In a 2002 interview with Roger Ebert, the great Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki was asked about the moments of stillness that punctuated his films: the contemplative pauses that allowed his characters — and the audience — to catch their collective breath in between the plot points. “We have a word for that in Japanese,” Miyazaki explained amicably. “It’s called ma. Emptiness. It’s there intentionally.”

“Empty” is probably the last word one would use to describe the films Miyazaki has written, produced and directed under the banner of his Tokyo-based company studio Ghibli for the past 40 years.

Taken on a frame by frame basis, the filmmaker’s proudly hand-drawn output rivals anything in contemporary world cinema for intricacy, detail and imagination. Miyazaki’s worlds overflow with verdant landscapes and fabulous objects and creatures: moving castles, luminous sea goddesses, anthropomorphic public transit.

But there is nevertheless something spacious about their style that underlines the concept of ma while gently rebuking the freneticism of most North American family films — even those made by Pixar, whose brain trust holds Miyazaki in godlike reverence.

Even for Gen-X parents who came of age with Nintendo, sitting through a noisy, pandering exercise in brand extension like “The Super Mario Bros. Movie” can feel like a tour of duty; the most truthful moment in that film comes when a minor character cheerfully yearns for death as release from shimmering video-game purgatory.

At best, “Mario” is a victory lap around a sprawling stretch of intellectual property. While Ghibli’s films have often performed like blockbusters, they’re artworks, not product, reaching beyond formula toward something ineffable.

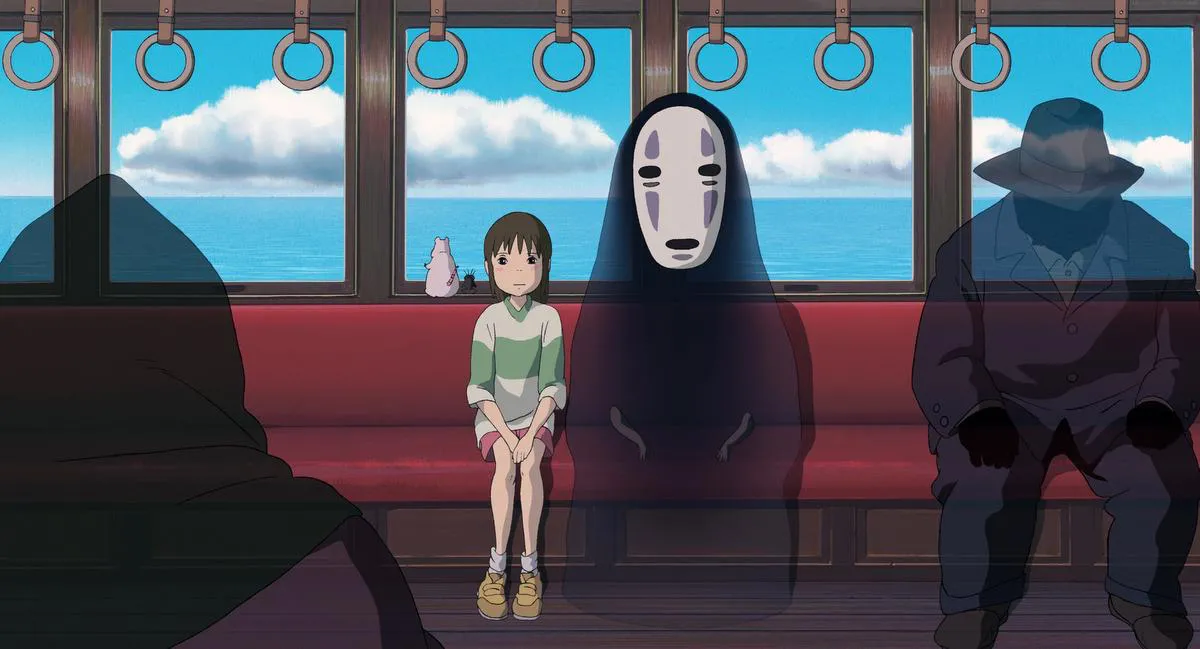

If Miyazaki’s work has a signature image it may be that of 10-year-old Chihiro, the intrepid heroine of 2002’s sublime coming-of-age fable “Spirited Away,” seated silently next to a hooded, benign spirit on a seaside ghost train headed into some other, ephemeral realm. It’s an instantly indelible tableau conjoining weightless enchantment with a precise and everyday sense of boredom: it’s somehow familiar and mysterious, like the memory of a dream.

