European leaders complained for years that the United States was not doing enough to fight climate change. Now that the Biden administration has devoted hundreds of billions of dollars to that cause, many Europeans are complaining that the United States is going about it the wrong way.

That new critique is born of a deep fear in Germany, France, Britain and other European countries that Washington’s approach will hurt the allies it ought to be working with, luring away much of the new investments in electric car and battery factories not already destined for China, South Korea and other Asian countries.

That concern is the main reason some European leaders, including Germany’s second-highest-ranking official, Robert Habeck, have beaten a path to Vasteras, a city about 60 miles from Stockholm that is best known for a Viking burial mound and a Gothic cathedral.

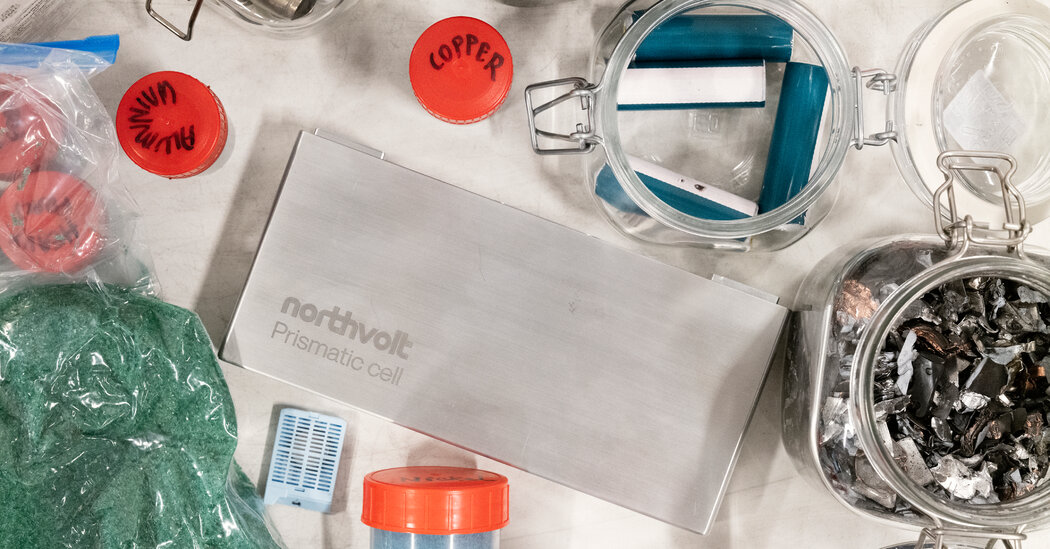

Officials have been traveling there to court one of Europe’s few homegrown battery companies, Northvolt. Led by a former Tesla executive, Northvolt is a small player in the global battery industry, but European leaders are offering it hundreds of millions of euros to build factories in Europe. Mr. Habeck visited in February to lobby the company to push ahead on its plan to build a factory near Hamburg, Germany. The company had considered postponing to invest in the United States instead.

“It’s definitely attractive to be in America right now,” Emma Nehrenheim, Northvolt’s chief environmental officer, said in an interview last month in Vasteras. Northvolt declined to comment in detail on the discussions about the Hamburg plant, which the company committed to in May.

The tussle over Northvolt’s plans is an example of the intense and, some European officials say, counterproductive competition between the United States and Europe as they try to acquire the building blocks of electric vehicle manufacturing to avoid becoming dependent on China, which dominates the battery supply chain.

Auto experts said that the tax credits and other incentives offered by President Biden’s main climate policy, the Inflation Reduction Act, had siphoned some investment from Europe and put pressure on European countries to offer their own incentives.

The United States has provoked a “massive subsidy race,” Cecilia Malmstrom, a former European trade commissioner, said during a panel discussion last month at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington. She called on leaders to “jointly invest in the green transition and not compete against each other.”

Biden officials have argued that U.S. and European policies are complementary. They have noted that the government and private money going into electric cars and batteries would lower prices for car buyers and put more emission-free vehicles on the road.

U.S. officials add that construction of battery factories and plants to process lithium and other materials is booming on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean.

Efforts by governments to promote electric vehicles “will spur a degree of technological innovation and cost cutting that will be beneficial not only to Europe and the United States, but to the global economy and to our global effort to meet the challenge that climate change presents,” Wally Adeyemo, the deputy Treasury secretary, said in a recent interview.

The Biden administration has also been talking with European officials about allowing cars made from European battery materials and components to qualify for U.S. tax credits. And the administration has interpreted the I.R.A., which Mr. Biden signed in August, to leave room for producers in Europe and elsewhere to benefit.

“You’re seeing less of a concern from Europe that those companies may be lured away from Europe to America,” said Abigail Wulf, who directs the Center for Critical Minerals Strategy at SAFE, a nonprofit organization.

Still, the law has forced European leaders to put new industrial policies in place.

