Tucked away in the basement of a nondescript midtown Toronto government building, a group of talented international medical researchers conduct their business in secret.

Or so they like to joke.

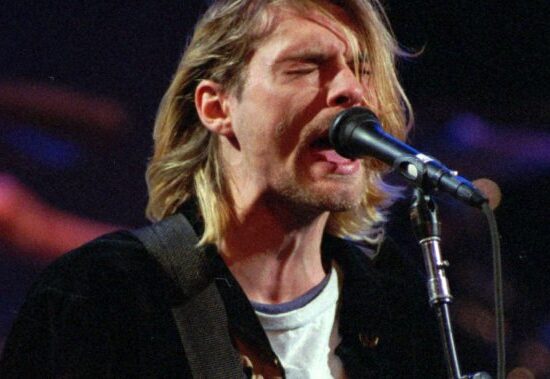

“I think we’ve been a bit shy about sharing our successes in Canada compared to at least the U.S. and a lot of sites worldwide,” Neil Vasdev, the director of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health Brain Imaging Centre, told Global News.

Notoriety aside, Vasdev and his team are doing groundbreaking work in making the connection between repetitive concussive trauma and mental health. The key, they believe, is a disorder called chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which was first discovered in the brains of deceased NFL football players. No treatment exists because thus far nobody has been able to see evidence of it in a living brain.

“Absolutely, that’s our goal,” he says. “We want to be the first centre in the world to image CTE in life.”

Dr. Neil Vasdev/Director of the CAMH Brain Health Imaging Centre.

CAMH

To get there, Vasdev has teamed up with Project Enlist, a military-focused group working under the umbrella of the Concussion Legacy Foundation. The goal of Project Enlist is to get military veterans to donate their brains. So far 250 veterans have signed up, but they need more.

Read more:

Veterans Affairs assisted dying discussion a ‘serious wake-up call,’ advocates tell MPs

Read More

“Almost all the data we have from CTE brains comes from American football players,” says Vasdev. “So we really need to see populations such as military populations.”

Tim Fleiszer, an ex-CFL star who started the foundation in 2012 says “it is an incredibly, incredibly serious issue.”

“And it’s important that we’re starting to put attention and resources towards trying to solve this problem,” he says.

The problem, as Fleiszer says, is how the medical community has historically underestimated the role of brain injuries as they relate to mental health. The U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke only recently announced a definitive link between head trauma and CTE, which doctors say can lead to depression and other mental health issues.

Fleiszer became interested in the subject at first because of his own history of being exposed to concussive trauma playing football and rugby.

He began working with concussion experts at Boston University to make life better for athletes. But when researchers in the U.S. autopsied the brains of military veterans and found almost two-thirds came back positive for CTE, he realized the scope of the problem was far greater than he initially thought.

“And what the big takeaway is, is that the brain is far more fragile than I think we realize,” says Fleiszer. “And the prevalence of these issues is far more widespread than I think we could have ever imagined.”

What they also need is funding, which now comes from a mix of the Ontario government and private donors. Fleiszer says they’ve asked the federal government for $12 million over three years and while he says Veterans Affairs has shown interest, it has yet to write a cheque.

———

Canada has more than 40,000 veterans who served during the war in Afghanistan, many of whom are now experiencing symptoms related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Ryan Carey served in the Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) after leaving the CFL. He was never wounded in battle but when he left the forces he was put on medication for operational stress injuries.

“I certainly felt like for years that nothing was working and I felt like I was following everything,” he says. “And, you know, the challenge was just more and more medication and nothing was working for me.”

He only got better when he considered all the trauma he’d inflicted on his brain, first as a football player, where he says they used to joke, “You got your bell rung, you saw stars.” And over 14 years in the military he was in countless training sessions where he was exposed to large concussive blasts.

“There’s a lot of head contact-slash-brains sloshing around in your skull,” he says.

He was able to wean off the medications when he began taking his brain health seriously by focusing on exercise, nutrition and sleep to build up his cognitive reserves.

