The most powerful moments in the revised version of “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” Anna Deavere Smith’s landmark drama about the uprising that followed the verdict in the savage police beating case of Rodney King, involve video of horrendous violence.

When footage of officers brutally pummeling King is shown, the audience at the Mark Taper Forum, where the play had its premiere 30 years ago, is overcome with silence. The video is well known, having been part of the national media coverage at the time, but history has only added to the weight of what we’re watching.

Harrowing video of unarmed Black men being assaulted by officers has become an all-too-common tragic reality. Cellphone, bodycam and surveillance videos have turned us all into eyewitnesses of deadly police brutality.

Video can’t tell the whole story. Where there’s a camera viewpoint, there will always be debate about what lies outside of the frame. But the presentation compels theatergoers to see violence in all its horrific bodily specificity — to take in the inhumanity of the perpetrators and the dehumanization of the victims.

The footage of a prone Rodney King being assailed by batons isn’t the only video that’s shown in this new production of “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992.” Grainy surveillance footage of the shooting of Latasha Harlins, a 15-year-old Black girl, by Soon Ja Du, a Korean American convenience store owner who thought she was stealing an orange juice, is also included.

This incident, coming on the heels of the videotaped King beating, contributed to the civil unrest that resulted in approximately $1 billion in damages. (Korean American-owned businesses were disproportionately affected). More than 50 people died, thousands were injured and thousands more were arrested (a majority of whom were Latino, mostly young men).

The production also includes raw footage of the attack of Reginald Denny, the white truck driver who was pulled from his vehicle by a group of Black men and viciously beaten in an incident that became a symbol of the explosive rage and destruction that seized the city for days. The effect of these videos overpowers thought, but the production insists that we not only bear witness to what is in the frame but also contemplate what’s beyond it. (In the example of Denny, this includes information about the rescue by Black residents who risked their lives to save his.)

In “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” Smith explores causes and consequences of events that are too momentous to have simple explanations. What is most radical about the play, then and now, is its refusal to dispense answers. Smith doesn’t editorialize. The only side she’s on is the side of humanity.

Her theatrical method is to listen to voices that likely would have had trouble hearing one another. Her play, composed of excerpts from the more than 300 interviews she conducted on the ground in L.A. in the year following the uprising, is a kind of talking mosaic, in which clashing perspectives can peacefully coexist.

