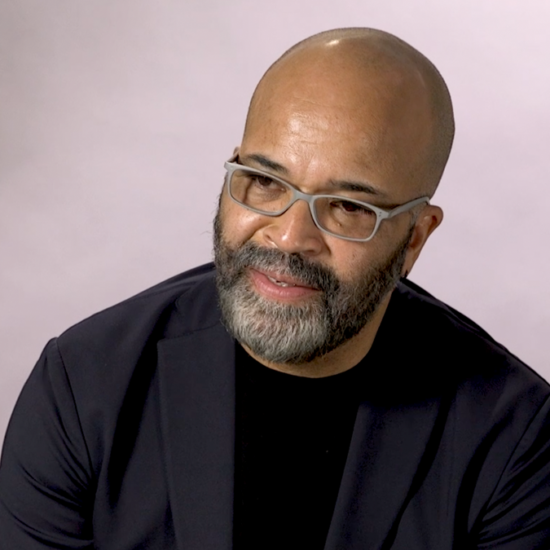

Fashion historian Raissa Bretaña details how Little Richard cultivated his unique style, from his hair, makeup and clothing, and the many musicians he inspired along the way.

Music legend Little Richard is as remembered for his unapologetic flamboyance as he is for his dynamic vocals and electrifying stage presence. As the self-proclaimed originator of rock ‘n’ roll, he laid the foundation for a genre that would define music for the second half of the 20th century. From the very beginning of his storied career, he cultivated a distinctive sense of style to go with his sound, and became known for ostentatious performance attire before such histrionics were a prerequisite for rockstar fame. Just as musicians immediately rushed to record covers of his hit songs, so too did they imitate his manner of dress. Little Richard’s sartorial influence remains far-reaching, and many artists have borrowed elements of his signature look over the years—but what inspired it? His was a wardrobe that left an indelible legacy, drawn from the aesthetics of his musical predecessors and queer contemporaries, and later, countercultural trends.

Richard Penniman began his career at a pivotal moment in music history when record labels sought to broaden the market for Black artists by appealing to white audiences. When he released “Tutti Frutti” in 1955, it became an instant hit and ushered in a new era of popular music. Pat Boone and Elvis Presley both recorded covers of the song the following year, which outperformed the original. Undaunted, Richard quickly followed with another uptempo hit, “Long Tall Sally.” He performed both songs in the musical film “Don’t Knock the Rock” (1956). Supported by a band of Black musicians, they played to an enthusiastic audience of white teenagers—a testament to Richard’s burgeoning success as a “crossover” artist. Historically, instances in which Black musicians were permitted into white spaces called for a display of respectability in the form of inoffensive attire. Pioneering rhythm and blues singer Fats Domino, another musician who broke the race barrier, opted to perform in innocuous dinner suits. In “Don’t Knock the Rock,” Little Richard also sports a tailored ensemble—but with a subtle rebellious twist. The slightly oversized jacket and baggy trousers accommodate Richard’s frenzy of kinetic energy, and his leg thrown up over the piano he is playing reveals a tapered fit around the ankle. This cut recalls the proportions of the zoot suit, which emerged as a popular style among African American performers in Harlem during the 1930s and was made iconic by jazz bandleader Cab Calloway in the film “Stormy Weather” (1943). The garment was prevalent among young men from ethnic minorities during World War II, and became the center of racial conflict during the Zoot Suit Riots in Los Angeles. Little Richard’s suits during this period were not quite as exaggerated as those infamous zoot suits—with their broad-shouldered, peg-legged silhouette—but appeared conspicuous against the backdrop of the straight-laced 1950s.

During the 1950s, gender roles—and gendered clothing—were strictly defined, and any deviation from the norm was seen as subversive. Little Richard’s early career wardrobe was not inherently flamboyant; still, he was able to craft a ritzier image through personal grooming. He began experimenting with cosmetics at an early age and had a stint as a drag performer before he made it in the music industry. However, the makeup Richard wore as a rock ‘n’ roll sensation was not about female impersonation—but rather, about enhancing his natural features. Gifted with impeccable cheekbones and perfectly arched eyebrows, he was encouraged to start wearing pancake makeup by the openly gay singer Billy Wright. Known as the “Prince of the Blues,” Wright was one of Little Richard’s greatest influences during his formative years—not only through his colorful musical stylings, but also through his personal appearance. Wright sported a lofty pompadour hairstyle and pencil-thin mustache, which Richard would adopt and make his trademark.

