In a special series, The A.V. Club looks at the legacy of Warner Bros. 100 years after the studio was founded.

Los Angeles had already established itself as the movie-making capital of the world by 1923. Construction had just finished on the Hollywood sign (or the “Hollywoodland” sign, as it read back then), showman Sid Grauman was establishing a vital exhibition franchise with a series of elaborate movie palaces, and the big three studios—First National, Paramount Pictures, and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer—were churning out silent films by the dozens.

In the background of this burgeoning scene, four then-minor players were about to start their own Hollywood story. On April 4, 1923, immigrant brothers Harry, Sam, Albert, and Jack Warner, the proprietors of a small independent Poverty Row studio, secured an initial loan of $50,000 from a family friend and formally filed to incorporate their production company as Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc.

Over the next 100 years, the Warner Bros. journey would be filled with remarkable achievements, substantial behind-the-scenes dramas, and the kinds of twists and turns that would that rival the studio’s on-screen stories. The Warners would build one of the world’s most powerful media empires, and their studio would exert an outsized influence on popular culture, producing some of the silver screen’s most iconic films and characters. This is a look at some of the most important contributions from the storied studio, and how those developments reshaped the entertainment industry for decades to come.

G/O Media may get a commission

The Jazz Singer makes a big noise

Although Warner Bros. had a few scattered hits in the silent era, it wasn’t until 1927, when the studio ushered in the era of sound with The Jazz Singer, that the brothers staked their claim among the big boys as a force in the industry. But before the Warners could enjoy the fruits of the Al Jolson hit, they took some big financial risks on the technology that powered the sound revolution.

At the urging of Sam, the most technically adept of the brothers, the studio had laid out a healthy stack of cash to acquire the Vitaphone sound system from Western Electric. It was an expensive process, involving recording separate sound discs, which were then played on a phonograph attached to a projector.

The first major Warner Bros. feature to use this technology was 1926’s Don Juan, directed by Ernst Lubitsch and starring John Barrymore (it had synchronous music, but no dialogue). Despite selling out theaters, the production wound up losing money and almost bankrupted the young studio. Fortunately, success was just around the corner, as The Jazz Singer brought about a seismic change in film production that had the rest of the industry playing catch-up.

Warner Bros. followed up with more sound features, including Lights Of New York, The Singing Fool and The Terror. Soon the studio was making so much money with its talkies that it was able to buy a stake in First National Pictures and eventually absorb the rival studio entirely. The brothers then set their sights on the next big technological advancement: color. By the early 1930s Warner Bros. was producing all-talking, all-singing, full-color musicals like Gold Diggers Of Broadway, The Show Of Shows, Bright Lights, Song Of The Flame, and 42nd Street. Most of them were musical reviews or based on existing Broadway shows. While most people think of MGM as the studio of early, big-budget musicals, Warner Bros. nearly rivaled MGM’s output during this period (though with smaller budgets due to Jack Warner’s infamous penny pinching). They did, after all, have Busby Berkeley on contract.

