Barry has always been a tough show to get a handle on. Seemingly hellbent on staying three steps ahead of the viewer, the show positioned itself as Breaking Bad speedball. Ostensibly, a half-hour comedy about a disgraced Afghanistan veteran who becomes a hitman when he realizes his murderous set of skills has no real use in modern life. Well, outside of killing people for money. Still, Barry learns that maybe he could express some of his rage, PTSD, and the wide array of emotional problems that neither he nor the country that set him to war seems capable of solving through theater. Imagine what this country could be with an arts program as robust as its military-industrial complex. But it’s not. In the country where this recap is being written, Barry yells “Gun!” at a Walmart clerk, and neither she nor anyone in this bustling store of shoppers, clerks, security guards, and likely fellow veterans does a thing about it. Barry straps on two military-grade assault rifles, holsters his pistols, and walks purposefully through the automatic doors to his car unbothered by the heavy artillery attached to his person. Like the gangster who rides leisurely to NoHo Hank’s crime utopia earlier in the season, violence seemingly doesn’t register with people in the world of Barry.

Part of that, as the episode unravels, is the absolute hunger we as a society have for a clean narrative. This happened because of that. It’s been Barry’s guiding light for the last four seasons as one bad decision begets another, and so on, until NoHo Hank clutches the bronze hand of the love of his life, his last breath heard only by the few barely living soldiers bleeding out around him. Sure, now, Livewire sees the value of human life as he pleads with Groove Tube to wake up. But it’s the narrative that compels us, right? Why did Barry do all this? Why did Fuches? Hank? The answer to why men do the things that they do is innocuous, an everyday evil, a banal response from Fuches: “I was a man with no heart.” It’s a charge that fits the bill for basically every man on this show.

Barry has long been a show about a bunch of Hollywood assholes who refuse to accept accountability for their actions. That it came out in the middle of the first wave of #MeToo allegations makes its satire a little overblown and on the nose. In a world where no one cares that a wanted, armed killer is walking through a department store with a face like Barry’s and the means to do it, the blind eye we all turn to these mundane evils is as much a part of the show’s narrative as anything. Of course, Barry wants us to have fun with this idea too. It is funny, says the critic who has been enjoying the show’s descent into darkness while still finding the bright spots of humor the show’s best attribute. How fun are we supposed to have with this stuff? What’s so funny about all this killing anyway? Through Barry’s perspective, we always had a detached view of the subject, allowing moments of horror to happen casually.

In Barry’s final half hour, nothing’s really that funny until the narrative takes over. That narrative isn’t the one the show has been telling this whole time, the one with detours in the middle of nowhere or Hank’s NoHo hourglass. It’s the one that the people inside the world of Barry concocted to make sense of it. What do they do to the “Barry Berkman Story,” the tale of a lost veteran trying to understand himself through art and murder? They turn it into a Jack Reacher movie, an actioneer that could be charitably called “Paul Schrader lite.” After all, the only narrative left is the one where Barry is a hero, buried at Arlington Cemetery with full accommodations. I mused earlier this week about how I couldn’t see this show having its Taxi Driver ending, where he ends up the hero. And, aside from the whole getting shot in the forehead thing, that’s what happens. By the end of Barry, Barry’s a hero to the world and his son. That was God’s plan for Mr. Berkman.

And God answers Barry’s wishes. When the episode starts, we hear the same discordant sound cue we left off on last week. Hoping to draw that same line of intensity from the previous installment, we cut to The Raven, sitting pretty in his palatial tub when Hank calls with a deal. He’s got Sally and John, but Fuches is only interested in the latter. He’s barely interested in Barry.

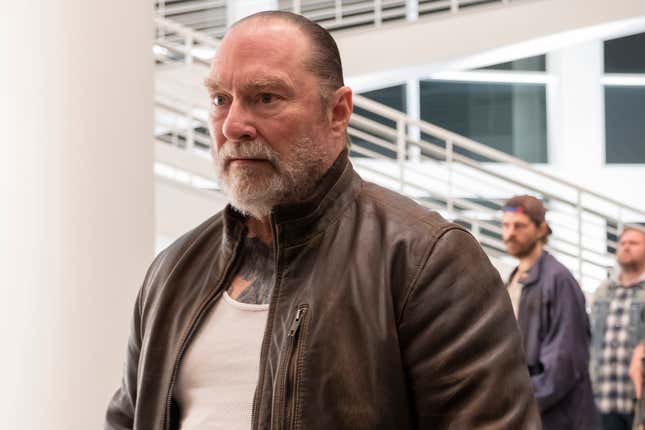

While “The Mask Collector” has a very specific and stupid meaning come the episode’s end, it could very well apply to Fuches here. When Raven arrives at NoHobal to face off with Hank’s spectrum of goons that create a color profile that would make Roy G. Biv proud, he tells Hank that he had a come to Jesus moment in prison. After daily beatings, he realized exactly who he was: the aforementioned man with no heart. He sees the same in Hank. And while he calls Hank for what he is, a snake, he also demands that he drop the act, the denial that fuels Hank’s continued success as a businessman. And it crushes Hank.

