When critics compare films in the same genre to each other, it’s not always a good thing.

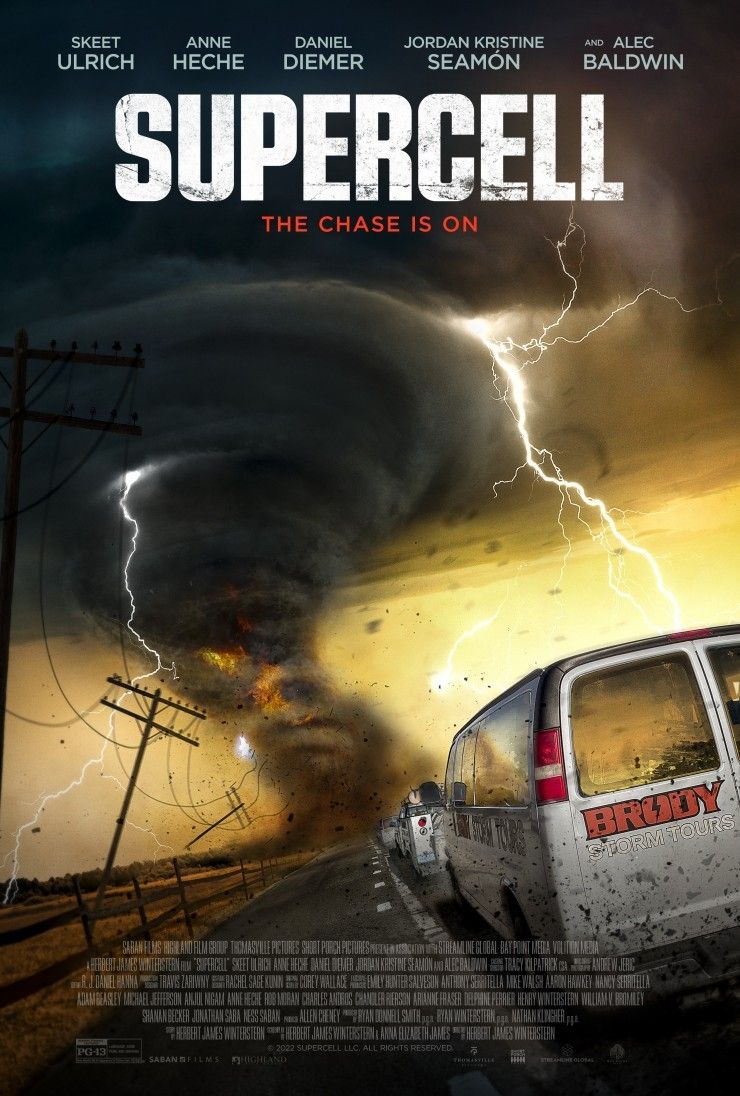

In the case of Saban Films’ Supercell being compared to the 1996 hit, Twister, that is one comparison director Herbert James Winterstern gladly welcomes. The budget for Supercell was significantly smaller than that of Twister, so the imagery that Winterstern was able to pull off was quite impressive.

Supercell follows William Brody (Daniel Diemer), the son of a legendary storm-chaser who was killed by one, trying to save his family’s business that now belongs to the reckless Zane Rogers (Alec Baldwin), who sees storms as tourist attractions rather than the deadly forces of nature that they are. When his destiny arrives in the form of one of the most powerful storms on record, William leaves his mom (Anne Heche) and home behind to team up with his father’s ex-partner, Roy Cameron (Skeet Ulrich), barely surviving a tornado yet determined to chase one of nature’s most terrifying creations: “the bear’s cage.”

There is also no shortage of star power in Supercell, Alec Baldwin, Skeet Ulrich, the late Anne Heche, and Daniel Diemer all appear in the storm-chasing thriller. What makes this film stand out in this oversaturated genre is the orchestral score by composer Corey Wallace.