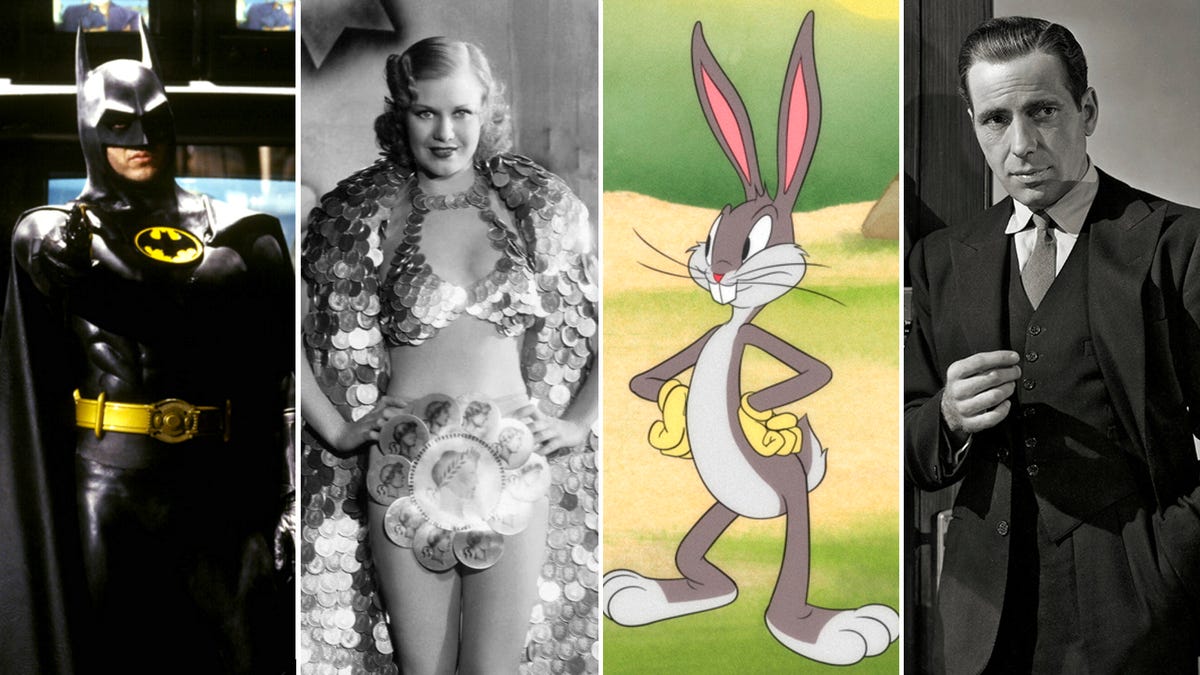

Gangsters and noir: Cagney, Bogart chart a new course

Unlike the sound revolution, which practically happened overnight, it took longer for color to become standard in the film industry. As grandiose musicals began to fall out of fashion with the public, so did color, which was closely associated with the genre. Many studios, Warner Bros. included, never gave up on black-and-white dramas and grittier fare (in part because those films were cheaper to make) and continued releasing them alongside flashier color productions well into the 1950s.

The studio was already well suited to counter-program the bright, happy-go-lucky world of those early musicals with films that were darker, more violent, and morally complex. Through the 1930s and ’40s, under head of production Daryl F. Zanuck, gangster and noir films would become the studio’s signature product. To this day these genres are an indelible part of the studio’s legacy. Films like Little Caesar, The Public Enemy, and Smart Money were early hits for Warner Bros., connecting with audiences who were fascinated by stories of the shady underworld of organized crime and bootleggers that emerged during the prohibition era (which didn’t end until 1933). They made huge stars of Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, and Paul Muni.

The impact of these films waned with the introduction of the Hays Code in 1934, which severely limited the kind of material Hollywood could include in its films, according to what industry censors considered acceptable. Warner Bros. continued to produce gangster films, though the violence and criminality was watered down to acceptable levels. Among these was The Petrified Forest, starring Leslie Howard, Bette Davis, and Humphrey Bogart, in his first leading role. Davis was a big name among Warner’s contracted stable of actors at the time, which also included Errol Flynn, Barbara Stanwyck, and Lauren Bacall. But it was Bogart—star of beloved noir classics like The Maltese Falcon, Casablanca, and The Big Sleep—who would eventually become one of the studio’s most valuable stars, and one of the most recognizable Hollywood icons of all time.

Looney Tunes: Taking animation to new heights

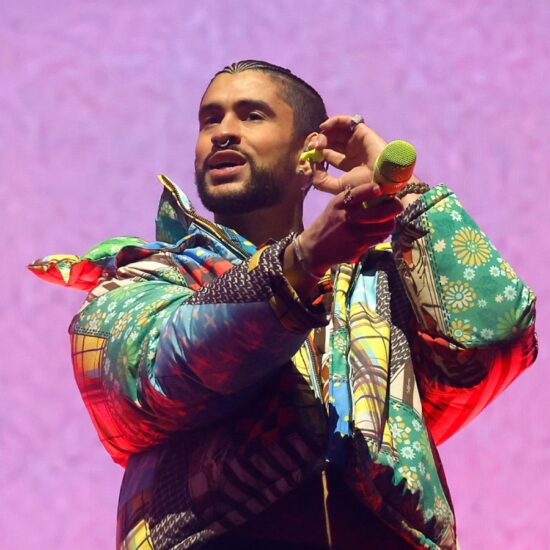

Of course, we can’t talk about Warner Bros. without mentioning another recognizable icon: Bugs Bunny. Just as Mickey Mouse is recognized as Walt Disney’s corporate mascot, Bugs stands as the spokes-bunny for Warner Bros. He didn’t start out that way, though. Warner Bros. had originally contracted an outside animation studio, Leon Schlesinger Productions, to create cartoons to play before their feature films. Schlesinger and his team produced the Merrie Melodies and Looney Tunes cartoon series from the early 1930s through 1944, when the studio officially bought out the company and renamed it Warner Bros. Cartoons.

Among the directors who started with Schlesinger and wound up working directly for Warner Bros. were familiar names like Friz Freleng, Tex Avery, and Chuck Jones. Their first breakout character was actually Porky Pig, who made his initial appearance in the 1935 short “I Haven’t Got A Hat.” He was followed by Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd, and later Bugs Bunny in “A Wild Hare,” released in 1940. By 1942, Schlesinger’s studio was more successful than even Walt Disney’s famed animation division. It’s no wonder Warner Bros. took an interest and eventually acquired it. But by most accounts, they didn’t know what they had. The early years of Bugs and company under the Warner Bros. supervision are rife with tales of neglect and budgetary limitations.

