Sometimes, the most terrifying thing in the world is being a kid. Too young to fully comprehend the complicated machinations of the world, and too small to protect oneself from threats both physical and emotional, childhood can be scary. Whether it’s monsters under the bed or screaming matches between parents, bullies at school or the crushing social anxiety of young romance, being a vulnerable kid is often painful, difficult, and confusing. This is probably why so many films are about coming-of-age, and so much media in the horror or supernatural genre draws on childhood to tell their stories.

The Black Phone is yet another one, and it’s a brutal depiction of childhood. In the film, Finney Shaw essentially suffers everything a kid can — one dead parent and one who’s drunk and abusive, very violent bullies, social anxiety with his crush, a sometimes scaredy-cat disposition, loneliness, and a lack of a friend group; he even opens the film costing his softball team the game. This barrage of suffering doesn’t compare to what’s in store for him though, after being kidnaped by a psychotic masked man known as The Grabber.

The Black Phone and the Violence of Childhood

Finney’s life, like The Black Phone, is pretty bleak and getting bleaker, but there are streaks of luminescence in this darkness. His sister Gwen is a shining beacon of hope in his dark world, a wonderfully multifaceted character who’s tough enough to cuss out cops and smash kids with rocks if they mess with her brother, but sweet enough to open her dollhouse and arrange her religious iconography every day to pray. She’s a wonderful character, protective of Finney and afraid of little in this cruel world except, perhaps, for her father, a wrecked nightmare of a man. A severely alcoholic and diseased person angry over the death of his wife, whom he sees in Gwen and can’t stand, Mr. Shaw uses violence to pathetically prop up what’s left of his rotten ego.

This is the crux of The Black Phone — violence as a human ritual for protection. In this small Denver suburb in 1978, the school bullies perennially beat up others to protect their status and pride, the drunken father engages in belt-whipping in a routine to protect his position of authority and fragile ego, Gwen uses violence to protect Finney, and so does Finney’s only friend in the world, Robin. (A key scene finds Robin beating the bloody viscera out of a bully, with Finney walking away in disgust). The Grabber uses an explicitly ritualized system of violence to protect his very sense of self and crumbling psyche. Interestingly, until the movie’s final scenes, The Grabber is practically the only character to not draw blood.

The Black Phone is Not a True Story But is True to Childhood

That’s because the world that writer/director Scott Derrickson and his frequent co-writer C. Robert Cargill (who both also worked with Ethan Hawke in Sinister) has painted in The Black Phone is a misanthropic and cruel one, perhaps needlessly so. However, there’s an argument to be made that the violence in this small town is exaggerated to represent how Finney feels as a child.

This might explain some leaps of logic in The Black Phone, small things which require a tight suspension of disbelief that allegories often use, like the fact that five children have gone missing in a very small town and yet there’s no curfew or heavy police presence on the streets for when a glaringly obvious, huge black van pulls up in broad daylight to abduct kids. Or how kids’ skulls are smashed with rocks or their faces bashed into a pulp without seemingly any ramifications or consequences. All of this means that, while not the most realistic film, The Black Phone uses its exaggerations to be true to the nature of a traumatic childhood.

The Allegorical Horror of The Black Phone

If it’s taken a while for this review to get to the horror of The Black Phone, that’s because the film does the same. Though it has a very engaging first half, the actual scares and horror elements of the film take a while to develop (though when they do, there are a few solid jump scares and some wonderfully creepy moments).

Those seeking a straight-up horror film might be a bit disappointed by the patience the film sometimes demands, because The Black Phone is horror the way The Sixth Sense was horror — using genre elements to tell a dramatic and often suspenseful story about childhood. The film feels more like Room remade by Stephen King (whose son, Joe Hill, actually wrote the short story it’s based on).

The allegorical nature of The Black Phone is made clear by its titular supernatural device. Antiquated and disconnected on the concrete walls of the bare basement in which Finney is held, the phone nonetheless rings. Through its dark receiver, Finney is able to communicate with the five dead boys that The Grabber has kidnaped; each one provides tips from their experience in the basement, helping Finney with clues, riddles, and objects they discovered during their stay.

Meanwhile, Gwen’s dreams give her hints about The Grabber, as the girl is imbued with the same ‘touched’ powers of her deceased mother (which is part of Mr. Shaw’s resentment of her). Though each dead victim and psychic dream leads to a frustrating impasse, they build up the suspense and come together ingeniously in the final sequences.

Scott Derrickson Uses Horror For Coming-of-Age

The finale of The Black Phone makes it clear that a lot of the film is a coming-of-age allegory about standing up for yourself and dealing with the world’s onslaught of threats; it’s about Finney coming to terms with his childhood. This is made clear by some similarities between the two different violent male adults in the film, The Grabber and Mr. Shaw, and the way they each hold a belt for punishment. The basement is symbolic of Finney’s childhood itself and is the basement every tortured, self-conscious, lonely kid has to metaphorically escape to grow up.

The Black Phone is Scott Derrickson’s escape from his own proverbial basement. The Doctor Strange director’s childhood town impacted him heavily, as he tells Wenlei Ma for an Australian news site. “I was inclined to tell a story like this, because I felt that I had a lot of work at reckoning with aspects of my past and the impact it had on my life and who I was becoming as a person.” Derrickson continues:

I grew up in an area of north Denver that was pretty violent, a lot of bullying, a lot of fighting, a lot of kids were bleeding all the time. It was also right after Ted Bundy had come through Colorado, killing people. And the Manson murders had just happened. When I was eight years old, my friend next door came knocking at my front door and said, ‘Somebody murdered my mum.’ The mother of my friend next door was murdered. And there was a lot of domestic violence, even in my own home and in the homes of a lot of these kids that I knew. Parents punished children much more aggressively, and so it was a very violent, scary kind of place to grow up in a lot of ways. And I tried to bring that environment realistically into the movie.

