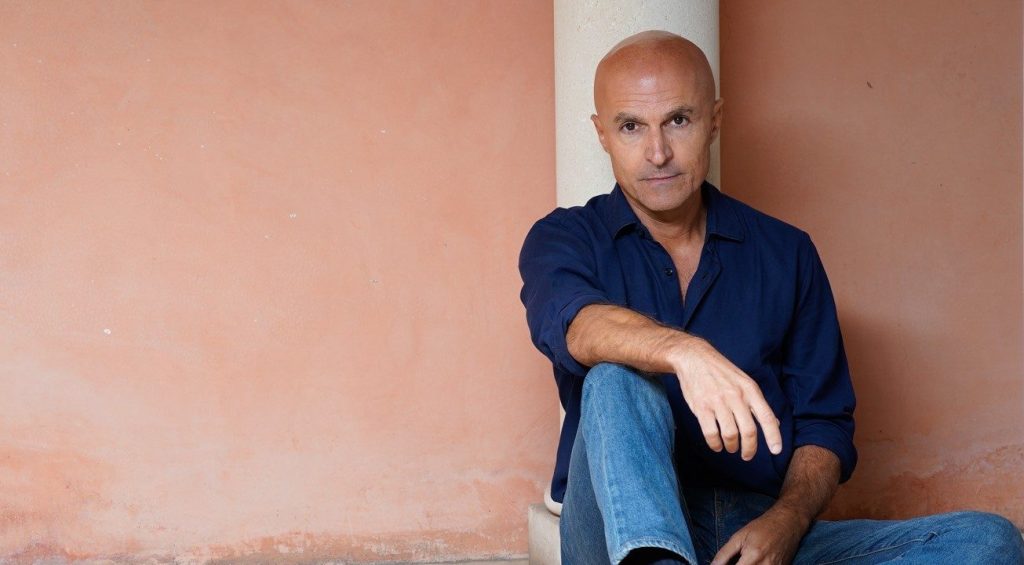

EXCLUSIVE: It’s a scorching 90 degrees in Rome at the end of July, but producer Lorenzo Mieli isn’t breaking a sweat.

In the course of three days, he’s fully booked, first working into the night with Luca Guadagnino on the filmmaker’s new Daniel Craig movie, Queer, which wrapped shooting in June at Rome’s Cinecittà. Then Mieli’s presence is required in Naples the next day on the set of Paolo Sorrentino’s new movie, tentatively titled Parthenope. There’s talk of the production shooting on the water — which is always complicated for any movie. While there were ocean shots in Sorrentino’s Oscar nominated international film, Hand of God, what’s required here on Parthenope is a whole other level. Then Mieli will make a pitstop on the fourth and final season of the HBO series My Brilliant Friend in Caserta, outside Naples, which he executive produces.

Lorenzo Mieli

Riccardo Ghilardi

Being on the air-conditioned train to Guadagnino’s historic estate Villa La Ceriana in the Piedmont countryside keeps the multi-faceted Mieli cool in the thick of a muggy Italian summer, and also allows him to roll calls.

The producer talks in a sotto voice and from what I can gather from his conversations during our trip to Guadagnino’s; there’s a phone call to the Oscar nominated filmmaker’s rep, CAA co-Chairman Bryan Lourd, then another call to an unnamed business contact, who Mieli implores: He wants to make sure that the director of his next movie, Without Blood, receives more than a fair share of points. That filmmaker Mieli is advocating on behalf of is Angelina Jolie, who is currently in post on her sixth feature-length directorial, based on the Alessandro Baricco novel of the same name, which was also shot at Cinecittà.

In an Italian film industry that’s looking to regain its footing from the glory days of exports such as the 1997 $230M-multi Oscar winner, Life Is Beautiful, and to yield a new era of filmmakers that rival both Neo-Realism legends such as Federico Fellini and auteurs such as Bernardo Bertolucci and Sergio Leone, Mieli stands as the catalyst to the country’s next cinema and TV renaissance with his production shingle The Apartment, which is one of the film labels owned by Fremantle that backs his pipeline and development.