Mostly told through a series of close-ups, the episode really gets a look at these characters’ faces, the lines, and the weariness. For years, Barry has presented masks of its characters as they pretend and insist they’re good people. Sometimes that mask is obscured through performance—this is a show about acting, after all. This is an episode about unmasking and what it takes to do that. Unsurprisingly, it’s Sally who gives the straight story first. In a tight profile with the back of John’s head hanging in the frame, Sally comes clean, telling John that she and Barry are fugitives and that she is a killer. She murdered a man, and it’s the first time she admitted it on the show, and God bless Sarah Goldberg, who looks as though 600 pounds had been slowly lifted from her chest, as she finally takes off the Emily mask and shows him Sally. He hugs her for the first time, and the two, in her honesty, share the second loving moment between child and mother on the show. It’s a moment of redemption for Sally and one that sets the course for her behavior in the rest of the episode as she becomes a more decisive and confident person. All it took was living through a firefight.

Hank isn’t so forthcoming. The close-ups between Fuches and Hank in their showdown were the moment when I missed Barry the most. How many shows are giving Stephen Root and Anthony Carrigan these lingering long takes to stare at each other, manipulating, crying, laughing, and saying everything without saying it? As with Sally’s mournful admission, Hader really lets the actor work while he simply captures their stunning performances with the camera. And they are stunning performances. Consider how far Carrigan has gone from season one, when he was mostly known for sending Bitmoji that undersell the danger they’re constantly in. Here, he’s a quivering mess, clearly and utterly devastated by Cristabol’s murder, with Fuches forcing him to take accountability, and he can’t. What follows is a quick firefight and one hilariously deadpan grenade that ends the conversation before it can happen.

As the scene comes to a close, with Hank’s last breath escaping his body, as dramatic as ever this one, Barry arrives with his arsenal just in time to catch Fuches and John on the way out the door. In the end, Fuches saved John and delivered him to Barry. Again, another pair of close-ups seemingly tells the audience that there’s an understanding between them now. In exchange for John’s safety, Fuches is no longer on the list. No words were exchanged. Fuches disappears into the night.

So Barry, Sally, and John escape the clutches of NoHo Hank, more or less, unscathed. Of course, John is fucked psychologically anyway because of who his parents are, but at least the better angles of Barry’s writers’ room won out. John, after all, is alive. Still, now with her admission to John on the table, Sally shows off her inner Fuches and pushes Barry to turn himself in.

Barry’s religion has really become the last level of evading accountability. Who is he to judge himself? Only the Lord can do that. What’s more, he was ready to exchange his life for John’s safety, and considering God spared Barry, maybe they should just continue on their awful way, regroup and find a new place to hide out for the rest of their lives. However, the new and improved assertive Sally has been reading about Cousineau’s situation, how the cops have pinned all of Barry’s crimes on him, and how unfair all that is. She pushes Barry to turn himself in, and when he refuses, she turns her back to him. The next morning, she absconds with John, leaving Barry to fend for himself.

Like many series finales, Barry’s has distinct sections, a few scenes for audiences to say goodbye to specific characters and versions of them. First, we said goodbye to Fuches and Hank, Barry’s crime world. The next one, though, is more personal, and like another season finale, it has a very abrupt finish. Barry arrives at Cousineau’s ready to do the right thing. Catching Tom as he sneaks out the door, Barry walks into Cousineau’s as his old teacher takes out Rip Torn’s pistol, a Chekov’s gun many times over, that has been the subject of one of Barry’s greatest sound gags and the source of one of its greatest cliffhangers. The latter was brilliantly memorialized by a Los Angeles Times headline in the episode. As Barry sits on the couch, he tells Tom to call the cops and begins to cry. It will be our last close-up of Bill Hader before Cousineau shoots him in the chest and head. It’s a stunning shot from the acting teacher, who must’ve done some target practice in Israel. But it seals the deal on Barry’s legacy.

The episode cuts to black, á la The Sopranos, immediately after the shot to the head. It’s so abrupt that for half a second, it felt like the real thing. Would Hader be so overt to court comparisons to television’s most prestigious prestige show? No, we’d fade back in and see Cousineau sit on his couch, seemingly serene. His nightmare is both over and just beginning because he’s going to jail, and to the rest of the world, he’s the masterful kingpin behind all these murders.

But that’s not all. In a move that can only be described as for the Our Town heads in the audience, the show does another time jump, taking us several years down the line to an older, wiser, and yes, slightly more confident Sally Reed. Now a theater teacher lapping applause for a well-received adaptation of Our Town, she beams with pride as she accepts her flowers. Outside, she quickly shoots down a date and lets John go sleep over at a friend’s house. She doesn’t overthink it. All the bad men are gone. She’s no longer seeing Shane’s bleeding eye in the cold light of day. Sally seems content without Barry in her life. Though, the way she looks at the flowers on her ride home does have a reminder of the flowers that Barry used to bring—er, the ones she asked him to bring her on the set of “Joplin.” There’s a sadness to her as she stares at the empty passenger seat, but it’s probably better than her life with Barry.

