In the aftermath of World War II, in a changed world, story ballet seemed to have little future as a credible art form in which a narrative evening-length ballet could be created to a lasting new score. Prokofiev’s “Cinderella,” which had its premiere in November 1945 at the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow, was the last new major story ballet to enter the repertory.

Ambitious attempts in mid-1950s London — notably “Prince of the Pagodas” and “Undine,” with exceptional scores by Benjamin Britten and Hans Werner Henze, respectively — “didn’t,” as the British press sniffed, “quite come off.” Instead, the fashion became for new story ballets to be created around old music.

Yet story ballet did, in fact, enjoy an exceptional postwar popularity in the West. “The Nutcracker” was only performed completely in the U.S. on Christmas Eve 1944, by the San Francisco Ballet, making it the holiday phenomenon that it has become. Meanwhile, choreographers of all stripes have never ceased reimagining the classics, the revivals of which keep many ballet companies alive. As recently as February, the touring French avant-garde company Ballet Preljocaj brought its strikingly effective “Swan Lake” to Santa Barbara, updated to evoke a modern environmental catastrophe.

But choreographer Christopher Wheeldon and composer Joby Talbot have been making brand-new, large-scale story ballet once again a popular sensation. Beginning with their hit “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” by the Royal Ballet in 2011, the team followed up with “The Winter’s Tale” three years later. Last June, the Royal Ballet unveiled their latest collaboration: “Like Water for Chocolate,” a co-production with American Ballet Theatre. Wednesday night, ABT brought the new ballet to Segerstrom Center for its U.S. premiere. In June, it will open ABT’s summer season in New York. It is said to be one of the most elaborate productions the 84-year-old company has staged.

The dancing bedazzles. The choreography is full of spectacle, and the production is effects-rich. The familiar narrative from Mexican novelist Laura Esquivel’s 1989 bestseller and the 1992 film serves up sentiment without embarrassment. Talbot’s orchestral score tells you how to feel and suggests movement possibilities for the dancers. The sheer scale of theatrical engineering is astonishing.

Everything works as intended. And everything should work, given that Wheeldon and Talbot rely more on expertise than novelty. There is little, if anything, outside of the technical virtuosity on display that feels new to either Esquivel or dance. There is no attempt at the fresh perspective of, say, American rapper Common’s acclaimed 2000 album, “Like Water for Chocolate,” which he has said was influenced by the title of Esquivel’s work. But that is not the point.

Wheeldon and Talbot take considerable pains to get the milieu of the novel right. ABT introduced the performance Wednesday with a brief promo film featuring Esquivel and Mexican conductor and musical consultant Alondra de la Parra extolling the project. Mexican architect Luis Barragán is the inspiration for Bob Crowley’s impeccable decor. (Sets based on the work of artists seems to be in vogue, including the sets influenced by Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi that grace Los Angeles Opera’s current production of “Pelléas et Mélisande.”)

Talbot’s score features elements of traditional Mexican dance and song, as does Wheeldon’s choreography, gloriously so in big numbers. The guitar and ocarina join the orchestra — the Pacific Symphony, conducted by David LaMarche, replacing de la Parra, who couldn’t travel because of an ear infection.

Catherine Hurlin (Gertrudis) in Christopher Wheeldon’s “Like Water for Chocolate.”

(Marty Sohl / American Ballet Theatre)

But for all the efforts at authenticity, this is little more than the fact that ballet loves locale. Talbot’s score, which goes in for Hollywood-style climaxes, sounds more like a generic film or Broadway score.

Wheeldon’s attempts to translate the essence of Mexican cooking into dance is far more interesting. Esquivel introduces each chapter of her novel, which takes place in the early 20th century, with a recipe. Tita, the novel’s protagonist, is forced to devote her life to tending to her domineering mother, Elena, the role expected of the youngest daughter. In her frustration, Tita learns to express herself, as well as her forbidden love for Pedro, through her extraordinary cooking.

Wheeldon accepts that challenge with convincing solos. On opening night, Cassandra Trenary’s Tita was danced with exquisite emotional reserve, yet capable of releasing unending passion with Herman Cornejo’s Pedro or contending with Christine Shevchenko’s sternly commanding Mama Elena.