In March, the European Commission, the administrative arm of the European Union, proposed the Critical Raw Materials Act, legislation to ensure supplies of lithium, nickel and other battery materials. One piece of the legislation calls for the E.U. to process at least 40 percent of the raw materials that the car industry needs within its own borders. The 27-nation alliance has also let countries provide more financial support to suppliers and manufacturers.

The money that the United States and Europe are pouring into electric vehicles will encourage sales, said Julia Poliscanova, a senior director at Transport & Environment, an advocacy group in Brussels. The legislation, which will need the approval of the European Parliament and the leaders of E.U. countries, would also bring some coherence to the fragmented policies of national governments, she said.

But Ms. Poliscanova added that European and U.S. policies risk canceling each other out. “Because everyone is scaling up at the same time, it’s a zero-sum game,” she said.

Business executives have complained that applying for financial aid in Europe is bureaucratic and slow. The Inflation Reduction Act, with its emphasis on tax credits, is simpler and faster, said Tom Einar Jensen, chief executive of the battery maker Freyr, which is building a factory in Mo i Rana, in northern Norway, and has plans to construct more plants in Finland and near Atlanta.

The I.R.A. has prompted “a dramatic increase in uptick in interest for batteries produced in the U.S.,” Mr. Jensen said in an interview.

The future of European auto manufacturing is at stake, particularly for German companies. Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Volkswagen have already lost market share in China to local automakers like BYD. Chinese automakers, including BYD and SAIC, are also making inroads in Europe. Selling cars under the British brand MG, SAIC has amassed 5 percent of the European electric vehicle market, putting it ahead of Toyota and Ford in that fast-growing segment.

European carmakers are frantically trying to build the supply chains they need to churn out electric vehicles.

In France, President Emmanuel Macron wants to convert a northern region where factory jobs have been in decline into a hub of battery production.

On Tuesday, Automotive Cells Company, a joint venture between Stellantis, Mercedes-Benz and TotalEnergies, inaugurated a factory in Billy-Berclau Douvrin, France, that aims to produce 300,000 electric batteries annually by the end of 2024. A.C.C. also plans to invest a total of 7.3 billion euros, or $7.8 billion, in Europe, including opening factories in Germany and in Italy, a deal sealed with 1.3 billion euros in public aid.

In Salzgitter, Germany, some 25 miles from Volkswagen’s headquarters, steel beams tower above concrete foundations as excavators and dump trucks hum nearby. In a matter of months, the outlines of a battery factory have risen out of a field.

Volkswagen hopes to have battery-making machines installed before the end of the summer. By 2025, the automaker aims to produce battery cells for up to 500,000 electric vehicles a year — a timeline that the company said was possible only because the factory was being built on land it owned.

Volkswagen is also building a factory in Ontario, but the company made the decision to do so only after the Canadian government matched U.S. incentives.

In Guben, a small city on Germany’s border with Poland, Rock Tech Lithium, a Canadian company, is building a plant to process lithium ore. Mercedes has an agreement with Rock Tech to supply lithium to its battery producers.

These projects won’t reach full production for several years. Recently, the Guben site was an open field. The only construction activity was a truck that dumped loads of crushed rock, making an ear-piercing screech.

Europe has some advantages, including a strong demand for electric cars: About 14 percent of new cars sold in the E.U. in the first three months of this year were battery powered, according to Schmidt Automotive Research, twice as many as in the United States.

But if Europe doesn’t move quickly to aid the battery industry, “you will really lose momentum on the ground versus the North American market,” said Dirk Harbecke, chief executive of Rock Tech.

Chinese battery companies have largely avoided the United States for fear of a political backlash. But Chinese battery firms have announced investments in Europe worth $17.5 billion since 2018, according to the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the Rhodium Group.

Political tension between Western governments and China has put German carmakers in a delicate position. They do not want to be overly dependent on Chinese supplies, but they cannot afford to displease the Chinese government.

BMW, Volkswagen and Volvo plan to buy cells from a factory in Arnstadt, Germany, run by CATL, a Chinese company that is currently the world’s largest maker of electric vehicle batteries.

To balance their reliance on Chinese suppliers, European executives and leaders are keen to work with Northvolt, whose chief executive, Peter Carlsson, oversaw Tesla’s supply chain for more than four years.

Northvolt wants to control all the steps of making batteries, including refining lithium and recycling old cells. That should help Europe achieve supply chain independence and ensure that batteries are produced in the most environmentally responsible way possible, said Ms. Nehrenheim, who is also a member of the Northvolt management board. “We’re de-risking Europe,” she said.

The company develops manufacturing techniques at its complex in Vasteras. Northvolt’s first full-scale factory, at a site in Sweden 125 miles south of the Arctic Circle chosen for its abundant hydropower, is the size of the Pentagon. Northvolt also plans to build a U.S. factory, but has not yet announced a site.

Still, the company is ramping up production and is not among the world’s top 10 battery suppliers, according to SNE Research, a consulting firm. And construction on its Hamburg plant is on hold until E.U. officials approve German subsidies.

Ana Swanson and Liz Alderman contributed reporting.