Miles Warren’s narrative debut Bruiser is a restrained consideration of a familiar premise. Two men with shared history crave respect, approval and affection, but the asphyxiating confines of hyper-masculinity deter them from asking for it. They fight for domination instead, a quest that plagues their respective journeys with undercurrents of violence. Warren has a keen interest in trying to understand this path, in portraying what brutality does to individuals and their communities.

Bruiser chronicles the tumultuous summer between 7th and 8th grade for Darious (Jalyn Hall of Till), a recalcitrant teen struggling with puberty and life in his sleepy suburb. His mother, Monika (Shinelle Azoroh), spends most of her days conducting private violin lessons at home while his father, Malcolm (Shamier Anderson), sells cars at his dealership. With both of his parents working, Darious, whose relationship with his old friends has languished since he began attending boarding school, doesn’t know what to do with himself.

Bruiser

The Bottom Line

A mellow and compelling spin on a familiar story.

Cast: Trevente Rhodes, Shamier Anderson, Jalyn Hall, Shinelle Azoroh

Director: Miles Warren

Screenwriter: Miles Warren, Ben Medina

1 hour 37 minutes

The film, written by Warren and Ben Medina and screening at AFI Fest following its TIFF premiere, begins as a mellow observation of Darious’ fraught ties to his neighborhood, his parents and his peers. Cinematographer Justin Derry builds an arresting visual language from the first scene, in which we watch Monika pick up Darious from school. There’s a softness, an unobtrusive intimacy to each moment, the combinatory effect of close-ups and scenes bathed in a caramelized light.

During the car ride home, Darious would rather put in his earbuds than listen to his mother’s questions about his school crush or the car stereo blasting Otis Redding’s “Cigarettes and Coffee.” (The song becomes an auditory motif throughout the film.) The teen’s moodiness initially feels off-putting, but Hall’s performance — marked by slightly hunched shoulders, an avoidant gaze and a lilting voice — slowly reveals that the petulance is a sign of a complicated and tense emotional interiority.

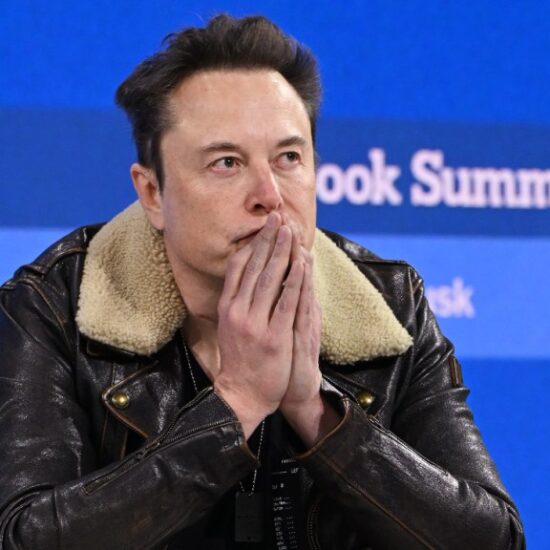

Darious, like most people his age, struggles to identify and express his emotions. His attempts translate to silence (as in the car with his mother) or temperamental outbursts. After getting into a fight with an old friend, Darious runs into the woods and stumbles upon a docked boathouse. Its owner, a stoic, muscular man, silently watches the bloody-lipped teen wash his face with creek water before approaching. The direct exchange — punctuated by deliberate but unawkward silences — sparks Darious’ curiosity about this mystery man named Porter (an excellent Trevante Rhodes).

Rhodes’ appearance onscreen naturally invites comparison to Moonlight, Barry Jenkins’ tender coming-of-age film that similarly negotiates the terms of masculinity. But whereas Moonlight also overtly grappled with sexuality and the formation of a queer identity, Bruiser strictly observes paternal bonds. Darious returns to Porter’s house more times over the summer, finding it easier to confide in him than he does his parents. The young teen confesses to feeling insecure, to worrying that his girlfriend at school no longer likes him and to feeling disconnected from his father.

Porter listens to Darious and only occasionally gives the young man advice. It soon becomes clear that Porter is not a stranger — to Darious or to his family. The revelation isn’t shocking, and Bruiser rightly doesn’t dwell on the fact of it. Instead, the film considers its effect: how Darious becomes trapped between Porter and Malcolm, who were best friends before their hatred of each other calcified. When Porter goes to Malcolm and Monika to ask to be in Darious’ life, Malcolm refuses to even engage. The latter can’t get past Porter’s mistakes, and makes it clear to his old friend that he doesn’t trust him.

The men represent two sides of the same coin. They both struggle with emotional regulation and self-expression — yet whereas Porter is honest about his challenges, Malcolm clings to respectability as a shield. Warren and Medina’s screenplay does tip into cliché, but avoids living in that territory by building out the inner lives of these two men. Instead of relying on expository speeches, Warren experiments with scene staging, camera angles, light and music to highlight Porter and Malcolm’s differences and similarities. Occasionally, Bruiser leans too heavily on Robert Ouyang Rusli’s beautifully sonorous score, but the attempt to connect the visual vocabulary to an auditory one is welcome.

Performances are what ultimately sets Bruiser apart as a debut and signal Warren’s potential as a director. This is a film whose action happens through conversations between the three central figures: Darious, Porter and Malcolm. Hall, Rhodes and Anderson deliver fine performances that allow their characters to maintain their allegorical functions without losing their dimensionality. Their exchanges are tinged with the hurt of old wounds and the hope of future forgiveness. We understand how these relationships are evolving from the way the actors position their bodies, look (or don’t look) at each other when the characters feel most vulnerable, or the way their voices change when they try to perform instead of engaging. That kind of care and detail create an investment in the story and the people that populate it, keeping us tethered and wondering about their decisions even after the credits roll.