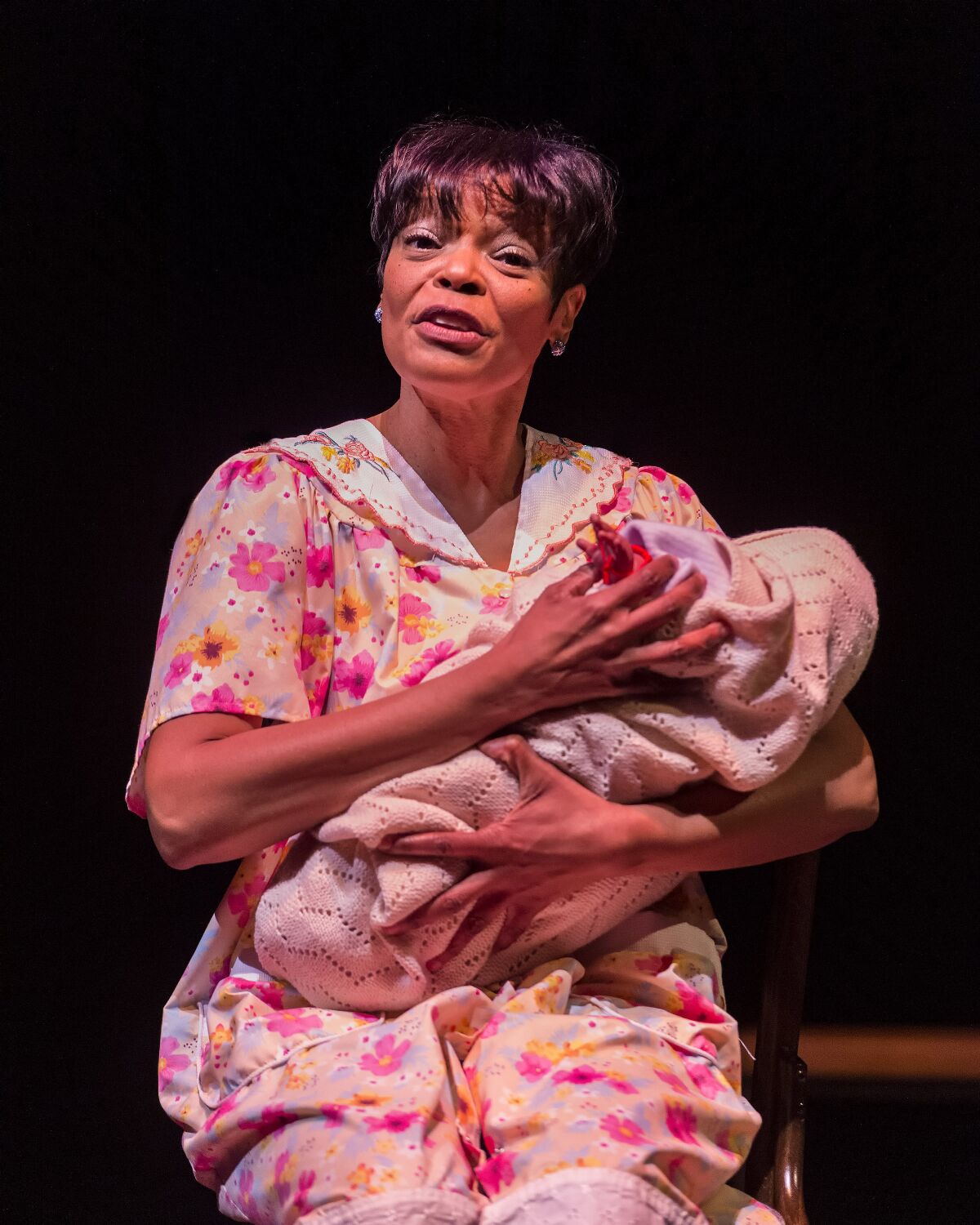

Jeanne Sakata in “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992” at the Mark Taper Forum.

(Craig Schwartz)