Italian moviegoing for some decades has been in a funk with theaters greatly in need of repair, and attendance largely confined to the cities, with the marketplace weighted toward Hollywood films. Barbie is the year’s top grossing movie with over $35M per Comscore and the whole pink of it all has some Italian filmmakers up in arms; they just don’t get it. Despite a country wide moviegoing initiative which has spiked box office this summer, the Italian B.O. at $315.1M, while already set to best last year’s $322.8M, is still off from pre-pandemic highs such as 2010’s pinnacle of $948M. Meanwhile, if you’re an Italian filmmaker looking to make waves in local theaters, best to make a pithy family comedy. This trend put into effect during the Berlusconi Medusa and Cecchi Gori era of the 1990s to early aughts prompted Mieli to lead a charge of filmmakers to create premium quality fare for a global audience, one which is now putting Italy back on the map.

“Lorenzo is doing something that is unprecedented,” says Mieli’s collaborator of six films, Oscar nominated filmmaker Luca Guadagnino.

“Lorenzo’s quality has always been one of complete independence and experimental, which I feel I am as well. We find amusement in doing things that have never been done before, but also are very ambitious, which goes beyond the boundaries of Italian cinema, beyond the rules of the game in the Italian industry,” emphasizes Guadagnino.

“I have not thought about making films for this market since to be honest, since ever,” Guadagnino tells Deadline, making him a ripe partner for Mieli, “I want to be seen by as many people as possible and by as many identifies as possible.”

While other Italian producers in the 1980s and 1990s may have made Italian films that were able to travel, Cinecittà CEO Nicola Maccanico says that Mieli, who has shot several projects on the historic Rome lot, “is much more a contemporary producer in which globalization takes effects; he’s built international productions for the international market.”

Sabrina Lantos

To that point, Mieli is having a milestone fall film festival season with as many as five premieres between the Venice Film Festival and Toronto International Film Festival, the most ever for the producer in his near two-decades career. On Monday night, Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla will make its grand global debut at the Sala Grande at Venice. It’s a big deal as Priscilla, reps the first of two movies from Hollywood filmmakers that Mieli is producing.

‘Adagio’

Emanuela Scarpa

Also at Venice was Stefano Sollima’s crime thriller pic Adagio about a trio of impaired gangsters who square off with the cops. Deadline’s Damon Wise called the movie “a gripping call-back to the heyday of poliziotteschi movies, a peculiarly Italian genre that dealt with inter-gang wars in a country where the police were often more venal than the bad guys.”

In addition, on the Lido, Mieli had Pietro Castellitto’s Enea, about the hijinks of two young men, Enea and Valentino, which is set against the hedonist backdrop of drugs and parties. Call it Bret Eaton Ellis, Italian style. The movie in addition to Queer, Bones and All, Challengers, We Are Who We Are, and Holiday is among Mieli’s six collaborations with Guadagnino, who also produces, and counting.

‘I Told You So’

At TIFF, Mieli’s The Apartment label has Ginerva Eklann’s feature, I Told You So, in competition which stars Danny Huston, Greta Scacchi, Alba Rohrwacher, and Valeria Golino in what’s billed as a romp in Rome during an unprecedented heat wave that follows the idiosyncrasies of a ragtag group of people comprsed of a single mom, a bankrupt porn star, a heroin addicted priest, among others.

Holiday

There’s also Edoardo Gabriellini’s Holiday, another co-production between The Apartment and Guadagnino’s Frenesy, in TIFF’s Centerpiece section. The movie follows near twentysomething Veronica (Margherita Corradi) who is released from prison, after she was accused of brutally murdering her mother and her mother’s lover. Now a social pariah, she is beating a drum in search of a fugitive while trying to reclaim her youth.

Luca Marinelli as Benito Mussolini in the Joe Wright directed series ‘M. Il figlio del secolo’

Fremantle

Duly note, Mieli has already made waves on HBO with his series exports The Young Pope, The New Pope, Guadagnino’s We Are Who We Are, and the award-winning My Brilliant Friend, and he’s in post on the upcoming, audacious eight-episode Joe Wright-directed series about Benito Mussolini, M. Il figlio del secolo, which is out to U.S. buyers. If there was ever a mirror to these divided political times where demagogues rule with the sway to impel crowds to storm a capital, it’s M.

