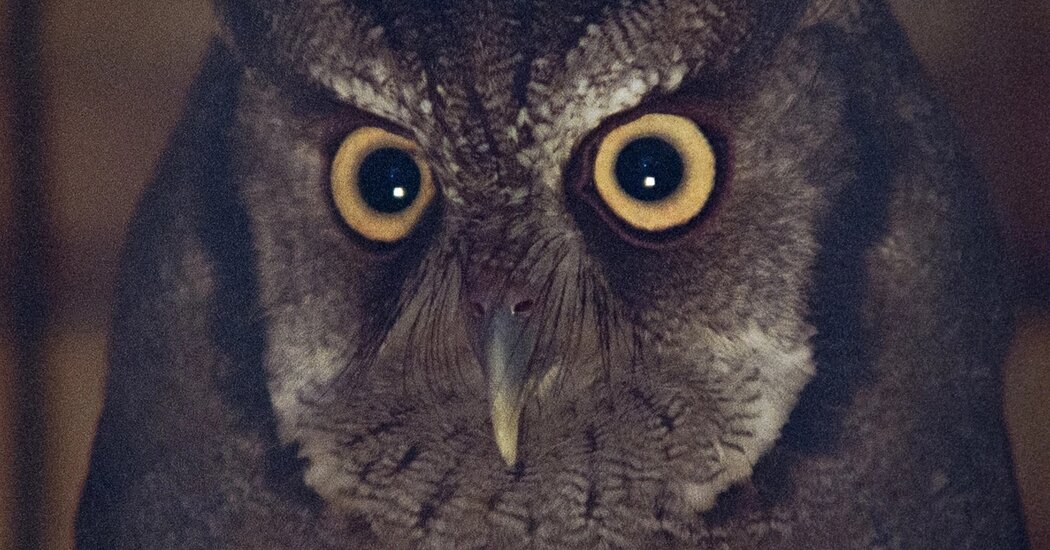

‘It Is Night in America’

Ana Vaz’s debut feature is a work of nocturnal ethnography — a documentary that invites us into a thicket of sound and darkling images so we may emerge with a fresh understanding of the world around us. “It Is Night in America” captures Brasília, Vaz’s hometown in Brazil, through two layers of obfuscation. The film is shot on grainy, expired 16-millimeter film stock, and with a blue tint that turns even daytime scenes into something out of a twilight zone. The camera’s subjects are the wildlife of the city — owls, capybaras, snakes, foxes and more — seen in the Brasília zoo and on the streets; the soundtrack is a viscous fog of ambient noise — crickets, wind, vehicle horns — interspersed with recordings of phone calls to forest officers to report sightings of animals. These dreamlike visions all accumulate into a parable about aggressive urbanization in the name of progress. What happens when our faunal kin are made invaders in their own homes? Vaz suggests that we learn to look not just ahead but also sideways, at the things that take refuge in the shadows, in the background and in the night.

‘Social Hygiene’

This supremely clever feature by the Quebecois director Denis Côté wrings great comedy from a simple dissonance. On a grassy field in an unidentified locale, a petty thief, Antonin (Maxim Gaudette), is berated by a series of women — his sister, his wife, his mistress, a tax collector — in long, staged vignettes. The characters speak in dramatic, declamatory French, as if in a 19th-century play, and their costumes range from corseted dresses and shabby tailcoats to power suits and leather jackets. Yet the content of their conversations is contemporary and drably banal, dotted with references to Facebook, Volkswagens and discount mattresses.

Full of great quips (“I have so many debts, it’s like I have friends”), “Social Hygiene” milks these arch incongruities for an extended gag about the chasms between art and life. Though Antonin fashions himself as a tormented literary protagonist — a scrupled thief and a thwarted artist — he emerges as little more than a posturing, self-pitying millennial unwilling to take charge of his life. An air of phoniness looms over the characters, who appear like marionettes in Coté’s cool, distant tableaux. When we finally see them up-close, their faces fill the screen, but they seem even smaller — regular folks playing at being heroes and victims.

‘Zana’

Stream it on Tubi and Amazon Prime Video.

This gutting Kosovan film opens with a scene straight from the horror textbook: While leading a cow through the woods, Lume (Adriana Matoshi), a young, married woman living on a farm in the countryside, stumbles suddenly upon a bloodied bovine skull. As “Zana” unfolds, however, its genre stylings — austere visuals, blurred lines between nightmares and reality, pastoral gore and folklore — give way to the real historical terror pulsating underneath.

Lume, we learn, lost her 4-year-old daughter in the Kosovo War, which resulted in thousands of civilian casualties. She has been unable to conceive since, much to the chagrin of her mother-in-law, who drags her to healers and doctors, and threatens to find Lume’s husband a second wife. The director Antoneta Kastrati lost her own mother and sister in the war, and here she crafts a remarkable portrait of a community struggling to process unimaginable trauma. Lume’s crippling grief is dismissed as demonic possession by her in-laws and parents, who displace their own sense of loss into the desperate desire for a new generation. Matoshi turns in a formidable performance as a woman who has no words for the pain she so acutely feels, bearing the brunt of not just her own anguish, but everyone else’s, too.

In 2005, the ITAS machine parts factory in Croatia became the site for a monumental event. For decades, the institution had been state-funded but worker-managed, with employees owning shares and governing themselves democratically. When efforts were made to privatize the factory, the staff took over and insisted on continuing a system of joint and equitable ownership, in what became the first successful occupation of a European factory by its workers.

In the documentary “Factory to the Workers,” the director Srdjan Kovacevic visits ITAS 10 years after the takeover to capture its inner workings and outward challenges in a new, ruthlessly capitalist Europe. Assembling footage shot within the factory across five years, Kovacevic crafts a remarkable, fly-on-the-wall portrait of the workers’ labor, relationships and self-fashioned bureaucracy. Competition from corporations has shrunk the factory’s revenue, resulting in a vicious cycle of delayed salaries and lower morale, and culminating in a tumultuous leadership change. Unfolding like a thriller, the film is both cynical and galvanizing with its striking reminder that it takes a crowd — or rather, a collective — to make any kind of dent in this world.

‘The Substitute’

This Argentine drama might seem, at first glance, to be another entry in a hackneyed, often misguided genre: films about fish-out-of-water teachers trying to make a difference in inner-city schools. But “The Substitute,” directed by Diego Lerman, adds new dimensions to a cinematic cliché.

Lucio (Juan Minujín), a prestigious novelist subbing as a literature teacher at a local school, is indeed miles apart in life circumstances from his teenage students. They are embroiled in the violent intrigues of drug lords and corrupt politicians; his main concern, on the other hand, is to get his 12-year-old daughter, who is dealing poorly with her parents’ divorce, into a fancy school.

But “The Substitute,” crucially, is not about Lucio’s pedagogic brilliance or the transformative power of books; the scenes of him lecturing in class are almost comically uninspired. Rather, Lucio slowly realizes that his real contribution to his students is in being an ally to them in life rather than in school — which means getting his hands dirty in ways he’s always sought to avoid. With a sensitive lead turn by Minujín, “The Substitute” remains elusive and prickly all the way through, mimicking the messiness of reality more so than the neat arcs of stories.