What is it about hit men at this year’s fall film festivals? No sooner had Bill Hader’s “Barry” finished its final season and landed a batch of Emmy nominations than David Fincher’s “The Killer,” starring Michael Fassbender as a contract killer going about his daily (and deadly) work, premiered at the Venice Film Festival to largely favorable notices on its way to a Netflix release. A few days later it was followed by Richard Linklater’s “Hit Man,” with Glen Powell as the titular assassin, which picked up more raves as it premiered in Venice, then went to Telluride and the Toronto International Film Festival.

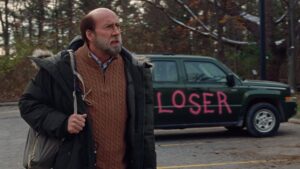

But before “Hit Man” will have its TIFF premiere on Monday, yet another hit man showed up on Sunday night in “Knox Goes Away,” which features Michael Keaton directing and starring as … well, you can figure out what the guy does for a living.

“Knox Goes Away,” though, isn’t just one of TIFF’s three hit-man flicks; it also belongs alongside “American Fiction” and the upcoming “Memory” as a film that deals with dementia. But the film is subtle, shuffling film-noir staples while remaining surprisingly low-key in a genre that often runs on blood and passion. There are plenty of both in the film, but Keaton is more interested in the brainpower that it takes to get past the blood and the passion, and that makes for an intriguing drama with a light touch or a comedy with some dark twists.

His character, John Knox, is a well-read and philosophically-minded hit man, which accounts for his nickname of Aristotle. (When we meet him, he’s reading Wilfrid Sellars’ “Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind” and doling out a weekly book from his library to his steady Thursday afternoon sex worker, played by “Cold War” star Joanna Kulig.)

Knox, it seems, has done well for himself in his chosen career, though to be fair he has destroyed his family in the process. But he soon gets some career ending news from his doctor: He has a form of untreatable dementia that moves incredibly fast and gives him “weeks, not months” of lucidity in which he can make arrangements.

“I’m sorry,” says the doctor after delivering this grim diagnosis.

“That’s OK, doc,” says Knox. “Even if I hated you for telling me, I’d forget soon enough.”

As the exchange suggests, “Knox Goes Away” is not a serious drama about dementia or about murdering people for a living. But it’s not a straight comedy, either. It’s a character study and what you might liken to a whodunit, though in this case it’s a howwillhedoit. That’s because, in short order, Knox botches a hit, accidentally killing his partner in the process, and receives a visit from his estranged son, Miles (James Marsden), who has himself accidentally (or sort of accidentally) killed the 32-year-old white supremacist who seduced his 16-year-old daughter online and then impregnated her.

Knox has to evade the cops who are investigating the murder he did commit while saving his son from the crime of passion that he committed. It doesn’t help that the cops, led by Detective Rale (Suzy Nakamura), figure out pretty quickly that Knox had something to do with the first murder and are bound to connect him to the second one before long.

The good thing is, Knox has always been a whiz at figuring stuff out and staying one step ahead of everybody. The bad thing is, it’s hard to do that when your dementia is getting worse every week. So, Knox makes an extensive checklist, shares it with his shaggy pal Xavier Crane (Al Pacino, attacking the role with leonine relish because that’s what he does), and gets to work.

The audience doesn’t know what’s on the list or whether it’s going to work (Xavier says it’s “a stupid plan”), but the whole point of “Knox Goes Away” is following the execution. The movie is a knowing film-noir riff that rarely misses a chance to trot out a noir trope, either in the way it’s shot (shadows everywhere – even brightly-lit rooms have horizontal blinds casting beams of light) or the way it’s scored (solo pianos, lone trumpets).

But even with all the noir touches, the film moves quickly. It’s shadowy but also breezy, which makes sense coming from an actor whose gone from the manic nutcase at the center of “Beetlejuice” and “Mr. Mom” to a maestro of restraint. Keaton conveys a lot without raising his voice and you never see him sweat. When Xavier hears about his condition he says, “I can’t think of anything worse, except maybe your pecker stops working,” Knox shrugs and mutters, “I’m actually looking forward to forgetting some things.”

There are times in “Knox Goes Away” when the shadows almost make Knox’s face look like a death mask, but he keeps plodding away and checking things off in his little notebook. He’s casual and he may be forgetful, but he’s also forceful, even as the weeks tick off and his minds starts to fail him. Keaton, the director, indulges in occasional flourishes of distortion to capture the character’s state of mind, but for the most part he trusts Keaton the actor, which is a wise move.

“Knox Goes Away” is a character study of a disappearing character or maybe a thriller that stays away from actual thrills. However you label the film, it’s low key but satisfying. It it – who could have guessed? – another good festival movie about a hit man.

“Knox Goes Away” is a sales title at TIFF.