The idea of an Italian producer, at least for Hollywood, conjures up sensational legends, whether it’s the high-rolling, buck-stops-here producer of gawdy epic fare like Dune and Conan the Barbarian, Dino De Laurentiis, who was known to lord over filmmakers’ visions and tell actors which projects they should take or pass on. Or Carlo Ponti, who was not only known for big splashy titles like Dr. Zhivago, but being the right arm and champion of wife Sophia Loren, an EP on her Hollywood films from 1956 to the early 1960s. Then there’s the Cecchi Gori family, who built an enormous library of films–largely local Italian comedies, dotted with a few Oscar winners such as Life is Beautiful, Mediterraneo and Il Postino. However, the dynasty descended into bankruptcy and financial ruin by 2006.

Mieli is an anomaly next to the larger-than-life reputations of these titans, a modest, Zen-spirit, whose m.o. is to be filmmaker-friendly first, seeing eye-to-eye with their visions, as he develops, packages and structures financing for their series and films, all of which are intended to appeal to a global audience, even if it’s in a Neapolitan dialect that’s subtitled for Italian audiences, read his HBO hit My Brilliant Friend.

Or as Guadagnino calls Mieli, “A diplomat.”

“The business is about creating a mutual trust,” Mieli explains about his style, “I approach filmmakers that I don’t just love, but that I know we can discuss things, that we’ll have the same common language.”

“They need to feel that you understand what they want, and what they’re trying to do,” continues Mieli on our train ride to Guadagnino’s.

“If I give them the freedom, they will listen,” says the producer when it comes to having those chats about art versus commerce with filmmakers, particularly in the editing room.

Given how Mieli is consumed with the financial brass tacks and script development side, he specifically tells me, “I don’t like to be on set.”

And there’s a reason for that.

“Only the director can solve the problem to go in a new direction,” Mieli says about any given project, “I never want the director to feel anxiety during the shoot.”

So, not Dino.

And it’s only in rare circumstances, Mieli will step in. In the case of heading down to Sorrentino’s Parthenope, he tells me days later after that visit “the production schedule was changing so I went down to reshape it; normal things that happen during production.” The movie is inspired by the Greek myth of the siren who failed to entice Odysseus with her songs, and who cast herself into the sea and drowned. Her body washed up on a symbolic rock where Naples is built. The pic, which stars Gary Oldman, Luisa Ranieri, Silvio Orlando, Stefania Sandrelli, Isabella Ferrari, Peppe Lanzetta, Alfonso Santagata, Lorenzo Gleijeses, Silvia Degrandi and newcomer Celeste Dalla Porta; is neither about a myth or siren, rather a woman, Parthenope, and her relationships.

Joe Wright, far right, directing the upcoming Mussolini TV series ‘M. Il figlio del secolo’

Andrea Pirrello

Expounds Wright, who first met Mieli at Deadline Hollywood’s Contenders NYC 2021, when the latter first approached him about directing M. Il figlio del secolo, adapted by Gomorrah scribe Stefano Bises from the Antonio Scurati novel, “He allows himself a little bit of a distance to be able to see more objectively, and that’s really useful.”

Wright, a fervent fan of Gomorrah, was bowled over about Mieli attaching him to M. “That was really interesting, a left field idea, and a smart one given my distance from the material.” The passion for Mussolini to some older generation Italians isn’t far from modern day Americans’ penchant for Donald Trump. “It’s a very emotional issue for Italians,” Wright says. Mieli took to Wright given his work on The Darkest Hour. Wright sprung to the gritty project, which displays Il Duce warts-and-all as a sex-fiend, for its morality tale on how populism powers politics.

Wright observed Mieli’s razor-sharp development notes, which aren’t bogged down in the “nitty gritty”. “He had one idea at the beginning, and this is a spoiler, but it turned the whole project around, and you just went ‘Oh my God, that’s the line!’ and that is Lorenzo.”

