In the mid-2000s, after about a decade of reporting in Japan, American journalist Jake Adelstein came upon a story that would change the trajectory of his life and career. Adelstein discovered that four major figures in yakuza organizations —Japan’s crime syndicates — had traveled to UCLA Medical Center to receive liver transplants. The most prominent was Tadamasa Goto, head of a notorious yakuza gang called Goto-gumi, who was able to gain entry into the U.S. only after pledging to provide information to the FBI about the yakuza and their cross-border financial operations.

The news was especially explosive as it appeared the four gangsters had jumped the transplant line thanks to large donations made to the medical center — and they ended up providing little significant information to the FBI.

For Adelstein, the story came with some obvious risks. Getting on the wrong side of major crime figures could very well lead to retaliation (the Goto-gumi was known for ignoring the rules that some yakuza clans make at least a pretense of following, such as avoiding unnecessary harm to “civilians”). But it ultimately paid off. The story helped cement Adelstein’s reputation as an unflinching chronicler of organized crime in Japan, propelling him to minor celebrity status as one of the primary experts on a shadowy underworld few had access to. This would be an impressive feat for any journalist in Japan, but in Adelstein’s case, it was downright extraordinary.

After leaving Missouri at age 19 to pursue his interest in Japan, Adelstein graduated from Tokyo’s Sophia University in 1993 and landed a coveted job as a cub reporter at the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of Japan’s leading news outlets and, at the time, the biggest newspaper in the world based on circulation. He was the first Westerner to be hired as a reporter at the paper.

“For a foreigner to learn Japanese that well, report and write articles in Japanese, work and function inside that culture, was truly impressive,” says Naoki Tsujii, who started with Adelstein at the Yomiuri’s Urawa bureau, north of Tokyo.

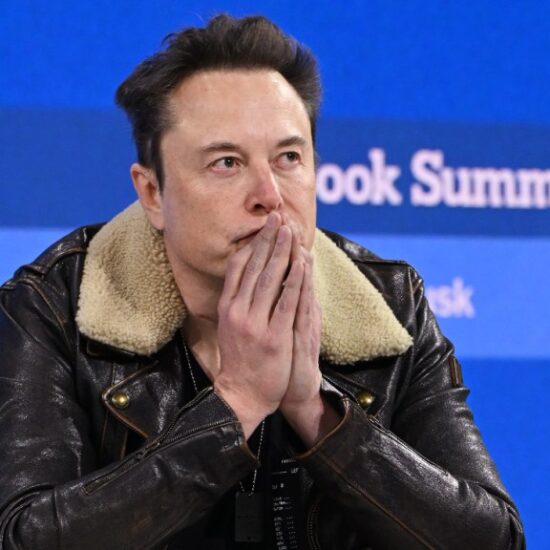

After leaving the Yomiuri in 2005, Adelstein would thrive as a freelance journalist, contributing articles to The Daily Beast, Vice and the Los Angeles Times, among others. He would also write several books, most notably the 2009 memoir Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan, which now has been adapted into a limited series from Endeavor Content and HBO Max, with Michael Mann — producer of Miami Vice and writer-director of the cinema crime classic Heat — serving as exec producer and directing the pilot. The show stars West Side Story’s Ansel Elgort as Adelstein, chronicling in painstaking, albeit typically stylish detail — this is Michael Mann, after all — how a wildly ambitious, hardworking young American was able to secure a job as a crime reporter and develop contacts within the cloistered world of the yakuza. It is, by any measure, an improbable tale of grit and determination. But with the high-profile nature of the show, which debuted April 7 on HBO Max, there is renewed focus on the veracity of some of the stories Adelstein has been telling about himself over the years — under the guise of nonfiction memoir. Did Adelstein, for instance, really use aikido skills to beat up a huge yakuza bouncer? Was he the target of yakuza “snipers”? Did female sources agree to give him information only if he would sleep with them — with one woman in his book throwing a wad of 10,000 yen ($100) bills at him and demanding sexual satisfaction? Among those who have known and worked with Adelstein, sources assess that some of his more far-fetched adventures run the gamut from merely colorful and larger-than-life to “exaggerated” or, simply, “fiction.”

