When an interviewer asked Joshua Abrams how he tends to start writing a new song, he demurred: “Our process is one of continuance.” The Chicago composer and bandleader’s music, through the conduit of his ever-expanding ensemble Natural Information Society, feels as if it exists in a state of perpetual evolution, just beyond the range of human perception. Performances can take on the air of a ritualistic summoning. When Abrams convenes his band, the first notes glint like light in the crack between our world, with its strict laws of temporal-spatial continuity, and the one in which the music has existed, ceaselessly unspooling, for centuries.

While there is nothing explicitly spiritual about Natural Information Society’s output, the group draws on practices from around the world that facilitate transcendent experiences: Gnawa from North Africa, Hindustani classical, ecstatic jazz. The music of these traditions is frequently longform and often uses improvisation to expand upon a central scale or motif. Abrams threads together these sounds and structures, which have been reaffirmed and renewed by their tradition-bearers across hundreds of years, with the postmodern sensibilities of minimalist composition. The music’s timelessness is twofold: The techniques it employs to suspend time for the listener—mesmerizing repetition, nimble rhythmic interplay, buzzing drones—have unfathomably deep lineages themselves.

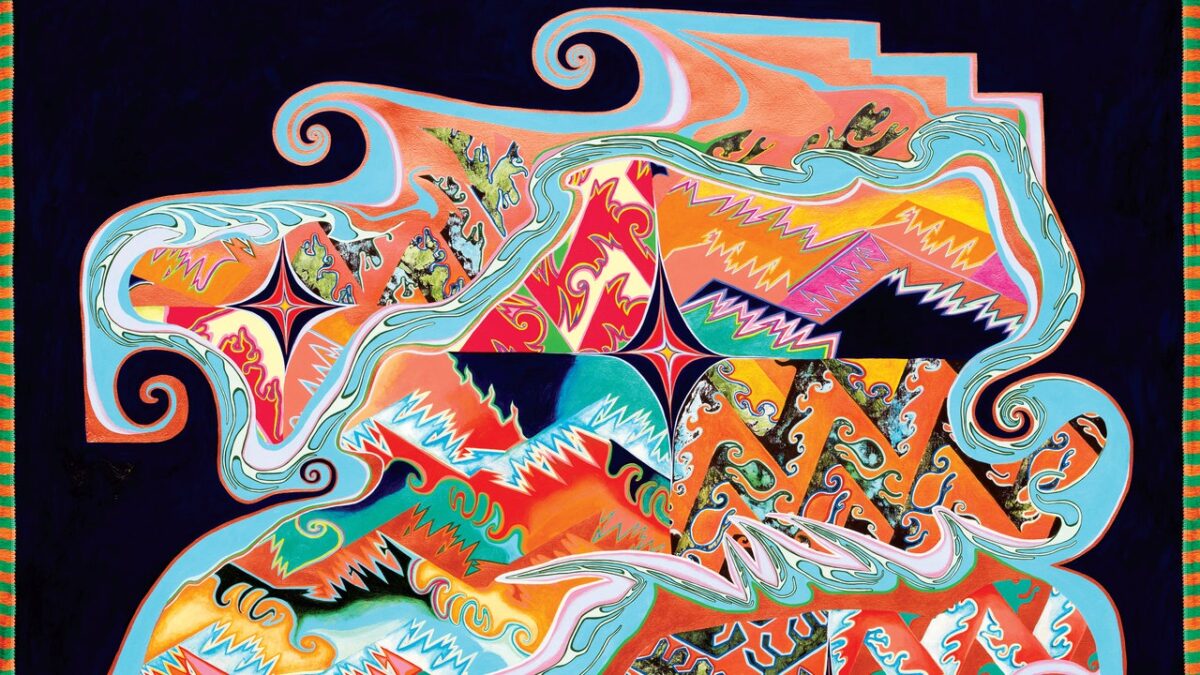

Natural Information Society’s latest album, Since Time Is Gravity, is a suite of vivid snapshots of eternity, a concept that should be oxymoronic but which feels completely natural in Abrams’ hands. He brings together players from across Chicago’s multifaceted improv community, including drummer and longtime collaborator Hamid Drake, multi-instrumentalist Ben LaMar Gay on cornet, saxophonist Nick Mazzarella, and elder statesman Ari Brown. Brown has played tenor sax alongside Coltrane sidemen McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones, as well as AACM pioneers Malachi Thompson, Famoudou Don Moye, and Kahil El’Zabar; his improvisations on bookending pieces “Moontide Chorus,” “Is,” and “Gravity” are informed by that lineage while maintaining a deeply individualistic sensibility, and his modal melodies walk a fine line between mystical ambiguity and conversational familiarity. These players are all steeped in jazz, but they are also students of the global histories that led to its development in the early 20th century.

Abrams’ guimbri provides the rhythmic and tonal center for each composition, including two solo pieces for the instrument, “Wane” and “Wax.” The guimbri is a three-stringed bass lute played by the Gnawa people of Morocco that Abrams first heard on The Trance of Seven Colors, by Maleem Mahmoud Ghania and Pharoah Sanders, key influences on his own work. Compared to Steve Reich, who invoked African styles within a Western classical context while claiming much of the credit, Abrams is more attuned to the traditions that have inspired him—and to the nature of his own borrowing. “I wondered if it was right to take it up,” he once admitted of the guimbri, but Drake, who recorded with Ghania, encouraged him to continue. Using the instrument’s unique tone, a bulbous snap of gut strings against stretched hide and buzzing metallic rings, Abrams traces concentric circles around ostinato figures, forming the frame onto which the tapestry of drums, percussion, horns, and strings is hung.