“The Black Phone is essentially about childhood trauma, and it really is about what that is like and what it feels like,” Derrickson says, and the world he and Cargill creates in The Black Phone helps process this expertly.

Ethan Hawke, Mason Thames, and Madeleine McGraw Are Amazing in The Black Phone

Of course, this kind of catharsis would only be personal and not an excellent film without the talent of so many people involved. The young Mason Thames leads the proceedings as Finney and does an incredible job, even when he has practically nothing to work with, alone in a sparse basement. His resolution and arc from cowardice to courage is perfectly expressed despite his surprisingly stoic face. Madeleine McGraw might just be the best part of The Black Phone as Gwen, a delightful combination of precociousness and innocence, suffering and strength. Whether she’s incongruously cussing out Jesus in her otherwise sweet prayers or fighting with her father, the young actor explodes in every scene she’s in.

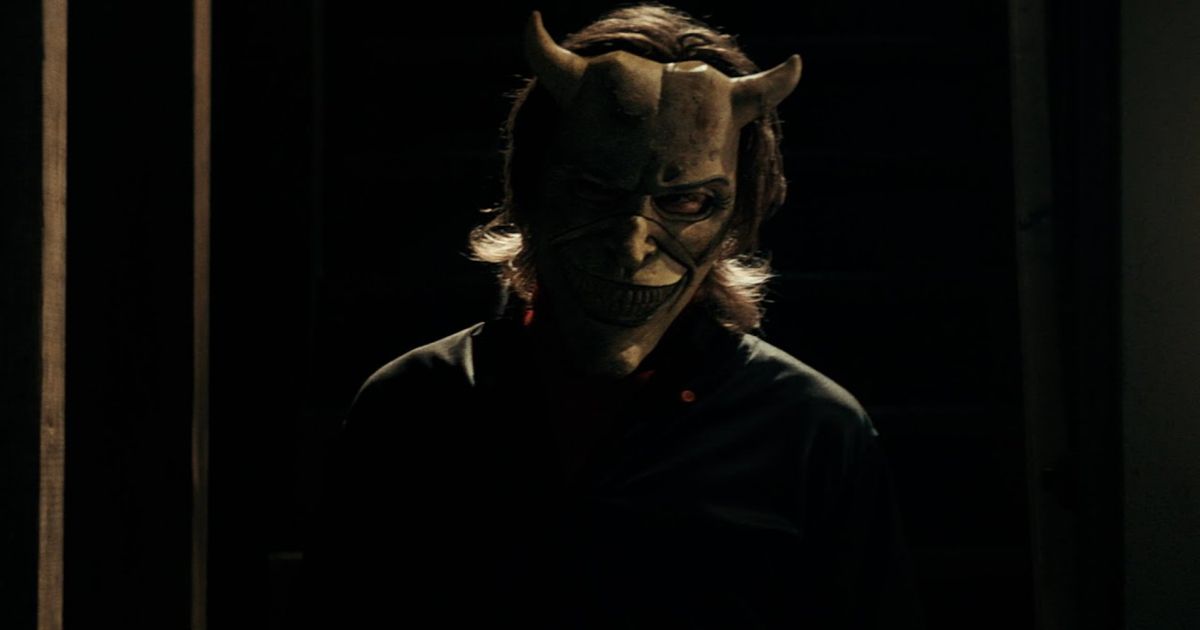

Then, of course, there’s Ethan Hawke as The Grabber. Much has been made of his performance and his recent turn to villainy in roles like this, Moon Knight, and Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets, and for good reason. While Hawke is obviously a master of his craft (and a great writer), it’s been fascinating to see him take on such menace recently. The actor was worried about playing villains, telling Entertainment Weekly, “I’ve always had this theory that when you teach an audience how to see the demon inside you, they don’t un-see it for the rest of your career.” While hopefully this isn’t true, it wouldn’t exactly be a negative thing to have more Hawke villains.

That’s because he’s amazing here. Hawke hides his face in a variety of ways behind a combination of masks with detachable parts designed by the great Tom Savini (who did make-up and effects for films such as Dawn of the Dead, Creepshow, Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and Friday the 13th). Nonetheless, Hawke’s great performance is incredibly expressive both physically and vocally, exuding psychotic menace with a kind of sick grace, but also childlike and unstable on occasion. With a long career as a true artist, it’d be presumptuous and perhaps unfair to say he’s at the top of his game here, but he’s close.

Hawke is the perfect manifestation of the horror Derickson wanted to exorcize. “Catharsis can come from using horror to confront the spoken or unspeakable evils in our lives, in ourselves, in our families, in strangers and nature, in the world. That’s what the genre is for; it’s all about in some ways confronting and facing what is frightening and traumatic in the world.” While there should be ‘think pieces’ on the arguably problematic conclusions The Black Phone comes to regarding violence and self-defense, the film itself is a great accomplishment. Wonderfully directed, expertly acted, and intelligently scripted, The Black Phone rings true.

From Universal Pictures, The Black Phone will be released theatrically on June 24th and can be streamed on Peacock 45 days after its release (August 8th).