In early April, I met up with Adelstein on a terrace at the Roppongi Hills complex where Tokyo Vice premiere events were taking place to discuss some of the doubts surrounding his version of a handful of the events in his memoir, and his subsequent journalism. (In the interest of transparency, I covered Adelstein’s news conference at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan for its in-house magazine in 2009 and quoted him in a THR article in 2013 about a proposed film version of Tokyo Vice that never came to fruition.) Adelstein is an engaging raconteur, but one whose narratives frequently shifted during our two hours of conversation.

On the fundamental question of his memoir’s most extravagant tales, Adelstein insists: “Nothing in the book is exaggerated. Everything is written as it happened.” (A disclaimer in the book says that Adelstein changed names and nationalities of sources, but not situations.)

Endeavor Content/HBO Max’s Tokyo Vice stars Ansel Elgort (center) as Jake Adelstein, the first Westerner to work at Japanese news outlet Yomiuri Shimbun.

Courtesy of HBO Max

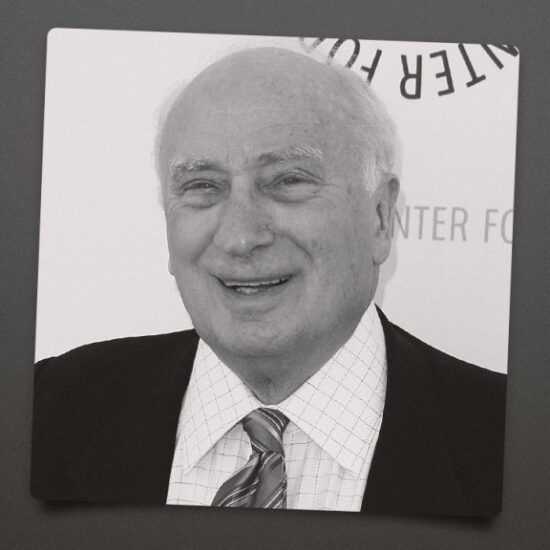

For Tokyo Vice’s Oscar-winning exec producer John Lesher (Birdman), the question of whether Adelstein is telling the truth is immaterial since, he’s quick to point out, the show is merely “inspired” by the book. “There were so many things that we embellished and created that had nothing to do with, let’s call it ‘the real Jake Adelstein story,’” says Lesher. “Whether the book is true or not, you should take it up with him and the people depicted in the book. I wasn’t there.”

Someone who was there at the beginning with Adelstein is his former colleague Tsujii. On the HBO show, a Francophile character inspired by Tsujii is referred to as Tin Tin, while in the book he’s called “Frenchie.” Tsujii laughs at the book’s description of him: “He was always immaculately coiffed, wore tailored suits and was constantly reading some obscure Japanese novel or French masterpiece.”

“Nobody has ever called me Frenchie, that’s a creation of his,” says Tsujii, now a literature professor at Kyoto University of the Arts with multiple novels to his name. “Newspaper journalists like us … all wore very plain suits and ties.”

Tsujii emphasizes his admiration and affection for Adelstein repeatedly during a lengthy video call and in two emails afterward.

“I believe it was dangerous for him to write about the Goto-gumi,” says Tsujii. “I think most Japanese journalists would have given up if they were threatened.”

But Tsujii has worked as a journalist, written novels and teaches creative writing, and he knows the difference between the disciplines.

“Japan is a country that works according to systems, so there are certainly things in the book that wouldn’t have happened the way they are written. There are definitely exaggerations,” he says using the English word. “But that’s part of what makes Jake interesting.”

Jake Adelstein, author of the memoir Tokyo Vice: An American Reporter on the Police Beat in Japan. Adelstein’s memoir is the basis for HBO Max’s limited series.

An early chapter of Adelstein’s memoir is titled “It’s the New Year, Let’s Fight,” which chronicles a spectacular martial arts duel between Adelstein and a co-worker at his first newspaper bureau year-end party. Adelstein, as the story goes, takes his opponent briefly off his feet with what he calls a “one-inch punch” from Wing Chun Kung Fu, and before long, two other colleagues are brawling. Tsujii was at the party and says, “I didn’t see any kind of fights.”

