A festering dispute over how writers are compensated in the streaming era came to a head Monday night, as leaders of the Writers Guild of America called on their members to stage Hollywood’s first strike in 15 years.

The boards of directors for the East and West Coast divisions of the WGA voted unanimously to call a strike effective 12:01 a.m. Tuesday, the union said in a statement.

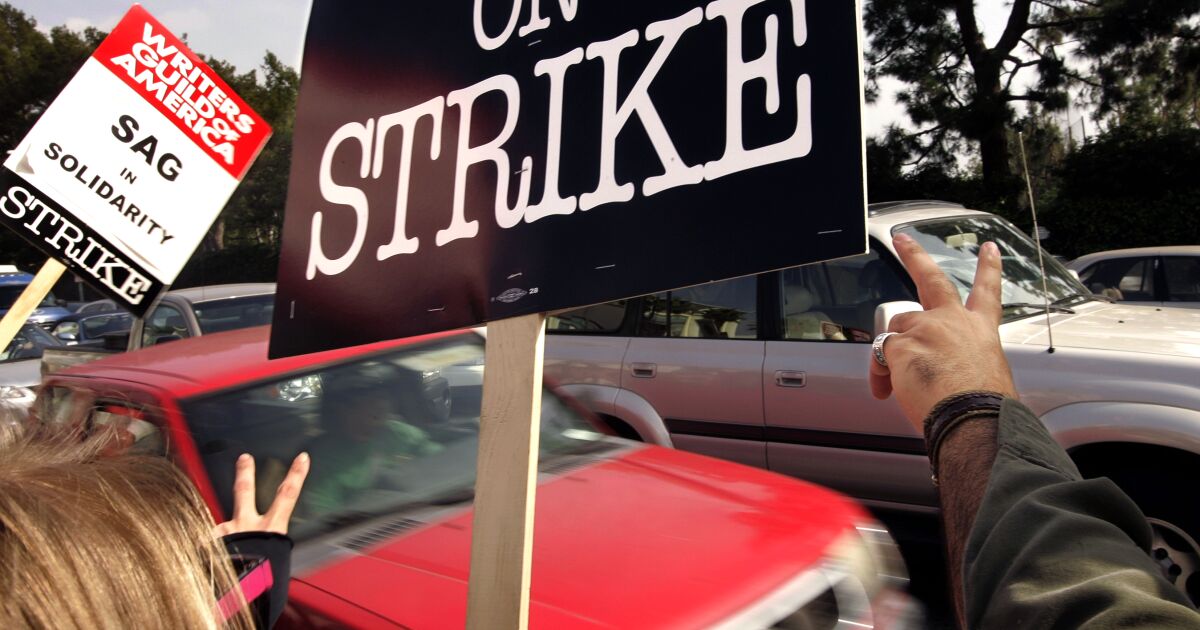

Thousands of WGA members were set to walk picket lines across Los Angeles, New York and other cities Tuesday after the union was unable to reach a last-minute accord with the major studios on a new three-year contract to replace one that expired Monday night.

“The companies’ behavior has created a gig economy inside a union workforce, and their immovable stance in this negotiation has betrayed a commitment to further devaluing the profession of writing,” the WGA said in a statement. “No such deal could ever be contemplated by this membership.”

In a statement, the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers said it offered “generous increases in compensation for writers as well as improvements in streaming residuals.”

The alliance, which bargains on behalf of the major studios, said it was prepared to improve the offer but was “unwilling to do so because of the magnitude of other proposals still on the table that the Guild continues to insist upon.” The alliance said primary sticking points included the guild’s demands over mandatory staffing levels and duration of employment.

Writers are seeking a larger slice of the streaming pie that has dramatically transformed the television business. They voted by a historic margin in favor — 98% to 2% — to grant a strike authorization sought by their leaders if they couldn’t reach a deal on a new film and TV contract on behalf of 11,500 members.

The walkout, which could last for weeks or months, is expected to halt much of TV and film production nationwide and reverberate across Southern California, where prop houses, caterers, florists and others heavily depend on the entertainment economy. The previous writers strike in 2007 roiled the industry and lasted 100 days.

The walkout will also mean temporary job losses for crew members and comes at a difficult time for the Los Angeles region, where many businesses are still attempting to recover from the effects of the pandemic and major employers are slashing payrolls. Hollywood studios have laid off thousands of workers as Wall Street investors punished them for losses linked to their streaming businesses.

Even before negotiations between the WGA and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers began March 20, many in Hollywood believed a strike was inevitable because the sides remained so far apart on key issues.

WGA leaders warned that their members faced an “existential” threat to their ability to earn a living in Hollywood.

