August 1938 by David Kurtz, who had arrived in the United States when he was 4, but was that summer back in Europe touring the continent. He shot those three minutes of footage in his hometown, Nasielsk, Poland, where, according to the documentary, fewer than 100 of the 3,000 Jewish residents would survive the Holocaust.

Stigter, whose book “Atlas of an Occupied City (Amsterdam 1940-1945)” served as the basis for a recent, Cannes-premiered documentary from her husband, the director Steve McQueen, shows the three minutes in full at the beginning and then spends the rest of “A Lengthening” examining them in minute detail, sometimes frame by frame. Taking cues from a book by Glenn Kurtz, David Kurtz’s grandson, who elaborates in voice-over, the documentary explains how the location and even some of the people in the footage were identified. (Eleven, to be precise — out of more than 150 people in the footage. Stigter at one point arrays all the subjects’ faces in a mosaic.)

Maurice Chandler, of the two people in the footage whom Glenn Kurtz was able to locate still living, says that cameras like David Kurtz’s were rare, which explains why different social groups in the town that rarely mingled had all clamored to greet him. Every element of every image of the footage, from the clothes that women are wearing to the shadows on buildings to the shapes of out-of-focus letters, offers a potential clue. Stigter, whose perspective is voiced by the narrator, Helena Bonham Carter, is also concerned with just how much the images leave unseen. During testimony about the December 1939 roundup of Jews in Nasielsk, she slowly zooms in on a frozen image of the calm town square where it happened. Glenn Kurtz says that most contemporary viewers of the footage see it differently from how survivors do, because survivors can see what’s beyond the frame.