Adelstein maintains that such brawls were a regular occurrence. “Our bonenkais [year-end parties] were violent. The Yomiuri was like the military; there were a lot of people with a sports mentality. That’s what happened at the end-of-year parties at this company.”

In another episode in an action-packed first year, Adelstein goes undercover — with the blessing of two of his superiors — to impersonate the Iranian friend of a murder suspect.

“There is absolutely no way that a journalist at the Yomiuri would be allowed to go undercover — a journalist wouldn’t even ask their bosses if they could do that,” says Tsujii. “In Japan, even the police don’t do real undercover operations; it’s basically illegal and evidence can’t be gathered that way, though there have been some legal reforms recently. … The Yomiuri was very strict about that kind of thing.”

Adelstein insists the story is true. “We don’t have any rules like that … for obtaining information; it was by any means possible, except buying information is forbidden.” Though, later, in answer to another question about newspaper protocols, he says, “They take that shit seriously at the Yomiuri. … We had a notebook with our code of ethics and what we’re about — it’s like we’re fucking superheroes. It’s like the Green Lantern’s oath.”

To be fair, Adelstein is certainly not without his supporters, and there are those who back up his claims about his life being threatened after writing about Tadamasa Goto. “Goto was the scariest and most dangerous yakuza of his time,” says Grant Newsham, an acquaintance of Adelstein’s and a former U.S. Marine colonel and diplomat who spent years advising Morgan Stanley Japan on risk management, including how to avoid yakuza front companies. “I’m surprised Goto didn’t kill [Adelstein], and I think he would have if he could have gotten away with it.”

As depicted in the opening pages of Adelstein’s memoir, a Goto-gumi enforcer made what appeared to be a direct threat on Adelstein’s life at a face-to-face meeting, rather dramatically telling Adelstein not to report the story about Goto agreeing to provide information to the FBI: “Erase the story, or we’ll erase you. And maybe your family.” According to Adelstein, he was accompanied at this meeting by a police detective (the meeting is dramatized on the HBO show, with Ken Watanabe as the detective).

The offices of the Japanese news outlet Yomiuri Shimbun.

Kyodo/Newscom

When it’s put to Adelstein that it seems unlikely a gangster would threaten to kill him in front of a policeman, he offers up an alternate translation of the threat: “It was more like, ‘Either the article disappears or something else disappears. You have a family, right?’ in Japanese.”

A key element of the Adelstein story has been the five-plus years he spent under the protection of the Tokyo police beginning in March 2008 to keep him safe from Goto’s thugs. Many who saw Adelstein in Tokyo during that time noted he kept a high profile for a man in fear of his life from a genuinely dangerous gangster.

CBS’ 60 Minutes interviewed Adelstein at his then-Tokyo home about the threat to his life for an installment that aired in November 2009. Asked by Lara Logan what he did to stay alive, Adelstein replied, “You have to keep your rooms shuttered, because you don’t want a sniper to pick you off across from somebody’s house.” Yakuza weapons of choice are widely known to be knives, the odd samurai sword and pistols. There is no history of yakuza snipers. Put to Adelstein, he initially denies making the remark before noting he was playing it for laughs. “If I said it, I was joking because I was not fucking serious. … I don’t think anyone took that seriously. … I guess when I’m joking sometimes it doesn’t come across, sorry.”

Lara Logan interviewed Adelstein for a 2009 segment for 60 Minutes.

Courtesy of 60 Minutes

Adelstein’s own frequent use of colorful quotes attributed to unnamed sources in news articles has long raised eyebrows among foreign correspondents and others in Tokyo. The quotes come from yakuza, police, politicians, public officials and members of the public. THR asked him about a selection of 25 of his articles with such quotes published in the L.A. Times, Asia Times, the Daily Telegraph, Forbes, The Atlantic and The Asia-Pacific Journal.

