For all the headlines about the U.S. box office’s erosion from streaming post pandemic, Italy has it far worse.

The homeland of De Sica, Bertolucci, Leone and Fellini has seen its cinemagoing struggle well into the 1980s and 1990s. Moviegoing has always been in the big cities, not the coastal towns. Summer box office season? Nah, Italians go to the beach. While the country has always been a pit stop for Hollywood, it’s never been as vibrant a market as say UK, Germany or France. Coming out of the pandemic, there’s been a significant closing of theatrical windows and shuttering of theaters; in fact 500 cinemas were lost in 2022 two years after 3,6k theaters were closed. Box office last year in the country totaled $328M with 44.5M admissions, close to a 50% drop next to 2017-2019 levels. It’s for this reason why we see Italian Oscar submissions being exported to the U.S. via Netflix (read, Paolo Sorrentino’s 2022 International Film nominee, The Hand of God).

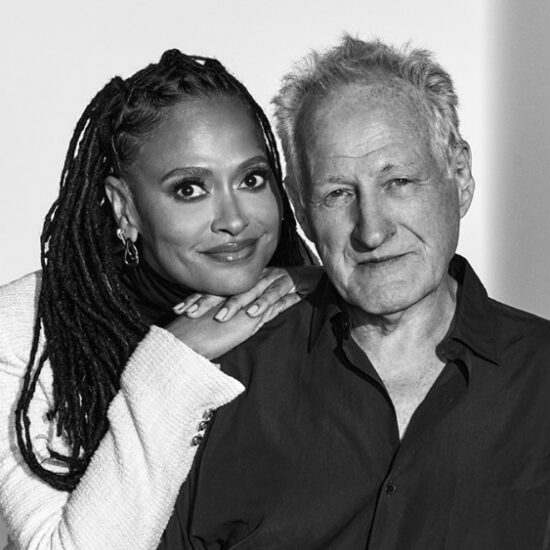

We caught up with two of this year’s Palme d’Or in the running Italian filmmakers, Alice Rohrwacher and Nanni Moretti, to chat about the state of Italian cinema. Moretti had the world premiere of A Brighter Tomorrow on Wednesday, the pic containing a swipe at Netflix and its algorithmic formula to grab audiences’ eyeballs in a pic’s first two minutes. Rohrwacher’s La Chimera makes it world premiere at Cannes this afternoon.

Moretti, for one, feels the pain personally:

“I have owned for 32 years now a cinema, and I know very well that the public is always less and less in the cinema,” says the 2001 Palme d’Or winner of The Son’s Room.

Still despite the bad news, Moretti believes that the cinema will “Keep intact. Is power, is energy, is strength.”

“In my opinion (streaming) platforms are okay for series, but for films and movies are adequate for cinema,” adds Moretti.

We’re in a time where it’s okay to be alone than with other people after this pademica,” reflects Le Pupille Oscar nominee Rohrwacher.

“(For) people, it’s very much better to see (a) movie in a collective experience. I do movies because I trust the collective experience. Maybe this is the main reason why I’m doing a movie. As part of the audience, not as director, for me it’s very important to go into a place, with people I don’t know and look all together at the same story and feel this view on this story all together, and exchange the feeling with people.”

Says Rohrwacher, “The cinema reunites the people.”