Despite these struggles, the animators kept plugging away, creating even more characters like Tweety Bird, Wile E. Coyote, and Yosemite Sam, and producing what have come to be considered artistically and historically significant works under the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies banners. By the time the animation division was shuttered in 1963 (it reopened in 1967), it had earned the studio 22 Academy Award nominations for best short subject, winning five of them. Four Looney Tunes shorts have been included on the National Film Registry: Porky In Wackyland (1938), Duck Amuck (1953), One Froggy Evening (1955), and What’s Opera, Doc? (1957). Even now, the studio continues to make the most of these characters in new shows, films, games, books, merch, theme park attractions, and more. Of all of the stars to come out of the Warner Bros. stable, Bugs Bunny might just be the biggest. He’s certainly been the most lucrative.

Superheroes in flight: Beating Marvel to the punch

Speaking of characters born of pen and ink, another big part of the Warner Bros. story is the company’s close association with DC Comics. During the late 1950s and early ’60s the studio changed hands several times, finally ending up under the ownership of the Kinney National Company in 1969. Just two years earlier, Kinney had purchased National Periodical Publications, which would later become DC Comics, bringing the studio and the publisher under the same corporate umbrella.

Both Superman (in the 1950s) and Batman (in the 1960s) had had runs on television that pre-dated the merger, but it wasn’t until 1978 that Warner Bros. would begin to take advantage of the comic-book characters under its control. Richard Donner’s Superman: The Movie, starring Christopher Reeve as the Man of Steel, brought the character to the big screen in a way no one had ever seen before.

Featuring a story by Godfather author Mario Puzo and a cameo by Don Corleone himself, Marlon Brando, the film elevated (if you’ll pardon the pun) its source material to appeal to a mainstream audience of all ages. At the time of its release, it was one of the most expensive productions in Hollywood history. The gamble paid off; Superman was a hit with audiences and critics alike, setting box-office records and making a nice profit for Warner Bros. Three Superman sequels were produced within the next decade, but there wasn’t much of a push to bring any other DC characters to the big screen. At least, not until Tim Burton came along.

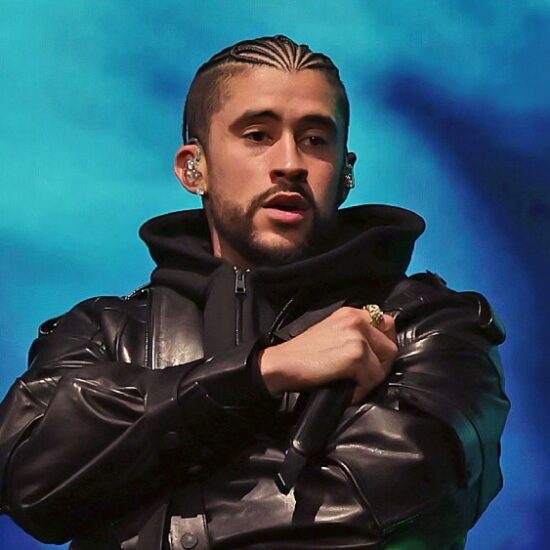

Burton’s dark, stylized take on Batman in 1989 starring Michael Keaton is credited with kicking off the modern superhero genre as we know it today. His Batmobile blazed a trail that directors like Zack Snyder and Christopher Nolan still traverse. Just like it did back in the early days of sound, Warner Bros. had a head start on its competition before the rest of the entertainment industry started to catch on that superheroes were a box-office bonanza. With Keaton once again donning the cowl in the studio’s next superhero release, The Flash, it feels like we’ve come full circle.

After all that success, facing an uncertain future

Warner Bros. may have gotten there first when it came to superheroes, but the studio long ago ceded leadership in the space to Disney’s Marvel Studios. As Warner’s DC imprint delivered consistently inconsistent results in recent years, Marvel churned out hit after hit. That situation may change with the DC arrival of former Marvel wunderkind James Gunn, who also stands to benefit from signs that Marvel’s crown may be slipping.

Of course, coming up short in the superhero sweepstakes is just one of several challenges the Warner Bros. is facing. The studio has been through its share of reinventions over the last century, but the last three decades have been especially tumultuous for the company. A series of mergers and acquisitions has seen it fall into the hands of companies like AOL, AT&T, and now Discovery, all with different visions and leadership styles. Current CEO David Zaslov has been widely criticized for his unpopular moves to cut costs, not unlike the kind of belt-tightening Jack Warner himself engaged in when he was in charge. Everyone hated him, too.

Whatever happens next for the studio, though, we’ll always have Paris, er, Casablanca. And The Jazz Singer. And A Streetcar Named Desire; A Clockwork Orange; The Exorcist; When Harry Met Sally; The Matrix; and The Dark Knight. And who knows, maybe we can add Barbie to that list soon, too.