Sweden’s Isabella Eklöf has followed up her acclaimed debut “Holiday” with the Greenland-set “Kalak,” this time around opting for a male protagonist.

“He’s a guy, but the story is exactly the same,” she says.

“It’s still about sexual assault and ‘restaging’ your trauma, or looking for family and connection, but I have never explored that perspective before. An artist should be able to make art about anything, but it was strangely difficult. He does become more of a perpetrator. Why? I am not sure. Just because he has a dick, he becomes more dangerous.”

Eklöf, who previously co-wrote Ali Abbasi’s “Border,” based the story on an autobiographical novel by Kim Leine, with both of them writing alongside Sissel Dalsgaard Thomsen.

Produced by Maria Møller Kjeldgaard (Manna Film), “Kalak’s” production partners take in Mer Film (Norway), Momento Film and Film i Väst (Sweden), MADE (Finland), Dutch outfit Lemming Film and Polarama Greenland. Totem Films handles sales.

In the film, Jan (Emil Johnsen) is working as a nurse in Greenland. He wants to be accepted and become a “Kalak,” a true – or “dirty” – Greenlander. But he also needs to acknowledge a painful secret he has been hiding for years.

“Personally, I am not that drawn to fictional stories. There is enough weird stuff happening so that we don’t have to make things up, at least when it comes to art. Entertainment is a different story,” she adds.

“What drew me to Jan is his curiosity and joy, and his complete lack of borders. He is trying to understand Greenlandic culture, he wants to jump straight in. I just love it when people aren’t afraid.”

Despite having a family, Jan enters into sexual relationships with local women, at the same time awakening a memory he tried to keep dormant. He was sexually abused by his own father.

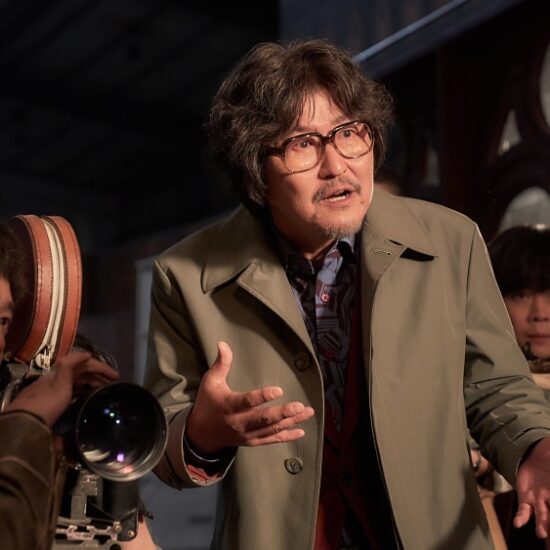

Isabella Eklöf

“When you don’t address these issues, it gets worse. That’s what happened in real life as well,” notes Eklöf.

“Those who have experienced sexual trauma often use sexuality as a tool of communication. It’s a way to get to know people, to get under their skin. He immediately falls in love with these women, he wants to be saved and to belong. If you have a broken connection with someone as close as your father, you are looking for someone to pull you out of that hole.”

But in “Kalak,” an intimate story becomes political.

“The metaphor is clear: He was raped the same way this culture raped all of Greenland. Until the 1970s, people were forcefully evicted from their villages and put in horrible concrete buildings, just because Danes assumed it would be better for them. They were infantilized, just like Jan’s father used to infantilize him.”

While his desire to blend in with the community he doesn’t belong to could raise eyebrows these days, for Eklöf, it’s a complex issue.

“The story is set around 2000, so today’s self-consciousness just isn’t present. But in Greenland, many people have Danish ancestry. Maybe he could have earned the right to call himself a ‘Kalak,’ but he is too enveloped in his own shit,” she says.

“I guess I wanted to defend that naivety a little bit. It’s potentially provocative for me to even be making a film in Greenland. But I did want to defend the fact that you can become a part of something – provided you do the work. But how and when? That’s a complicated question.”

Staying “humble” was crucial, she confesses.

“It had to feel real, even though I am not a Greenlander and never lived there outside of this context. Also, it’s not your usual story about ‘poor’ Greenlanders and their white savior. He is the most fucked up of all of them.”

And yet he still manages to surprise.

“I enjoy setting up dramatic situations where you expect something to happen and it never does. Like hanging up that [Chekhov’s] gun on the wall and never using it. In life, so often there is no resolution, especially when parents are involved. It’s part of my personal quest to have truth in filmmaking.”