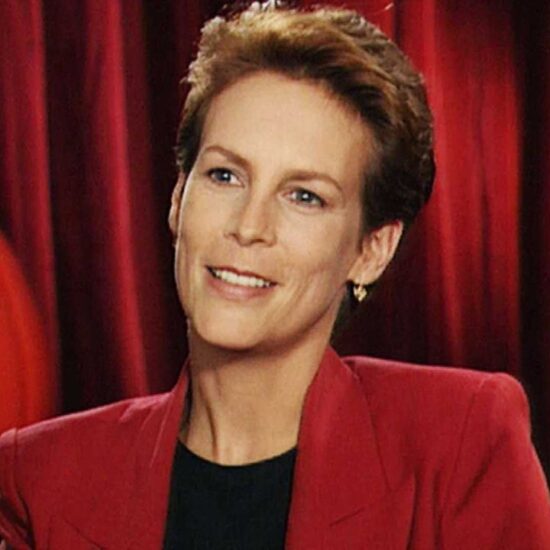

Opera is a sport. Its singers are athletes, and for those of us who love this sport, we often breathe for the singers when they miraculously deliver long stretches of music without taking a breath. I do it all the time in the opera house. I have never done it in the theater while watching a play – until I saw Jodie Comer in Suzie Miller’s solo play “Prima Facie,” which opened Sunday on Broadway at the Golden Theatre after its world premiere in the U.K. in 2019 and a production on the West End last year.

Comer is a superb athlete. “Prima Facie” runs 90 minutes, and in its first 15 minutes, it appears that this actor never takes a breath as she races at breakneck speed through her character’s background as a defense barrister for persons accused of sexual abuse. The extreme alacrity and force of Comer’s delivery is part aggression; she plays a very truculent defense lawyer named Tessa Ensler. It is also part compensation for the character being a woman born in the working-class. At Cambridge University, she had been surrounded by students, most of them male, to the manor born. She defends her fierce grilling of the plaintiff because that is her role as a defense lawyer. Tessa is a real professional.

“There’s blood in the water and I let the witness swim on,” she tells us. “My role is defen[s]e, the prosecutor prosecutes; we each tell a story and the jury decide[s] which story is the one they believe. They take the responsibility.”

Then, one night in her own apartment, Tessa is raped by a man she has been dating and already had sex with at least a couple of times, one of those encounters being a real quickie in the office of that guy, who happens to be a fellow barrister.

Tessa had been in court with cases like this before, and one of the real eye-rolling moments in “Prima Facie” (or, “on first impression”) is the fairly casual way in which this character reports on how much some Brits consume in a single night, mixing hard and soft liquor. The fact that both parties are confused in retelling their story on the witness stand is only part of the problem. With so much booze consumed, it’s a wonder they were ever able to perform the illegal act that put them in court in the first place.

Alcohol is only part of this victim’s dilemma. As Miller’s play lays out in both graphic and legal detail, Tessa’s confusion on the witness stand has nothing to do with how much vodka, gin, scotch, beer and/or wine she put into her body. (She is violently ill before the attack occurs.) Her confusion is the result of trauma, and unlike booze, the after effects of rape don’t dissipate over time.

Tessa tells us that one out of every three women will or has been the victim of sexual abuse. She asks us to look to our left and to our right to see those women. I didn’t have to look. Women all around me in the audience were sobbing audibly.

In other words, “Prima Facie” is the “Waiting for Lefty” of this century. It’s great agit-prop theater, and only time will tell if it has a longer shelf life than Clifford Odets’s play about taxi drivers on strike, first produced in 1935 to great acclaim. Miller falters only when she has Tessa go into a long dissertation into the bias against female defendants in these trials without ever mentioning the words “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

One can’t argue with Justin Martin’s direction of Comer, who recently won the Olivier Award for her performance. In addition to delivering a most logorrheic performance, Comer does it while pushing around two large tables and climbing up and down them to reconfigure Miriam Buether’s conference room set. Comer tackles the obstacle-course assignment with real gusto, although, again, you may find yourself stealing a breath for her.

Martin’s direction of Miller’s play is more questionable. He loads it up with a lot of effects that only distract from Comer. Immediately after the rape, Tessa endures a rain storm with real water falling on stage. Her first police interrogation is put on camera (video by Willie Williams), complete with a close-up of Comer’s face. Occasionally, when the actor impersonates another character, usually male, the amplification takes on an ominous echo (sound design by Ben and Max Ringham). And even in Tessa’s early scenes of ebullient success in the courtroom, a percussive score by Rebecca Lucy Taylor gives emphasis to a performance that needs no extraneous accents. Worst effect is Buether’s blue neon sculpture of Lady Justice with a red blindfold over her eyes. It hangs from the proscenium before the play begins, and would be kitschy looking for a musical version of “Perry Mason.” Here, it is downright gross.

When you have a star athlete performing at the top of her game, production values can sometimes get in the way.

Robert Hofler, TheWrap’s lead theater critic, has worked as an editor at Life, Us Weekly and Variety. His books include “The Man Who Invented Rock Hudson,” “Party Animals,” and “Sexplosion: From Andy Warhol to A Clockwork Orange, How a Generation of Pop Rebels Broke All the Taboos.” His latest book, “Money, Murder, and Dominick Dunne,” is now in paperback.