Adds Coppola, whose Priscilla was mounted by Mieli, “He really respects a director, and I felt he was really interested in what I wanted, not pushing his agenda.”

Says Francesca Orsi, HBO’s Head of Drama, who launched My Brilliant Friend with Mieli, “The truth is he’s a deep intellect, but he also understands the more common man or woman; the populist if you will. He has the finger on what people want without being pretentious about what he executes as a producer. He has a very sophisticated taste and you can see that across the work he’s immersed in, but he himself, is a man of the people.”

‘Challengers’ (L-R) Mike Faist, Zendaya and Josh O’Connor

Metro Goldwyn Mayer Pictures

In an industry where success has many fathers, Mieli’s modesty is a rare breed, taking credit where only credit is due. Broach the subject of Guadagnino’s Challengers and he’s quick to say that the Zendaya project was driven by Amy Pascal; Mieli brought aboard as EP by Guadagnino to manage the Italian part of the spicy tennis player romance pic. As we arrive at Guadagnino’s castle, which looks like the house straight out of his Oscar-winning, Call Me by Your Name, it was only days prior that MGM moved the pic’s release date from mid-September to late April, and pulled it from its Venice world premiere given Zendaya’s unavailability to promote the film due to the SAG-AFTRA strike. The duo are bummed, but at the end of the day, they know it’s for the best of the film.

Once Upon a Time in the West

Everett

Once Upon a Time in Italia

Mieli grew up during the 1980s in Rome “obsessed by cinema and going alone to watch movies” as a teenager; an avid Martin Scorsese fan of such movies like Raging Bull and Taxi Driver. However, there was one movie which lingers with him to this day, one which would become imbedded in his philosophy toward the types of projects he mounts at The Apartment: Leone’s spaghetti western Once Upon a Time in the West.

The 1968 pic is one of Leone’s few that didn’t star Clint Eastwood, rather cast Henry Fonda against his good-guy type as the villain, with Charles Bronson as the good guy, Jason Robards as a bandit and Claudia Cardinale as a newly widowed homesteader. For Italian filmmakers, the movie is akin to Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola and Scorsese partnering on a project: Check out the story credits and they’re by Bertolucci, Leone and Dario Argento.

“I was really fascinated by this guy, Leone, who never left Italy and was able to manage with this American thing, the western, using it as a mythology and changing it into something that you’ve never seen before without ever going to America. That’s something in a way I’d love to do today. My ideal world is to do something here that resonates with the international, the American mindset, but from a different position, from a different world, from a different angle.”

Fratelli dell’anima: Luca Guadagnino (R) and Lorenzo Mieli (L) at the premiere of “Bones And All” in Zurich last year.

As we catch up with Guadagnino after a lunch of spaghetti arrabbiatta in the cicada infused, sunflower filled summer eve, the filmmaker shares a similar sensibility with Mieli when it comes to art. It’s no wonder why they’re creative partners.

“I never really mingled with any of the producers in Italy; (though) I did have many great relationships with producers in Hollywood. But with Lorenzo, it’s different. First of all, we have a similar ambition. We’re really driven by the spirit of independence, but also we love the cinema as a place without boundaries. So, we’re not limited to think of cinema from the perspective of where we are in Italy.”

BONES AND ALL, from left: Timothee Chalamet, Taylor Russell.

MGM /Courtesy Everett Collection

A prime example of that being last fall’s cannibal romance, Bones and All, directed by Guadagnino and starring his leading man Timothée Chalamet. The movie was both horror and romance, shot in the Midwest for around $20M, and like Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West, served up an Italian’s angle the U.S., specifically the 1980s Reagan era; Elliott Hostetter capturing the period nuance of the US countryside down to the dirty Greyhound bus station. With his editor Marco Costa, Guadagnino cut a riveting teaser, one which impassioned MGM Chairman Kevin Ulrich to take the film off the table from rival studios. Mieli put the financing together and orchestrated the sale. Bones and All won Guadagnino the Silver Lion at Venice, as well as actress Taylor Russell the Marcello Mastroianni Award. Bones and All was launched around Thanksgiving where it ultimately made $15M WW.