Although streaming has been a boon for television, it has upended how writers are compensated. Writers say that they work longer hours for less pay and that they no longer can rely on a steady stream of residual income they used to get in the days of broadcast TV, when successful shows lived on for years in syndicated reruns or the once-lucrative home video market.

The median weekly pay for writer-producers declined 23% over the last decade when adjusting for inflation, according to a WGA survey. When accounting for inflation, screenwriter pay declined 14% in the last five years, the report said.

The union has demanded compensation and other improvements , including increases in minimum pay, residuals for streaming and higher contributions to the WGA health and pension plan. The union said its proposals would have gained the writers $429 million a year.

Additionally, the WGA wants to crack down on practices it says have eroded writers’ pay, such as the prevalence of so-called mini-rooms, where small groups of writers on short-order series are hired to craft the arc of a show before it is commissioned, replacing the traditional practice of producing pilot episodes.

“We made it crystal clear to them that we needed a sea change,” WGA West President Meredith Stiehm in an interview. “And it fell on deaf ears; they acted like they didn’t understand or they didn’t care.”

David Goodman, co-chair of the negotiating committee, said that the breakdown became apparent in recent days.

“It was really very clear that the companies were unwilling to move on many of the very important issues we raised,” Goodman said, citing priorities such as writer compensation, proposals for feature writers and comedy writers and regulating artificial intelligence. “They kept wanting us to give up things that we just wanted to talk about and so as a result, we realized that they didn’t want to make a deal.”

For their part, the major studios have said their goal is to reach a fair deal. They’ve cited their own set of challenges, including pressure from investors to cut costs and build profitable streaming businesses, a slowing national economy and long-term declines in box office revenues. Amid the upheaval, companies such as Netflix, Warner Bros. Discovery and Disney have laid off thousands of employees.

“The AMPTP member companies remain united in their desire to reach a deal that is mutually beneficial to writers and the health and longevity of the industry, and to avoid hardship to the thousands of employees who depend upon the industry for their livelihoods,” the alliance said in a statement.

It’s uncertain how long such a walkout would last, particularly if there is no unifying leader to corral both sides as there has been in previous strikes. In 2008, it was Walt Disney Co. Chief Executive Bob Iger and then News Corp. President Peter Chernin who united both sides.

The shifting nature of the AMPTP has also complicated the picture because of the varied interest of its members. Now technology companies such as Amazon and Apple, whose core business is not entertainment, have a seat at the table alongside Hollywood-focused companies such as Walt Disney Co., Paramount Global and Warner Bros. Discovery. Netflix, which was just a mail order DVD business during the last strike, also is a key member of the bargaining alliance.

Studio executives have said they didn’t want a strike but prepared for the outcome.

“A strike will be a challenge for the whole industry, everybody involved,” Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav told attendees at a presentation for its streaming service, Max. “We’re assuming the worst from a business perspective. We’ve got ourselves ready. We’ve had a lot of content that’s been produced.”

Warner Bros. Discovery and studios have been taking various contingency measures for months in case of a strike, including accelerating deadlines for scripts and film shoots.

The effect of a strike on the major studios will vary. Some have a deep library of shows and films on hand that they can offer to keep viewers watching.

Netflix may have an advantage over other studios because it has a big international production presence. Many of its most popular shows and films are made in countries including South Korea and Thailand.

In an April earnings presentation, Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos said the company wants to avoid a strike but that if there is one, the streamer has enough content that it can “probably serve our members better than most” entertainment companies, he said.

“An extended strike that lasts three-plus months should meaningfully advantage Netflix,” Rich Greenfield, a co-founder of LightShed Partners, a technology and media research firm in New York, said in an April research note.

The reduction in costs from not having to produce shows could actually benefit studios, some analysts suggest.

For example, studios could use the work stoppage to terminate costly contracts with writers through so-called “force majeure” clauses that allow a studio to terminate the deal if there is a labor action that lasts for a set period of time.

“While we would not expect Warner Bros. to terminate its deals with star writers such as Chuck Lorre or Universal with Dick Wolf, there are lesser known writers who struck overall deals with studios that do not make economic sense today,” Greenfield wrote.

Although the WGA strike has drawn widespread support from other Hollywood unions, a protracted walkout will cause hardships for a wide swath of workers. During the last strike, many of those who lost their jobs — such as set decorators, lighting technicians and makeup artists — did not get their work back as studios scaled back production. The 2007 strike resulted in $772 million in lost wages for writers and production workers, according to the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corp.

The WGA has a strike fund to provide grants or loans to help its members make ends meet during a stoppage. The WGA had $19.8 million of assets in its strike fund as of March 31, 2022, according to its latest annual report.

Times staff writer Meg James contributed to this report.

Newsletter

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.