It’s at this point in a very short episode of television (relatively speaking) that it starts to feel a little like Hader is spinning his wheels. How is this all going to wrap up? It’s starting to feel a little anti-climactic, as if there’s even supposed to be some grand unified Barry theory that makes sense of everything we’ve seen over the last four years.

In the end, there is. It’s all about narrative. It’s all about how we consume, venerate, and celebrate violence and the violent people in society. John (now played by Hader’s fellow It alumni Jaeden Martell) and his friend sit down to watch “The Mask Collector,” a sub-Lifetime adaptation of the Barry TV show. To pull another comparison to the Sopranos, its fidelity to show is very “Cleaver,” a bloody, cheap, and sensationalized account of the reality we’ve seen on TV. Moreover, it turns Barry into the hero of the story, the story that John’s heard before. It’s the story that, as Clark, Barry told John on the steps of their home. Poor Barry was manipulated by Cousineau and forced to do unspeakable things before saving his family and dying in a final confrontation. After years of telling people he’s a good person, Barry is the hero, a lost vet trying to understand himself and being taken advantage of by a capable older man.

Through that story, Barry escapes accountability forever. Print the legend of Barry, and that’s all everyone will ever know. It doesn’t matter that he was a man with no heart. It doesn’t matter about the truth. It doesn’t matter that Barry was a cruel, despicable human being who often killed because he didn’t have the skills for anything else. It’s a narrative that we can understand. That’s really what Barry was about. Violence is chaos, and in the process of making sense of it, we assign good guys and bad guys—a good guy with a gun takes out a bad guy with a gun.

Forgiveness needs to be earned, Hank reminds us in season three. Fuches seemingly earned it when he delivered John. Sally earned it when she told John the truth. Barry came ever so close to starting a path to redemption—well, sort of, Barry can’t really be redeemed—but it was too late. His crimes have already spawned another violent killer because that’s what violence does; it starts a cycle of violence, one we’ve seen play out numerous times on the show, particularly last season when the families of Barry’s victims disastrously tried and failed to get revenge.

Who knows what the secret knowledge of having seen “The Mask Collector” will mean for John. Maybe he’ll follow in his father’s footsteps. Or maybe he’ll be an actor like his mom. In its final frame, Barry asks us to consider what effect watching violence has on us as viewers. With John’s slight smile of relief, the mayhem that Barry presented is now fodder for mindless entertainment that belittle the real victims. At least Ryan Maddison’s father, who killed himself after driving Barry to the hospital, isn’t alive to see what Hollywood has made of his son and his son’s killer.

For all the darkness this season, it feels fair to ask one last time: Was Barry a comedy? Ultimately, it’s hard to laugh at the show because it started to look a lot like real life. The crimes on Barry aren’t so dissimilar from what we in the U.S. see on the news every day. In a country where multiple mass shootings happen daily, and domestic gunfire is a leading cause of death, what on this show is exaggerated? It takes Hank combing the ACME catalog and going full Looney Tunes to get a laugh out of this stuff. Over its short run, Barry became a show about the ways we perceive, mythologize, and try to shed ourselves of the responsibility of the violence around us. The ways we turn our heads from it and try to process it. Barry treated its characters as bad guys in a society that celebrates them. Barry was a bad guy with no heart, a product of a violent culture that gave him nothing but a gun and told him to kill. Now, he’s a hero. Tricky legacies.

Stray observations

- “I figured out my dad bought my house with drug money… So he shot me.”

- I’m starting a campaign to have the national anthem changed to a Bill Hader yelling “Guns!”

- Fred Melamed creeping out of Cousineau’s house was one of the few laughs tonight, but it was a hardy one.

- CeCe Peniston’s “Finally” gets a hell of a needle drop when Barry marches to the gun counter.

- I can’t say how happy I am that Hader gave us so much Fuches and Hank business last week. As great as it has been to watch Carrigan really stretch out, there’s nothing quite like watching Hank figure out or escape a murder.

- Alas, no more Larry Chowder from this show. I was really hoping that we’d get a taste of Chowder in a trailer when John started watching “The Mask Collector.”

- It would’ve been easy for “The Mask Collector” to go overboard with the Cousineau character, but I thought Michael Cumpsty found a real solid balance. It must’ve been hard not to go even harder with it. His restraint is appreciated.

- Thank you so much for reading our Barry recaps this season, and thank you for the great discussion in the comments, which always challenged my thinking on the show. It was a weird and difficult season, but more than other shows, I think Barry committed to its characters by not redeeming them, ultimately dragging the show down where it needed to be. It’s honest, in a way, about the type of show it is because none of this should really be all that funny anyway. That Barry could be so many things and do it in a half hour is an incredible achievement and a rewarding watch, even if it made us queasy sometimes.