Mieli’s love of cinema encouraged him to pursue directing, and during the ’90s he did commercials and short movies, and was the second and third AD on sets. One filmmaker he worked for was Ermanno Olmi. However, it was an encounter with an enigmatic man in the Lincoln Center cafeteria during his student days in New York, that convinced Mieli to turn to producing; that directing wasn’t his bag. He returned to Italy, grabbed his friends and launched a production company. Many of those amici who he started his producing career with are still with Mieli at The Apartment, such as Gabriele Immirzi who is co-CEO of the Fremantle owned label, and Elena Recchia, who is the Head of Physical Production. In regards to learning the ins-and-outs of producing, Mieli never had a mentor. “It was really a practical experience-based learning curve,” Mieli says.

Fast-forward, to 2001, and Mieli established the shingle, Wilder, named after Billy Wilder. He navigated the Italian TV industry which was ruled by the duopoly of state broadcaster Rai and Silvio Berlusconi’s Mediaset, which later saw another giant get in on the action, Rupert Murdoch’s Sky Italia in 2003. In 2009, Mieli, then known for TV series, partnered with Mario Gianani, whose track record was in film under his company, Offside. The merger became known as Wildside, which was ultimately absorbed by FremantleMedia Italia. In 2010, Mieli was named CEO of FremantleMedia Italia.

‘The Young Pope’

HBO

While Mieli would get to work with Bertolucci prior to the Oscar winner’s death on the TV series Me and You based on the novel by Niccolò Ammaniti, which the producer secured the book rights to, it was the 2016 Jude Law HBO series The Young Pope, which Maccanico calls “a game changer, a project of great dimension” for the Italian entertainment industry.

“It was the first time I struggled to understand, to create new and different things, and financing was a difficult part of the job,” Mieli explains.

Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty had just won the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Mieli and Sorrentino longed to work together, but the latter had been collaborating with a different producer, not to mention Mieli’s focus was in TV.

How it all started per Sorrentino: “He pitched me a TV project on Padre Pio. I instinctively replied, ‘No, but I’d like to create a show about the first American pope as I imagine him: very young, handsome and a heavy-smoker”. Lorenzo said ‘yes’ right away.”

“I understood the magnitude of the show that I couldn’t make it with just Italian money, but European money,” says Mieli, “So, I said let’s try to do a TV series in the same way they made movie in the ’70s. Let’s include France, Germany and the U.S. So, I flew to LA for the first time and met with a few executives. No one there had ever invested money in an original TV series from Italy.”

Mieli owned all the scripts, having spent a year and half developing the project with Sorrentino, and had Law attached. The template of having all the creative essentials lined up would became a future business model by which Mieli would sell all his projects to the global market. While the series cost per episode in the single millions, HBO expressed concern initially about boarding the project, despite their adoration for it, as “they were scared of the fact that I had to shoot in a few weeks.” Mieli persuaded HBO that their risk wouldn’t be severe as they weren’t financing the show, just buying the license. HBO wound up taking U.S. and a few foreign territories. The New Pope, the follow-up series debuted in 2019.

Sorrentino further adds, “Lorenzo is invaluable in his script analysis and sharp in the editing room. During The Young Pope, he suggested unthinkable ideas and edits that seemed crazy to me at first. But when I eventually tried them, he was always right.”

Threading Ferrante

The Young Pope would bust the doors open for Mieli at HBO to bring in the series adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s bestselling four-novel series (10M copies sold in 40 countries), My Brilliant Friend; the fourth of which is currently being shot in Caserta.

My Brilliant Friend follows two girls–Elena and Lila– whose complicated friendship spans some 50 years, having initially met in their working class Naples neighborhood post WWII. The series is narrated by Elena aka Lenù, the character voiced by Rohrwacher.

Mieli found the books “empowering”.

“You don’t know who’s the brilliant friend out of the two of them. You always suspect that, it’s not the lead character, so it’s the other one. So, she’s weak. She reveals all the weakness, all the anger,” says the producer.