“Spirited Away” is one of several Miyazaki masterpieces screening this spring as part of TIFF Bell Lightbox’s POP Japan series, which also includes spotlights on the jazzy, surrealistic crime films of the director’s countryman Seijun Suzuki and a survey of several seminal anime titles aimed primarily at adolescent audiences.

Both “Spirited Away” and 1988’s “My Neighbor Totoro” arrive at TIFF festooned with unlikely laurels, having recently cracked the British Film Institute’s decennial poll of the top 100 movies of all time — the only animated titles on the list, and each in their way sterling examples of Miyazaki’s ability to filter elements of native culture through larger, global fairy-tale archetypes.

Like “Spirited Away,” “Totoro” unfolds subliminally as a riff on “Alice in Wonderland” in which a lonely child is granted access to a magical realm somewhere between absurdism and allegory. The poetry of the work lies in the plain, matter-of-factness of the magic, which eschews convolution for Carroll-like simplicity. “There,” huffs a kindly, wizened witch in “Spirited Away,” after suddenly turning another character into a mouse. “Your body matches your brain.”

In 2013 — the same year he released the majestic period epic “The Wind Rises,” a sweetly fictionalized biopic about aeronautical engineer Jiro Horikoshi — Miyazaki invited a documentary crew inside the walls of Studio Ghibli to document his process: a dream for fans and contemporaries alike. The documentary’s title, “The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness,” is worthy of Shakespeare; the portrait that emerges is of a benign, emperor-like figure whose dedication to his craft is both exhaustive and exhausting.

Miyazaki was 72 at the time of filming and carries himself with a good-natured world-weariness that occasionally slides into existential despair. ““I’m a man of the 20th century,” he says at one point. “I don’t want to deal with the 21st.”

On a practical level, Miyazaki’s joke signifies a septuagenarian technophobe’s refusal of computer-generated tools and techniques. But it also hints at the deep-seated connection to the textures — and values — of the past that account for Miyazaki’s supremely controlling sensibility, which privileges perfectionism over efficiency. Like no less than Walt Disney, Miyazaki seeks to recreate the world in his image, but he’s less interested in dominance; not only are his movies more subtle and elusive than the bulk of Disney’s animated output, he’s made few enough of them to dodge charges of formula.

The relationship between the two animation giants has always been fraught; in his 1996 book “Starting Point,” Miyazaki wrote that Disney’s movies “showed contempt for the audience,” while in 1997, Miyazaki’s producer Toshio Suzuki reportedly sent a samurai sword to Harvey Weinstein — who was overseeing the U.S. release of the epic fantasy “Princess Mononoke” as part of an international distribution deal with Disney — accompanied by a note reading, simply, no cuts: Harvey Scissorhands, as the producer was known, was not amused.

“I defeated him,” Miyazaki said of Weinstein in 2010, a victory that signifies an even more heroic dimension 13 years later.

Later this summer, Miyazaki will release his first directorial effort since “The Wind Rises,” entitled “How Do You Live?” and inspired by (though not based on) a 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino. In 2018, Suzuki told media that Miyazaki was working on the film as a present for his grandson: “‘it’s (Miyazaki’s) way of saying Grandpa is moving on to the next world, but he’s leaving behind this film.’”

In “Spirited Away,” Chihiro gazes straight at us as she’s being ferried away from her world and into the unknown: we become a mirror for her stillness and her curiosity. Like the greatest artists, Miyazaki doesn’t just show us beautiful things: he teaches us how to look and also how to see.

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

does not endorse these opinions.

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/movies/2023/05/11/hayao-miyazaki-values-perfectionism-over-efficiency-art-over-product-it-makes-him-a-visionary-and-a-lonely-hero/spirited_away_miyazaki_tiff.jpg)

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/movies/2023/05/11/hayao-miyazaki-values-perfectionism-over-efficiency-art-over-product-it-makes-him-a-visionary-and-a-lonely-hero/the_wind_rises_miyazaki_tiff.jpg)