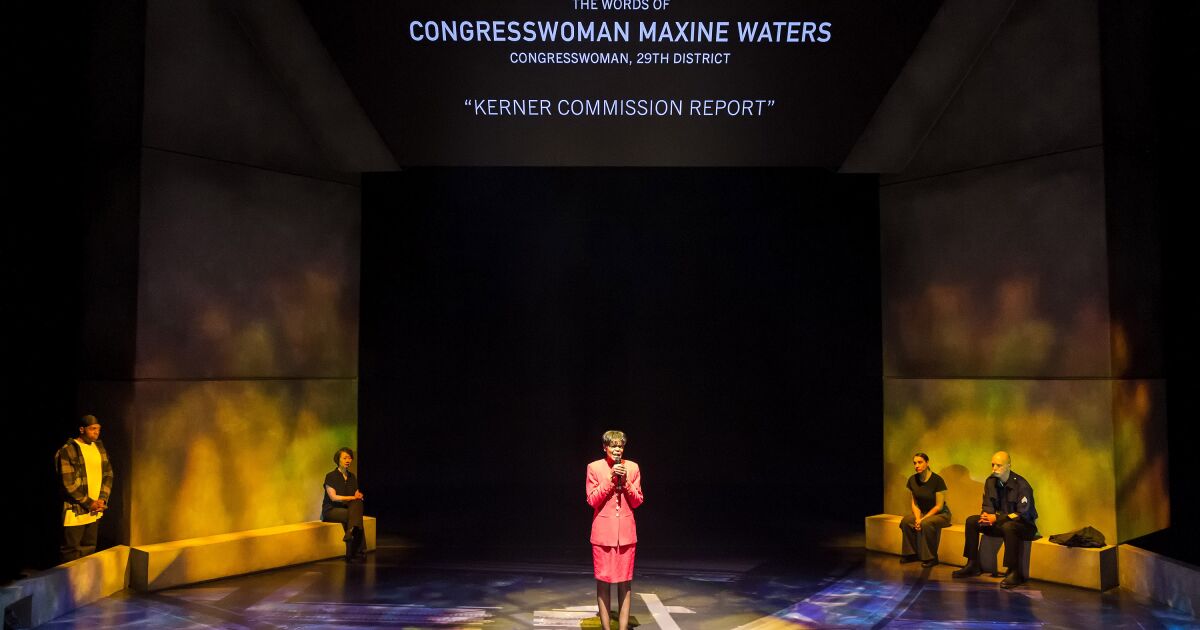

The play, originally a solo work performed by Smith herself, has had many iterations since its Taper premiere in 1993, including an abridged 2000 film adaptation. This new version, directed by Gregg T. Daniel, has been reconceived for a five-person cast.

The actors (Hugo Armstrong, Lovensky Jean-Baptiste, Lisa Reneé Pitts, Jeanne Sakata, Sabina Zúñiga Varela) take turns animating the various speakers. The diversity of the ensemble informs the range of characters, but the theatrical effect was blunted by the somewhat shaky command of the script by a few of the actors at Sunday’s press performance, which had been delayed a few days to give the actors more time, according to a Center Theatre Group representative.

I was quite excited about the prospect of seeing “Twilight” performed by other talents. But the experience only enhanced my understanding of its power as a solo work and the special qualities that Smith brought to it as a writer-performer.

I missed above all the prodigious moral stature of Smith’s stage presence, which shadowed the community of voices channeling through her. She found the theatrical contours of other people’s humanity in her own. The interviewees’ race, class, gender and point of view were no obstacles for her. This elasticity of acting is a key part of the play’s vision, offering implicit proof that the divisions among us are bridgeable. Daniel’s production honors this to a degree, but the ensemble casting attenuates the effect.

Smith’s handling of language was also, I now see, instrumental to how “Twilight” works. The figures in the play become known through their speech acts. They are in conversation with an interviewer and should not be treated as though they are Chekhovian characters lost in their own inner lives. The rhetorical dimension of their presences must be prioritized. Muttering subtext is beside the point.

Lisa Reneé Pitts in “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992” at Mark Taper Forum.

(Craig Schwartz)

Pitts, who brings to life several key Black politicians and activists (including Congresswoman Maxine Waters), is the most adept of the cast members at skillfully deploying oratory. Despite some patches of unsteadiness, Sakata has moments of a piercing authenticity — devastating pleas of understanding from marginalized immigrant corners.

Yee Eun Nam’s projection design is the most dynamic aspect of the staging. Efren Delgadillo Jr.’s scenic design wisely opts for unencumbered sets, but the movement of the actors has a revolving door quality that can seem pedestrian, even when a role is performed by more than one cast member.

But this revival comes to us at a time of protracted crisis, offering us invaluable historical perspective on our own combustible condition. The play is updated for an audience that is still grappling with the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the protest movement and national reckoning that followed in its wake.

The words of former L.A. Times journalist Héctor Tobar shed light on how the uprising was larger than one sociological event. He names the “Latino poverty riot” as what happened in the “vacuum” that was created by the breakdown of order. Tobar’s wisdom is invited back near the end of the play to link the George Floyd and Rodney King videos as catalysts for the awakening of consciousness “through the public dramatizations of Black suffering.”

The stubborn persistence of institutional racism, police violence, a bifurcated justice system and economic inequality might suggest resignation and a reason to despair. But “Twilight” connects us to the long thread of struggle. It asks us to do something that has become even more challenging in our digitally siloed world — make room for another truth, no matter how divergent from our own.

‘Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992’

Where: Mark Taper Forum, 135 N. Grand Ave, L.A.

When: 8 p.m. Tuesdays-Fridays, 2:30 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 and 6:30 p.m. Sundays. Ends April 9. (Call for exceptions.)

Tickets: $35-$120 (subject to change)

Info: (213) 628-2772 or centertheatregroup.org

Running time: 2 hours and 35 minutes with one intermission

COVID protocol: Check centertheatregroup.org/safety for current and updated information.