“On top of that, the whole book is about a woman who’s trying to become independent and escape from the place where she was born, and flee the cultural limits of that world, but from page one to the end of the books, she is hooked by horrible men, and she can’t escape that,” Mieli says.

Filmmaker Saverio Costanzo already had a working relationship with Mieli, the two having teamed on the Adam Driver 2014 romance film, Hungry Hearts. Costanzo initially wrote to the reclusive author for the film rights. Though he was unable to get the project off the ground as a feature, Ferrante later allowed him to adapt the books into a series. Ferrante is known to provide extensive, precise script notes by email, and her interface on such matters has only been with Costanzo, who keeps all of her correspondence reportedly in binders.

Mieli chased the rights on My Brilliant Friend, but learned that Domenico Procacci had them. Mieli convinced Procacci to partner so that they could mount a global show out of the books, and he accepted. Other producers were chasing hard after the books, and their popularity were on HBO’s radar. Orsi, for one, was familiar with Ferrante’s books having been referred to them by her mother, who is also from Naples. Initially selling the series in Italy proved a challenge as the series was subtitled in Italian given the show’s hard Neapolitan dialect, but RAI came through.

HBO made a deal with the producers in 2017. While one season was ordered, there were options for subsequent seasons. My Brilliant Friend catapulted HBO into the foreign language series space, which quickly became competitive with shows on rival streamers, i.e. Neflix’s Squid Game.

Orsi observing Mieli’s eloquent skillset as a producer, says “He navigates and facilitates various issues that we’re facing across budgets.”

Alba Rohrwacher, right, on season 4 of ‘My Brilliant Friend’

Fremantle

“Early on, we were coming to an agreement on exactly what the tone of My Brilliant Friend would be, having not worked with Saverio Costanzo before. Lorenzo stepped in such a comforting, reassuring way. There’s a real patriarchal, authoritative, calming, self-assured style to him that allows for any problem to get sorted out.”

“We were really able to assess what the tone would be with Saverio and ended up agreeing on casting, which at first was a complicated process when we were building the show. There were high stakes: We had never done a show in a foreign language before. The onus was on us to make sure we delivered. I was also new to running the division, so I felt a lot of pressure to succeed as one of the new heads of the drama department. So, everything I touched, I was careful with. Lorenzo helped me be successful.”

During Deadline’s set visit to My Brilliant Friend, it’s clear the production is running like clockwork in the hands of episodic director Laura Bispuri as she directs two little girls with Rohrwacher, who is finally making her appearance in the flesh as Lenù. There’s nothing necessary for Mieli to wrangle here per his credo of allowing creatives to do what they do. A faux multi-block old Naples town has been erected here on an empty lot, in addition to a warehouse that has several interiors from the show as well as thousands of props. As the clock winds down, crew members are melancholy after what has been a long journey. The set has also become something of a novel tourist attraction for global fans of the series.

Paisans

On Monday night, Venice Film Festival auds will get to see Coppola’s ninth feature directorial, Priscilla, based on the Priscilla Presley’s memoir Elvis and Me. Coppola met Mieli through her publicist Bumble Ward in the fall 2021. Initially, Coppola’s conversation with Mieli was about his financing her Edith Warton project, Custom of the Country, as the Oscar winning filmmaker wanted to shoot in Italy. However, the conversation turned to Priscilla.

Jacob Elordi, left, as Elvis, and Cailee Spaeny as Priscilla Presley in Sofia Coppola’s ‘Priscilla’, produced by Lorenzo Mieli.

A24

The project, though budgeted for less than $20M for a 30-day shoot, had its hurdles in its quest for funding back in the fall of 2021. The movie was following in the wake of Baz Luhrmann’s big Warner Bros take about Elvis (which would ultimately gross $288M-plus WW and land eight Oscar noms), and Graceland wasn’t granting the use of any music. Furthermore, Coppola had the cast set with Euphoria’s Jacob Elordi as the King of Rock n’ Roll and fresh face actress Cailee Spaeny. She shot the movie in October 2022 in Toronto. Mieli found a U.S. buyer in A24. Priscilla recently received a SAG-AFTRA interim agreement permitting its talent to promote during the strike given the pic’s Canadian shoot. The movie opens stateside Oct. 27 after its North American debut at the New York Film Festival on Oct. 6.