When he became involved with Project Enlist, he learned of another RCR veteran who was travelling across the country on his motorcycle talking to veterans about PTSD.

When Michael Terry retired after 23 years in the military, like Carey, he struggled. Early in his career, he was diagnosed with PTSD, operational stress injury and major depressive disorder.

“To be completely honest, I was a mess,” he says. “The only thing I had in my life at that time was the forces. But I couldn’t stay in the forces any longer. I had to leave. And I was really probably on the verge of suicide.”

Getting out on the road likely saved his life. This past summer he travelled 33,000 kilometres and met with 620 veterans to talk about PTSD, which he documented online in a post called Dispatches. But before he spoke with Carey, he says he hadn’t considered the bigger picture, that his symptoms could be the result of all the training he’d done over the years.

Veteran Michael Terry rode his motorcycle 33-thousand kilometres across Canada in 2022.

Michael Terry

“I said, ‘You know, Ryan, I’m a PTSD guy,’” he says. “I don’t have a brain injury…. I said those famous words: ‘I’ve never had a concussion. Why do you keep talking to me about this?’”

He may not have suffered a concussion but for years Terry served as an instructor on the firing range, where he taught soldiers how to properly use the Carl Gustaf 84-mm recoilless rifle. While his students might fire one or two of the anti-tank rounds each, as an instructor he was exposed to up to 60 detonations a session.

“It’s a lot like getting kicked in the guts, I think would be the best way to describe it,” he says. “It’s just a massive shockwave. You’re standing right there in the midst of it.”

Terry shook off the discomfort and never considered the long-term implications, much as Carey did during his years in the CFL.

“One of the big challenges is we as members of the forces, we’re taught to actively fight off discomfort, to fight through discomfort,” Terry says. “And it’s a great tool, you know, for being on operations, for being in combat. It’s not such a great tool when you’re hurting afterwards.”

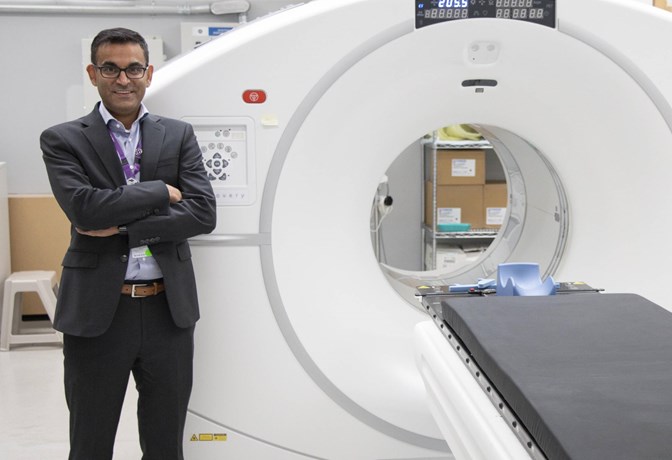

Brain Scan of Canadian soldiers showing an increase in the tau protein that could indicate presence of CTE.

Supplied by Shamantha Lora and Dr. Isabelle Boileau/CAMH Brain Imaging Centre

Vasdev says the brain can only handle so many concussive events. While they can’t definitively say they can diagnose CTE in a live brain, in unpublished images shared with Global News, researchers are able to use radioactive tracers to show a dramatic increase in tau proteins that could indicate CTE in a live brain that has more years of blast exposure.

It’s a huge, and possibly groundbreaking, step.

“We use a technique called positron emission tomography, or PET, which detects the radioactivity in specific regions of the brain,” he says. “And we can use this method to study all facets of brain health diseases.”

In the meantime, Carey and Fleiszer say they will continue to push for funding while Terry focuses on outreach, one veteran at a time.

“I worry most about the soldiers who think they’re OK, think they’re fine,” says Carey, “but they know deep down inside that they’re walking on thin ice. And any day, you know, they could fall through.”