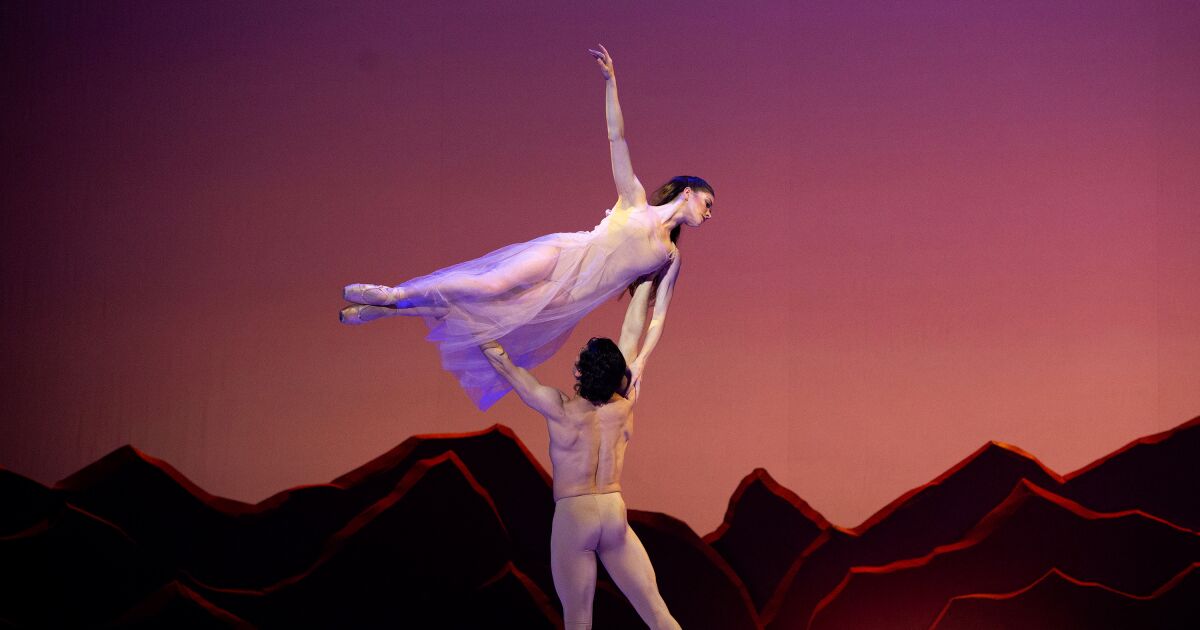

Cassandra Trenary and Herman Cornejo of ABT.

(Marty Sohl / American Ballet Theatre)

As a story ballet, “Like Water for Chocolate” functions almost like a French grand opera. There is a lot of plot, which in dance requires a lot of narrative mime; most of it, and its music, is forgettable. One thing leads into another, though, with an impressive technical smoothness that allows fantasy — marvelously so, when the ghost of Elena appears — and reality to intersect with a naturalism that reveals the real genius of ballet. It would take several viewings to catch all the detailed translations Wheeldon makes in his movement language to capture character and incident.

In the end, it is show business that wins out, as when Catherine Hurlin’s Gertrudis, Tita’s sister who joins the Revolution, leaps with exuberant lyrical abandon. Hee Seo has a more thankless task as Tita’s less-lively sister Rosaura, who marries Pedro, but she readily wins our sympathy. Tita weds the affable Dr. John Brown while continuing to carry a flame for Pedro. We’re meant to side with true love; Cory Stearns’ appealing portrayal as John makes that no sure thing.

The cast is large, filled with any number of minor characters who grab momentary attention. The ABT corps offers heaps of pleasures. The wow moments keep coming.

The ballet ends with a soaring, breathtakingly beautiful pas de deux for Tita and Pedro. It is made to leave you with goosebumps. To not give it a standing ovation is to be hardhearted. Under it all, though, as one schmaltzy cliché follows another, this becomes more the glorification of beauty than the real thing.

As you enter Segerstrom, you may not notice Richard Lippold’s grand sculpture “Fire Bird.” Once while working on a film with the sculptor, composer John Cage said to Lippold, “Oh, Richard, you have a beautiful mind. It’s time you got rid of it.”

He did, the reward being that his “Fire Bird” seems to elevate an otherwise uninspired building without needing to catch your eye. The same might go for some of the extravagant signaling of beauty in “Like Water for Chocolate” that serves to manipulate the observer. The ballet’s marvels need no help.

‘Like Water for Chocolate’

Where: Segerstrom Hall, 600 Town Center Drive, Costa Mesa

When: Through April 2. Check website for dates, times and casts.

Pricing: $29-$250

Running time: Approximately 2 hours, 40 minutes, including two intermissions.

Info: (714) 556-2787 or scfta.org