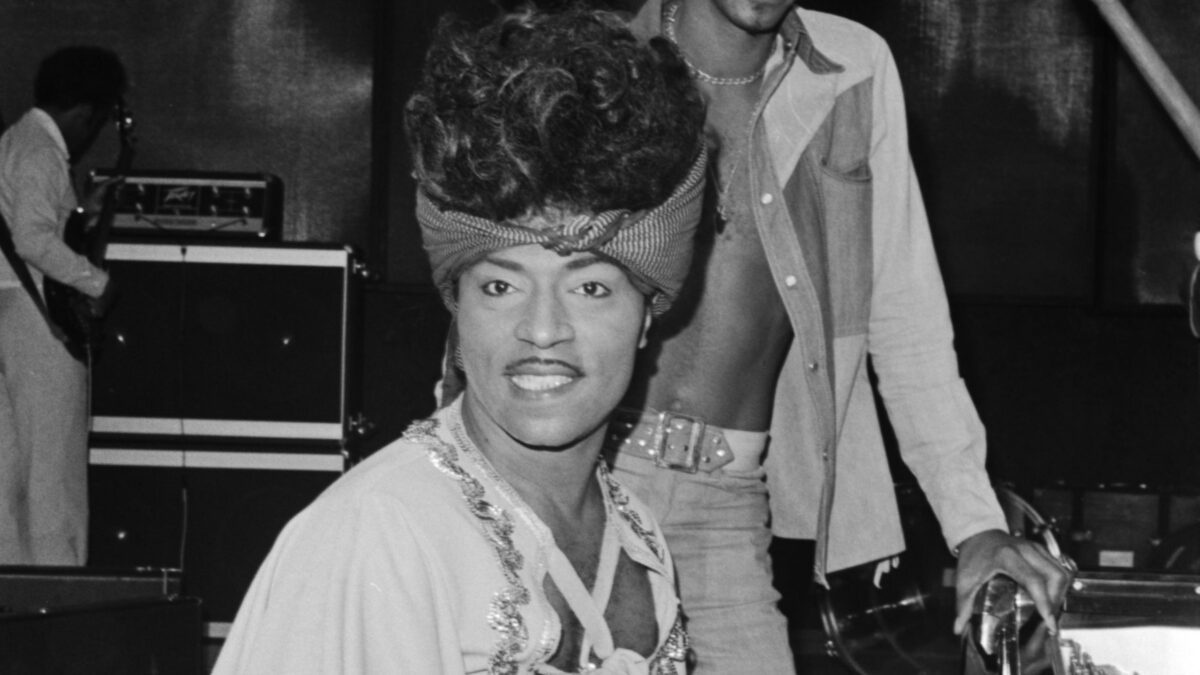

Another African American rock ‘n’ roll innovator who shared these traits was Esquerita, whom Richard met at a bus station in his native Macon, Georgia. He was also openly gay, and habitually wore bejeweled sunglasses that added a touch of panache to an image that served as inspiration for Little Richard’s look. Both men achieved stratospheric height by processing, straightening, and sculpting their textured hair. Richard’s signature pompadour would become more and more exaggerated as his career continued. What began as a six-inch quiff in the 1950s would be teased into a bouffant in the 60s, before being supplanted by wigs that towered up to a foot by the 70s. Although he styled himself after two queer artists of his time, Little Richard had a troubled relationship with his sexuality, due in large part to his religious upbringing. In 1957, at the height of fame, he abandoned the hedonism of rock ‘n’ roll to pursue a course in Bible study.

After a few years focused on gospel music, Little Richard returned to the genre he helped create with his 1964 album, “Little Richard is Back (and There’s a Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On).” Having toured the United Kingdom with The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, he witnessed the shifting tides of men’s fashion beginning to take hold. Little Richard’s wardrobe became gradually more exuberant throughout the decade—coinciding with the emergence of the Peacock Revolution, which challenged traditional notions of gendered dressing and injected menswear with effeminacy not seen since the 18th century. It was an aesthetic moment that grew out of London subcultures, with Carnaby Street and Kings Road serving as epicenters of boldly patterned polyester shirts and slim-cut suits in vibrant hues. The Peacock Revolution broadened the definition of masculinity, while encouraging individual expression and nonconformity—qualities that would come to define Little Richard’s style persona.

Following the release of his 1970 album “The Rill Thing,” Little Richard embraced an even greater sense of fabulosity. He essentially took countercultural street style, elevated it to a theatrical degree to match his showmanship, and brought it into the mainstream through his music. He dreamed up resplendent stage costumes for his concerts and television appearances, and had them fabricated by Detroit-based designer Melvin James. They ranged from gender-bending jumpsuits to blouson blouses, from crop tops to capes. Each look was fit for a peacocking performer, and festooned with no shortage of sequins, rhinestones and mirrored squares. As an aesthetic, it was unapologetically camp—one that provided a blueprint for artists in the emerging glam rock genre like David Bowie and Elton John, who have both cited Little Richard as a major influence.

Interestingly, Richard’s getups only grew more bombastic as those who were inspired by him began to outearn him, which was perhaps a visual manifestation of his lifelong fight to be given his due. That his signature style has been reinterpreted by musicians for decades is a testament to his sartorial legacy. Little Richard pushed the boundaries of gender, race and sexuality through his music and his clothing—a true originator of rock ‘n’ roll.