Maya S. Cade is the creator and curator of Black Film Archive and a scholar in-residence at the Library of Congress. In this personal reflection, she shares her journey to creating a new space for Black cinema and her connection to the artists and histories before her.

As a child, my maternal grandmother took great pleasure in having me guess what my birthday present would be. I would offer every childhood fantasy I could conjure.

Ruby Dee and Sidney Poitier in the stage production of “A Raisin in the Sun.” The New York Public Library.

“Barbies?” “Not quite…” she would respond.

“$100?” “I have something better for you.”

“A new book?” “No, something better.”

This game would go on until I wore myself out. Eventually, the gift would be revealed: a handwritten card where she scribed a blessing for my new year and intricately wrapped dollar bill crafts that would total my new age. She would hand the gift to me with a vocal reminder that there is no greater gift than doing things with love. She expressed that love from family and community will be there when the novelty of a new toy wears off.

To love and be loved as a Black person in America has always been intrinsically linked to community and the promise that love can help see us through as we attempt to survive – racism and all of its vicious cousins and offspring. In every Black history – shared or personal – there is a thread of love that allows us to conjure visions of survival and transformation. In telling me to trust love, my grandma passed on deep-seated knowledge: leading with love will unlock unlimited possibilities for my life as it had unlocked in the generations before me.

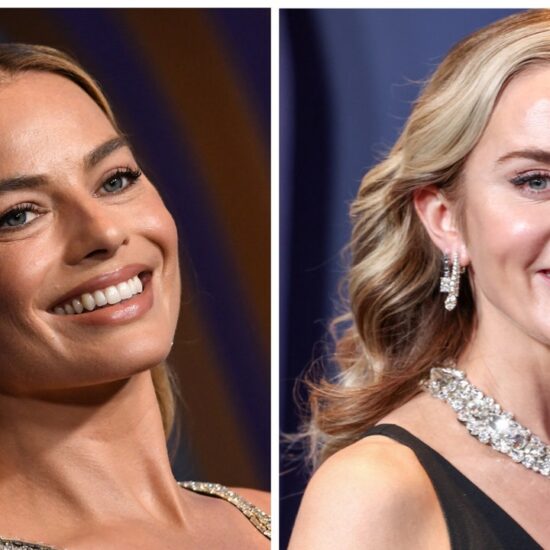

Film, and an utter fascination with all media, has been a deep love in my life for as long as I can remember. My first filmic obsession was “The Wiz” (1978), the exuberant reimagination of “The Wizard of Oz” with an all-Black cast based on the Broadway show of the same name. In the maximalist swirls of color, Motown-infused music, and Dorothy’s journey home were the joys of seeing a cinematic world without translation. Loving “The Wiz” gave me the confidence to chart a course through Black cinema, guided by the stars. Sidney Poitier, the first star I steered to, showed me the rich legacy of Black actors making a way against all odds. In my world, Poitier was revered as a member of the Black family as a larger-than-life figure we prayed for before I knew the depth of his film stardom.

In the early days of the pandemic, I rewatched “The Wiz” – and other beloved classics like “For Love of Ivy” (1968) starring Poitier – on a daily loop, hoping to find new visions of home as the world shifted beneath our feet and as Diana Ross belted:

♪ When I think of home

I think of a place

Where there’s love overflowing. ♪

Amid my endless marathon of “The Wiz,” an omnipresent question emerged as Black people digitally and physically protested in the wake of George Floyd’s June 2020 death: How does film represent the weight of Black history, present and future? The weighty question and public pressure prompted streaming services to launch Black Lives Matter collections with the platforms’ existing Black films.

I charted a new course in June 2020 – as public discourse increasingly insinuated Black cinema’s past only offered trauma. I began building a digital project that directly addressed Black moviegoers’ concerns and desires to better understand Black film’s past. Instead of shaming people for what they did not know or have access to, I imagined a way to present and reconstruct an underseen film history. Starting as a viral Twitter thread, my work transformed into Black Film Archive, a register of Black cinema from 1898 to 1989, currently streaming with contextual language. Aiming to fill a void and build a foundation for Black cinema knowledge, Black Film Archive reframes and reignites the audience’s relationship to the past.

As J’Nai Bridges, noted opera singer, said during “American Masters: In the Making” as she considered the future of her craft in a post-George Floyd world, “When I think of giving up . . I think of what [the shoulders I stand on have] gone through and what roads they’ve paved and what doors they’ve opened so I can be here today doing what I love.”

Toni Morrison reminds us with her work that the past is always in process. When we analyze it, an infinite amount of information can be yielded. The fight for ‘fair’ Black visibility on screen is as old as the motion picture industry itself. For centuries, Black moviegoers and Black artists alike have been trying to calculate the perfect formula to display Black humanity on screen. The answer is not as simple as a singular formula of 2+2 equals ‘positive, perfect representation,’ but with knowledge of the past as a guide, we allow multi-layered performances of identity to shine.

In working on Black Film Archive for nearly three years, I’ve had to parse through the limited notions of Black cinema that are often placed upon the form from curators, distributors and white decision-makers. The rotating cycle of suppression and waves of limited amplification of Black cinema is tied to a history of wavering white investment in the form across time. How do I persevere on an uphill battle of this uncertain terrain and remain optimistic about Black cinema’s future?

My answer is in the same vein. I feel a deep kinship with the artists and histories displayed in Black Film Archive. Because they are an extension of my family, the love of sharing their stories will be there for me long after the novelty wears off for others.