Wallace spent years collaborating with the director before the script was even finished, finalizing the main theme two years before cameras started rolling. The end result is thematic music that is introduced pensively in a solo flute and grows throughout the film into a grand adventure during a climactic action scene.

Wallace spoke with No Film School about composing the score for SupercellI, and his advice for composers looking to make scores highlights the beauty and intensity of a film.

No Film School: How would you describe your score to Supercell?

Corey Wallace: For Supercell, we aimed for a return to classic, orchestral film scores that have memorable, hummable themes. Director Jamie Winterstern and I grew up on the movies of the ’80s and ’90s, so we really wanted to return to that aesthetic. The goal is to sweep audiences away with emotions of wonder, love, death, and adventure, and leave audiences humming a tune as they leave the theater. We drew stylistic inspiration from greats like John Williams, Alan Silvestri, and James Horner (and we’re not shy about it), but we worked extensively to make sure the themes are unique and specific to our story.

NFS: As a composer, how do you get across your musical ideas to filmmakers who, more often than not, don’t have musical backgrounds?

Wallace: We make “mockups” using what’s called “instrument samples” to simulate the sound and feel of a real orchestra. To put it in comparable terms, mockups are like pre-visualizations (previz). They have all the same movements and shapes of the real thing, but they don’t feel real, lacking definition, depth, humanity, and emotion. Before my time, composers would play their ideas for directors at the piano and describe how the full orchestra would sound (similar to a storyboard or animatic). The director would not truly know the sound of the score until hearing it on the scoring stage. But now, mockups give a director and composer much more control over the scoring process. Orchestra samples are becoming increasingly sophisticated, so they can come pretty close to mimicking the real thing. That said, the real movie magic doesn’t happen until hitting record on a live orchestra.

NFS: You worked with director Herbert James Winterstern on the NBC series Siberia ten years ago. Did he reach out to you because of Siberia, or was it just a coincidence that you would work together again?

Wallace: It’s not a coincidence. Jamie and I have been friends and collaborators for the past 15 years since we met at USC. In between Siberia and Supercell, he co-launched the production company SwipeMarket which also does video marketing, so we continued to work together in that space. When Jamie developed his idea for Supercell, he reached out to me right away because he knew how important music was going to be for him and the movie. We started working on musical themes in between other projects before there was even a finished script. Two years before cameras started rolling, we had finalized our “Main Theme” which was a huge advantage when we started to score the picture.

NFS: How do you think you have changed as a composer in the last ten years? If at all.

Wallace: With experience I’ve become much more well-rounded stylistically, as I’ve had opportunities to work in so many different types of media and genres. The scoring style of Supercell has not been the industry norm over the last 10 years. Even though I had always imagined writing scores with big orchestras and melodies (the reason I got into film scoring in the first place), I’ve had to learn many other modern techniques and styles. These days, I’m also doing music with electronics, sampling, and audio manipulation that I never dreamed of 10 years ago.

NFS: Supercell is your first natural disaster film. Was the scoring process different from other films you have worked on?

Wallace: Yes, but not because it’s a weather-film. Most scoring jobs are unique in their own right depending on the story, the schedule, the budget, and most importantly, the director. Working with Jamie is a unique experience, and our process is not quite like any other I’ve had in my career. He’s very hands-on and specific, but at the same time not controlling.

A unique part of the Supercell score is how much we worked on it in pre-production. I’m used to starting a score around the time a fine edit is completed, and my brain has been wired to come up with ideas in response to a picture (how it looks, feels, how it makes me feel). Working on musical themes based on general ideas and concepts was a different experience, but ultimately valuable.

NFS: Sound design plays a big part in natural disaster films. How closely did you interact with the sound designer on the film?