At the end of our interview, Adelstein invited THR to come to his Tokyo home three days later to look at his reporter’s notebooks and other materials in order to verify the existence of his anonymous sources, with the understanding they wouldn’t be exposed. The following day, he emailed to say he needed more time to prepare and that THR would have to sign a non-disclosure agreement drawn up by a lawyer. Adelstein rescheduled the meeting for two weeks after the interview but canceled it less than an hour beforehand.

(Adelstein on April 20 sent a message to a senior executive at THR’s parent company: “In Japan … police and government officials cannot share confidential information with reporters without violating the civil servants laws … I can’t in good conscience share my sources.”)

Occasionally, improbable phrases seem to emerge from the mouths of more than one of Adelstein’s unnamed sources. In an article about the decline of the gangs in The Daily Beast in March 2014, Adelstein quotes a disgruntled yakuza complaining about paying the gang’s membership fees but not being able to use its name to intimidate people: “Can you imagine running a McDonald’s without being able to use the golden arches?” Variations of this quote appeared in articles by Adelstein in The Japan Times in October 2015 and in The Washington Post in April 2017, seeming to be attributed to two different gangsters.

Early questions about the legitimacy of Adelstein’s yakuza exploits and contacts emerged in 2010 when he was hired by National Geographic as a consultant and fixer for a documentary called Crime Lords of Tokyo. Philip Day, the director-producer on the project, says he was looking forward to meeting Adelstein and some of the many colorful characters that recur through Tokyo Vice’s pages.

But before Day and his crew arrived in Tokyo, they began to have doubts about Adelstein when he called to say he’d been beaten by a yakuza in the street with a phone book. “The way he described it, it didn’t sound credible at all to any of us,” recalls Day.

Tokyo Vice producer John Lesher.

Matt Winkelmeyer/Getty Images

Producer Calder Greenwood remembers his first impression on meeting Adelstein: “His outfit, his demeanor was sloppy and crude, with no charisma. The real Jake Adelstein was a far cry from the hero in the book.”

More material to their task, the Nat Geo production team soon became concerned that Adelstein didn’t have the yakuza connections he said he did.

According to Day, Adelstein’s strategy was to have the crew meet and interview a number of peripheral characters in order to finally gain access to an aging former yakuza. The ex-mobster, who has since died, was said to have worked for a time as a driver for Adelstein (who also says he doubled as a bodyguard) but was then long retired and not the kind of “crime world insider” the filmmakers felt they could base their production around.

As tensions were beginning to mount, Adelstein suddenly announced — in the middle of the three-week shoot — that he was traveling to the U.S. for his daughter’s birthday. In retrospect, Day says it was “the best thing that could have happened.” The team quickly shifted its reliance to another fixer.

With the assistance of the new fixer and a series of introductions, they were able to track down three active gangsters — two brothers and a senior figure in a Tokyo crime family — as well as a yakuza turned Buddhist priest and a woman once kidnapped by the mob.

On his return to Tokyo from the States, instead of being pleased at the progress, Adelstein was furious, says Day. “Next thing, we heard via National Geographic that Adelstein had contacted Fox [then owners of Nat Geo] and told them that the brothers we had interviewed had called him in the dead of the night and threatened to kill him,” recounts Day. “I didn’t believe it for one second — not one second — and I told him that he was full of it, which didn’t go down well.”

Day points to this exchange as the trigger for what came next: Adelstein filed a lawsuit in the District of Columbia against National Geographic Television.

The suit alleged that Adelstein’s life would be in danger, along with that of anyone involved in the film, if it was broadcast and that the yakuza interviewed for the doc had withdrawn their consent to appear. To back this up, Adelstein included in the complaint anonymous quotes from yakuza and police sources. As part of the suit, Adelstein said he agreed to work on the show but had an understanding with producers that members of the yakuza or anybody with current dealings with the yakuza couldn’t be interviewed. The show aired in 2014.

The following month, the case was settled and dismissed “with prejudice” — meaning Adelstein would be unable to try to sue again.

“Jake Adelstein might have known that one driver, but in my opinion, he didn’t have any access to any other yakuza,” says Day. “I don’t think half of that stuff in the book happened, it’s just in his imagination. It’s fiction.”

This story first appeared in the April 27 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.