The proliferation of documentaries on streaming services makes it difficult to choose what to watch. Each month, we’ll choose three nonfiction films — classics, overlooked recent docs and more — that will reward your time.

‘Primary’ (1960)

Stream it on the Criterion Channel and Max. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Google Play and Vudu.

The run-up to the presidential primary season is (somehow, already) underway. To see how different the nominating process once was, get a look at Robert Drew’s pioneering documentary.

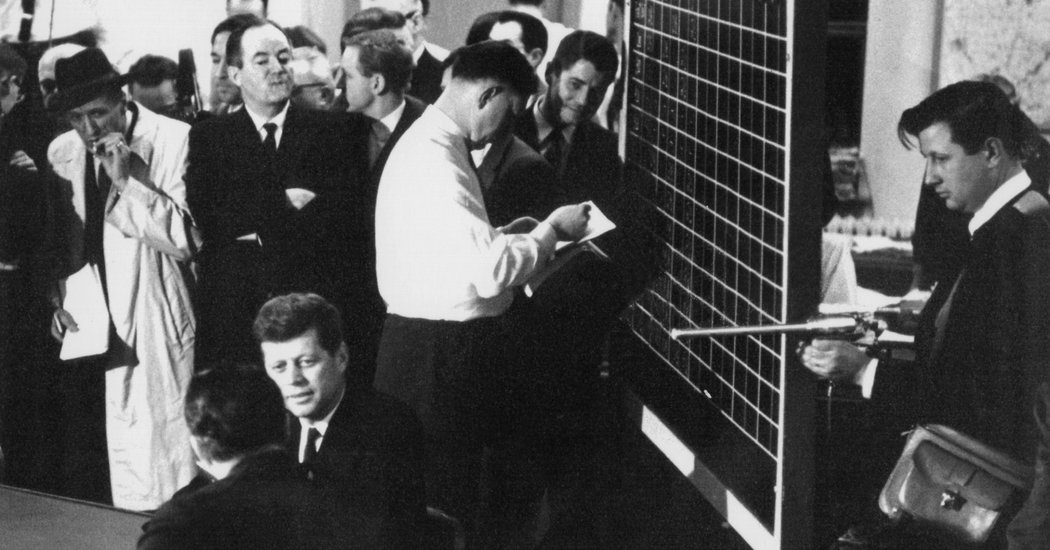

The film has to be watched through the prism of its time. Doubly disorienting, it is a chronicle of the 1960 Democratic presidential primary in Wisconsin at a point when the majority of states did not yet hold primaries; it is also a fly-on-the-wall documentary from a moment when that form — made possible by the increased portability of cameras and sound equipment — was brand-new. While sitting in the room with John F. Kennedy, then the junior senator from Massachusetts, as he receives news of election returns may seem like the sort of sight you could easily catch on TV today, in 1960 it was an innovative, close-range portrait, offering “an intimate view of the candidates themselves,” as the film’s opening narration puts it.

Kennedy ran against his fellow senator Hubert H. Humphrey, of Minnesota, who during the events of “Primary” was campaigning only one state away from his home turf. His advantage is said to be with rural voters; Kennedy has strength in cities. The barnstorming seems oddly wholesome and congenial by today’s standards. The film shows Humphrey pitching a room of farmers on how the Senate votes he’s taken aren’t popular in Boston or New York. Elsewhere, cheering crowds greet Kennedy and sing along with his campaign song, a reworked version of Frank Sinatra’s “High Hopes.” And although much of “Primary” consists of speeches and handshaking, it gives the sense of having captured the national conversation in microcosm. Some voters express the fear that Kennedy’s Catholicism would influence his politics. One woman says she favors him precisely because he is Catholic.

Drew, who takes a “conceived & produced” credit as opposed to calling himself a director, went on to make other films with Kennedy, such as “Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment,” which followed the Kennedy administration’s actions to support the integration of the University of Alabama in 1963. “Primary” may end with its two candidates on roughly even national standing from where they started, but it inaugurated the direct-cinema movement. People who worked on it — including Albert Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker as cameramen — went on to make groundbreaking documentaries of their own.

‘4 Little Girls’ (1997)

Stream it on Max. Rent it on Amazon, Apple TV, Google Play and Vudu.

Next month will mark 60 years since the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., an act of terrorism that killed four girls. Their deaths, Walter Cronkite says in an interview in Spike Lee’s moving documentary, became an “awakening” for Americans who had, until that point, failed to understand “the real nature of the hate that was preventing integration.”

Lee’s documentary, edited by Sam Pollard (“MLK/FBI”), leads by honoring the victims. The film opens with Joan Baez singing “Birmingham Sunday,” written in response to the bombing, over images of the graves and faces of the four girls, Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Rosamond Robertson and Cynthia Wesley. We then hear recollections from friends and family members who knew them. McNair’s parents, Maxine and Chris, recall how painful it was to explain to Denise, at around age 6 (she died at 11), why she wasn’t allowed to order from a lunch counter. A friend of Wesley’s, Dr. Freeman A. Hrabowski III, remembers Wesley’s sense of humor and kindness, and how they parted with the words “see you Monday,” not knowing what that Sunday would bring.

“4 Little Girls” also features interviews with civil rights leaders like the Rev. Andrew Young and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, who walks viewers through how he barely survived another bombing in 1956. (The commentators, billed as “witnesses” in the credits, include Howell Raines, the executive editor of The New York Times from 2001 to 2003, who wrote extensively about the events.)

But almost unavoidably, Lee’s most memorable interview is with the former Alabama governor George Wallace, a proud segregationist who now claims that his “best friend is a Black friend.” He insists on bringing his aide, Eddie Holcey, before the camera. “Ed come over here, just one minute,” he says. “Here’s one of my best friends right here.” Holcey, whom Wallace barely seems to look at directly, and who glances offscreen to make a sort of eyeroll, appears profoundly irritated at how Wallace is using him.

‘Geographies of Solitude’ (2023)

Rent it on Apple TV, Google Play and Vudu.

The naturalist Zoe Lucas first visited Sable Island — a beachy strip that is less than one mile wide, and that lies 100 miles off the coast of mainland Nova Scotia — in 1971. Since then, she has become a tireless and largely solitary cataloger of life on the island: its hundreds of wild horses, its invertebrates and its seabirds, among other animals. She is heard discussing the possibility of finding species that don’t exist anywhere else. The diets of the birds, who have a tendency to eat plastic, are one indicator of levels of pollution in the ocean, another trend that Lucas tracks.

In “Geographies of Solitude,” the filmmaker Jacquelyn Mills, while not a naturalist (to be fair, she is credited as director, editor, cinematographer, sound recordist and producer), takes an approach to this documentary that is, in its way, similar to Lucas’s. Both women see boundless possibilities in the island’s treasures. Mills draws on natural elements to make cameraless short films that wouldn’t be out of place in a Stan Brakhage retrospective. With a contact microphone, she and Zoe record the sounds made by the wood of a decaying A-frame on the island. She finds out what happens to film stock when it is buried in horse dung. She hand-processes film in seaweed and electronically renders music out of the crawling of a Sable ant.

Mills’s work is interspersed throughout the movie, which becomes a striking combination of environmental documentary and profile. It’s also a landscape film that makes a real effort to attune viewers to sights and sounds, and that gently dips its toe into the avant-garde. Late in the film, Lucas says it appears that her life is Sable Island — “that’s all I have, that’s all I do, all the time,” she notes, adding, with a hint of regret, “I lost track of everything else.” “Geographies of Solitude” isn’t quite immersive enough to make that happen. But it captures a world where cameras seldom go.