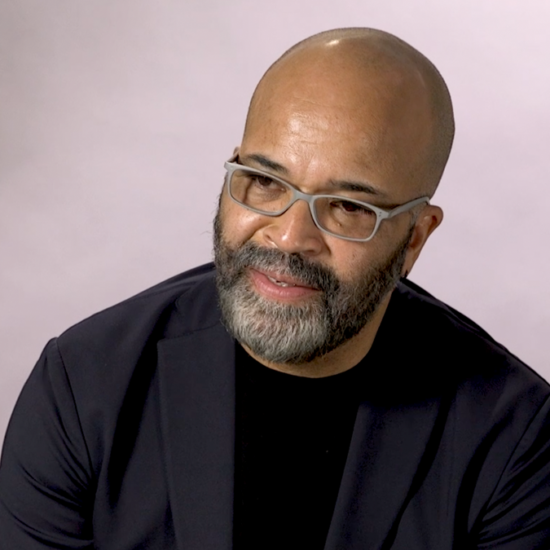

Kate Lear is a writer, arts advocate and proud Board Chair of Ballet Hispánico. She is also the daughter of television writer and producer Norman Lear. She shares the wit and wisdom of her father in celebration of his 100th birthday.

I am the daughter of an extraordinary man, and I have been a loving observer of his life for more than six decades. On July 27th, 2022, he turns 100! As the second of his six children, I marvel not only that he has lived to be 100, but that he has enjoyed the heck out of getting here, learning just as much from his challenges as from his victories. So, what are his secrets?

To reach 100 you need many things, and the most obvious is good luck and lots of it. But to me, Norman Lear’s longevity has just as much to do with his in-born optimism. This is a man who goes to bed each night dreaming of the cup of coffee he will have in the morning, who has lived a life in which each meal magically turns out to be better than the one before (“this is the best pasta I’ve ever had!”), and who has said, many times, that he doesn’t want to wake up the day that he doesn’t have hope.

But his optimism just might be eclipsed by his profound interest in people and in the world. My father is the most outward-looking person I have ever known. He has never met a person he didn’t find fascinating. And because of this, as he grew older, his world expanded rather than contracted. What other 99-year-old is the last person to leave a party, or has an overall deal with Sony Pictures Entertainment? My father is a fortunate person, to be sure. But he is also a person who sees the opportunity in each day to meet someone new, eat something new, discover something new. There is a childlike innocence and curiosity that are as present in him at 100 as they were at 10.

There are two pieces of philosophy that I believe have helped my father continue to live a life of action and consequence.

One is a quote attributed to Rabbi Simcha Bunom: “Every person should have two pockets. In one pocket should be a piece of paper saying: ‘I am but dust and ashes.’ In the other pocket should be a piece of paper saying: ‘For my sake was the world created.’” I think he finds comfort in the last words because they affirm his instinct to follow his passions: to fight for his country as a radio operator in World War II, to fight for “All In The Family” to get on the air because he figured if he thought it was funny, so would America, to fight for our democracy by creating People For The American Way, and to do all of those things without apology. But it is the first part of the saying, about the importance of humility, that cautioned him never to get too comfortable, and that acts as a motivating factor even today.

The other piece of philosophy is his own. The doctrine of Norman Lear is “over, next.” My father will tell anyone who will listen, “when something is over, it is over and it’s on to next. And if there were a hammock in between, that is the best description, that I know of, of living in the moment.” Believe me, I didn’t always love the “over, next” life. When you are a teenager and your vacation is about to end, the last thing you want to hear is your father ebulliently saying those words. But I have learned that this piece of wisdom has enabled him to move past the darker chapters of his life and remain exhilarated about what lies ahead. My father recently said, “in thinking about death I don’t mind the going, it’s the leaving that is the problem for me.” After all, who would want to leave when tomorrow could bring a new friendship, the taste of a new brand of potato chip, or a bit of news from a grandchild. My father’s fascination with his fellow human beings and his hunger for all that our world has to offer has moved him ever forward. And for that both he—and the rest of us—are blessed.