“I don’t think this movie would’ve happened if it weren’t for Lorenzo,” Coppola tells Deadline, “He came through on the financing during a hard time for independent films and he took a little risk to help make this film.”

She further praises, “We had to start without having everything in place. He just took a lot of risk and the responsibility of getting our payroll started before we had figured out our environment. He came through so we could start shooting in our small window.”

Coppola cites that while costs were tight, the production went over on music, but, Mieli saved the day and stretched the budget.

Guadagnino has a similar echo about Mieli and financing on Bones and All. It was Guadagnino’s first time shooting in the states, not to mention a period film “which made us a bit short of the budget.”

“We needed some more money and we got it immediately, I think it was a matter of hours,” says the director.

Penguin Random House

With details rather confined on the Jolie project, Without Blood, Mieli’s The Apartment was key in getting the production to have Cinecittà stand in for Central America. It’s one of several projects that Mieli has brought to the famed Rome studio lot, home of Fellini, after Guadagnino’s Queer which used the lot for Mexico, and Wright’s M. for early 20th century Milan where the offices of the Socialist Party newspaper that Mussolini edited, Avanti! resided. Without Blood was greenlight under Jolie’s overall deal with Fremantle.

Without Blood follows Nina who hunts down the killers who took out her father during wartime. Given how Mieli doesn’t have a heavy hand in the editing room, he says his style with each filmmaker is different from filmmaker to filmmaker in regards to when he steps in.

“With Luca, he wants me to go into the editing room now, he likes to have me in the process while Paolo, for example, I watch the director’s cut, then we start talking. Then there’s a back and forth.” With Coppola and Jolie, Mieli stepped into the editing suite after their respective first assembly cuts.

“He taught me a big lesson,” compliments Guadagnino about Mieli’s editing touch, “You don’t need to get the character to walk a lot of steps in order to give a sense of tempo in a movie.” The director says that with Queer he wanted a Mexico City, dreamy with colors that was “in a way staged, not real,” hence Mieli’s suggestion to recreate the location at Cinecittà.

Cinecittà becomes Mexico City in the set of Guadagnino’s ‘Queer’

Deadline

At Guadagnino’s editing suite with Costa, Mieli screens what’s essentially a sizzle reel for Queer. Costa cut it so that Mieli and Guadagnino could get a feel for the pic’s tone. However, the jazzy, frenetic footage is exciting enough to easily serve as a trailer or a pitch to buyers, should the filmmakers plan to use it. Queer is based on William Burroughs 1985 novel, but it was written between 1951 and 1953. The book is also a follow-up to the author’s Junkie. The pic follows Craig as Lee, who recounts his life in Mexico City among American expatriate college students and bar owners surviving on part-time jobs and GI Bill benefits. Lee is self-conscious, insecure and driven to pursue a young man named Allerton, who is based on Adelbert Lewis Marker (1930-1998), a recently discharged American Navy serviceman from Jacksonville, FL, who befriended Burroughs in Mexico City.

We’ve seen the 007 actor play raw before, but not like this, hallucinating, strung out, entranced by a ceiling fan and crazily popping off a gun. Images of bugs, dirty wallpaper and blood. The colors are vibrant in pinks and blues, and greys. While Costa is known to work fast (he edited Challengers in 15 days), Queer is still in need of VFX backdrops, evident in the green screens popping up in additional footage we watched. It would not be shocking to see that Italy’s next big cinema export, Queer, in the Oscar conversation next year.

Like Leone with his spaghetti westerns, Queer is another Mieli project, set abroad, about an American, but made in Italy.

“I think you should be aware of the fact that Lorenzo is a producer on the scenario of the world, not from Italy,” emphasizes Guadagnino, “Italy is just the passport.”