In Verdi’s epic opera “La Forza del Destino” (“The Power of Destiny”), none of the characters can escape the inexorable drive toward a tragic ending. The director Mariusz Trelinski, originally a filmmaker by training, has identified one force in particular that determines the events.

“It is a story about patricide and the consequences,” he said by phone from Lyon, France, referring to the death of the Marquis of Calatrava. “The killing of the father in the first act determines the fate of all the characters. They are pushed like billiard balls and can only continue rolling passively.”

From Feb. 26 to March 29, Mr. Trelinski will mount the Metropolitan Opera’s first new staging of the opera in nearly three decades. It is a co-production with Teatr Wielki – Polish National Opera in Warsaw, where Mr. Trelinski serves as artistic director and where the production was first seen in January.

At the Met, the music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducts a cast including Lise Davidsen in her role debut as a Spanish noblewoman, Donna Leonora de Vargas, and Brian Jagde as her suitor, Don Alvaro, who is half Peruvian. Igor Golovatenko plays her brother Don Carlo de Vargas — whom Alvaro kills in a duel.

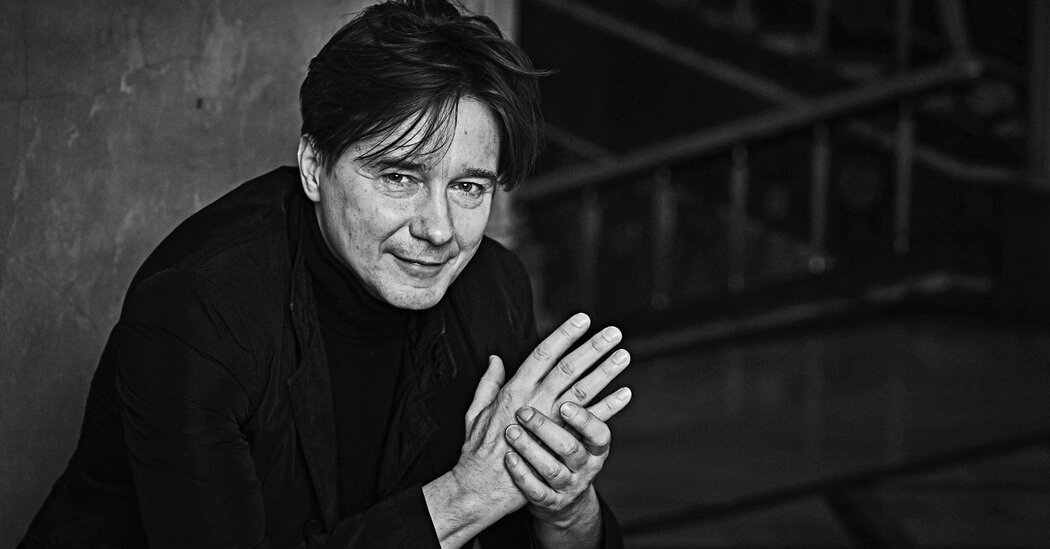

The relationship between Mr. Trelinski, 61, and the Met began in 2015 with a double bill of Bartok’s “Bluebeard’s Castle” and Tchaikovsky’s one-act opera, “Iolanta.” The next year, the Met’s season opened with his staging of Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde.” Both operas emerged in co-production with the Polish National Opera (“Tristan” was additionally mounted at the Baden-Baden Festival in Germany).

The director’s career in opera first took off with a 1999 production of Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly” that traveled from Warsaw to Washington and Los Angeles, followed by stops in Valencia, Spain; Tel Aviv; and St. Petersburg, Russia. Known for his contemporary but clear visual language, Mr. Trelinski was in 2018 named best director at the International Opera Awards in London.

The following interview has been edited and condensed.

You often approach your characters from a psychoanalytical perspective. Tell us more about your production of “La Forza del Destino.”

For me, Calatrava is the symbol of patriarchy. His assassination is a rejection of everything that has formed us: norms, laws and logos. After that moment, the characters become slaves of the situation.

It is an epic story that unfolds over about 20 years. We begin with Calatrava’s birthday party, where we see the elite of society and the prestige of military forces.

After that, war breaks out. We see that the world is turned upside-down. And in the third part, after so many years, we see the ruin of civilization. Our heroes are older and tired.

The set is in almost permanent motion, as a kind of metaphor for the mad rush of fate and events that you cannot stop. We cannot stop these wheels from turning until the end of our lives.

Does faith or God offer any promise of redemption?

Nowadays faith does not consist of the divine judgments we find in Verdi’s opera, but rather human complexes that are deeply inscribed in the fabric of life. The result is broken lives, children searching for a kind of surrogate father, and a series of false unconscious choices.

This is the reason Leonora takes refuge in a monastery and Alvaro joins the army. They choose a surrogate father because these are patriarchal institutions. We cast the same singer [Soloman Howard] as Calatrava and the superior of the monastery, Padre Guardiano, to drive home this principle.

And true love has no chance in these societal structures?

I think Verdi’s answer is pessimistic. Love initially gives Leonora and Alvaro together hope for a different life. But patricide separates them for many years.

When they finally meet again, they see in each other the ones who killed the father. They both feel guilty and cannot live together.

Verdi is very clever here. The crime leaves behind such a wound that even love cannot really repair it.

I have staged “La Traviata,” where you also have a domineering father who represents patriarchal society. It was important for me to return to this opera and understand this as key to the story.

How has your relationship with the Met and [the general manager] Peter Gelb evolved over the years?

I’m very happy with the trust we’ve built. And I think a big part of it is my filmic approach. People today see the world through the eyes of cinema — they speak through pictures.

This is a key issue because what does it mean to be opera director? An opera director is somebody who can visualize the music.

The music really shows you the energy of the production, the tempo of the changes. And it’s always the truth, because there are a few librettos that are really great, but in, let’s say, 70 percent of operas, we have genius music, and the libretto is secondary. And if we want to bring this genre to life, we have to keep this in mind, because the music is eternal.