Wallace: First, I’d like to give a big hand to Nathan Ruyle and his team at This is Sound Design Studios. They absolutely did their part in bringing this story to life. We didn’t have too much interaction because I started working on the film so much earlier than the sound team. When they started, I had already scored about 90% of the film. That said, we did spot the film all together early on, so we had a sense of where sound would take over and where music would shine. There are several important scenes without music because we knew it would be more important to hear all the details of the sound. Score often plays sub-text, but there’s nothing sub-textural about being trapped in a van and being pounded by gorilla-hail. That’s extremely visceral, and it’s the sound that immerses the viewer in that experience.

NFS: When creating the Supercell score, did you face any challenges?

Wallace: One of the downsides to working on a score before picture is that the film that gets shot might not quite be the film the director had imagined. Beforehand, we discussed a lighter, more adventurous score, but Jamie thought the film turned out lighter than expected, so he wanted the score to highlight the darker, brooding aspects of the characters and story. It took some time to get my head wrapped around the new score concept.

The same went for themes. In pre-production, we had three themes solidified, but only one, the Main Theme, made it into the final score. The first theme Jamie fell in love with was written for the character Zane, but the tone was based on him being more of an antagonist. Perhaps it’s how Alec Baldwin played the part or how the edit turned out, but he was a different character than I had thought when reading the script.

NFS: Can you talk about the equipment or programs that you use frequently that you would recommend?

Wallace: For my DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), I use Logic, Cubase, and Pro Tools depending on the nature of the scoring work. For Supercell and other primarily orchestral projects, I love working in Cubase. The orchestral samples I used in the mockups and to sweeten the final mixes are largely from Spitfire Audio. Halfway through scoring the film, Spitfire released a line of samples recorded at Abbey Road in London, which is something I have been eagerly awaiting for a long time. There is a magic to the sound of that recording space. I also love Spitfire’s Appassionata Strings, which are my new favorites for lush, soaring melodies. Those samples really elevated the sound of the score in places we didn’t have the budget to record with a live orchestra.

NFS: What would you say makes a good film composer?

Wallace: A good film composer is a good storyteller at the core. Everybody involved in the making of a film is trying to serve the story in the best way possible, we’re all just using our own sets of tools. Putting ego aside, being a team player, and putting the needs of others first is paramount.

I’d also say it’s a plus to have a healthy balance of confidence and ignorance. Confidence helps you sell yourself to get the job and can be a great ally when staring at a blank page (or computer monitor). Even though that’s terrifying, knowing you’ve done it before and can do it again is helpful. To finish something under a deadline, you have to have confidence in your abilities and ideas, and also be a bit ignorant of your own shortcomings so that you don’t second-guess yourself to death. Ten years ago, if I knew then just how much I didn’t know, I would never have been able to function, but I worked within my abilities and grew from there.

Ignorance also opens the door to possibilities. Not thinking that there’s one exact solution can lead to new ideas and innovation. Making something truly original requires a lot of trial and error experimentation, and a willingness to ask yourself “what if?” and see what happens. By not knowing exactly where you’re going, you can wind up in a place you never expected.

NFS: In your early days as a composer, you assisted Christopher Young. What was one of the lessons you learned from him?

Wallace: After being Chris’ student at USC and his assistant for part of 6 years, the list of lessons is quite long. Chris gave me the “starter kit” of tools to help me get going in this industry until I became experienced enough to have my own.

Everything from how to talk to directors during a spotting session to developing score concepts to compositional techniques for many scoring situations. It was a huge advantage to be able to tell a director that I knew exactly how to score a certain type of scene (even if I’d never done it before) because Chris had given me a set of techniques that I could start from.

The best lesson, though, was the importance of film score melodies, how to use them, and what makes them work well. Chris is a huge proponent of melody in film scores, and as his assistant, I spent hours analyzing and writing about melodies.

Even though I learned a lot on a technical level, he also taught me that composing needs to come from your heart, not your head. There’s a time and a place for using analytical tools to craft, refine, and polish, but that initial creative moment needs to come from a different place inside.